(2) Commitment to Achieving a World without Nuclear Weapons

A) Approaches toward a world without nuclear weapons

According to the preamble of the NPT, states parties “[declare] their intention to achieve at the earliest possible date the cessation of the nuclear arms race and to undertake effective measures in the direction of nuclear disarmament, [and urge] the co-operation of all States in the attainment of this objective.” Article VI of the Treaty stipulates that “[e]ach of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effectiveinternational control.”

As mentioned in the previous Hiroshima Reports, no country, including the nuclear- armed states, openly opposes the goal of the total elimination of nuclear weapons or the vision of a world without nuclear weapons. The commitment to nuclear disarmament has been reiterated in various fora, including the NPT review process and the UN General Assembly (UNGA). However, such statements do not necessarily mean that nuclear-armed states actively pursue realization of a world without nuclear weapons. The stalemate in nuclear disarmament continued again in 2019. UN Secretary- General António Guterres expressed his sense of crisis, arguing: “Key components of the international arms control architecture are collapsing. We need a new vision for arms control in the complex international security environment of today.”6

Nuclear-armed states

For the first time since the inauguration in 2009 of regular NWS meetings on arms control, a joint statement was not adopted at the Beijing meeting in January 2019. Instead, at a press conference after the meeting, a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs simply pointed out “three important consensus” reached at the meeting, as follows.7

➢ “First, the five states pledged their shared responsibility to world peace and security. Recognizing the severe challenges to the current international security environment and the vital role of maintaining sound major country relations in resolving strategic global issues, the five countries agreed to objectively view each other’s strategic intentions, enhance exchanges in nuclear policies and strategies, strengthen mutual trust and safeguard common security.”

➢ “Second, the five states pledged to jointly uphold the NPT mechanism. They emphasized that the NPT is the cornerstone of the international nuclear non-proliferation regime and an important component of the international security architecture. They committed themselves to fully implementing the NPT comprehensively in its entirety, progressively achieving the goal of a nuclear-weapon free world, doing their utmost to resolve the nuclear non-proliferation issue through political and diplomatic means, and promoting international cooperation in peaceful use of nuclear energy.”

➢ “Third, the five states pledged to continue to make full use of their cooperation platform to maintain dialogue and coordination. They agreed to maintain strategic dialogue and strengthen coordination in the NPT review process for a successful 2020 review conference. The five countries will also actively promote open and constructive dialogues within the international community, such as the dialogue session held this morning in Beijing with internationalacademic institutions, media and embassy officials from some non- nuclear states.”

At the 2019 Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) for the NPT Review Conference (RevCon), China also delivered a statement on behalf of five NWS, and introduced the following issues as results of the NWS meeting in Beijing: “First, the P5 has started the work of the second phase of the P5 Working Group on the Glossary of Key Nuclear Terms. Second, the P5 renewed engagement with the ASEAN countries on the Protocol to the Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty. Third, the P5 actively engaged with non- nuclear-weapon states. Fourth, the P5 actively strove to strengthen the NPT regime. Fifth, the P5 convened the second Principals Meeting in the Chinese Mission in New York.” It also told five points on the NWS’s next steps of cooperation agreed by consensus at the Principals Meeting: to conduct experts- level consultations to explore the possibility of explaining respective nuclear policy and doctrine through jointly holding a side event during the 2020 RevCon; to renew engagement with the ASEAN countries on the Protocol to the Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty; to support China’s leadership on the Glossary of Key Nuclear Terms to be submitted to the 2020 NPT RevCon; to explore the way to strengthen cooperation on the peaceful use of nuclear energy, nuclear security and nuclear safety; and to push for substantive discussions on FMCT-related technical issues in the CD.”8

At the 2019 NPT PrepCom, each NWS reiterated its commitment to nuclear disarmament under Article VI of the NPT. For instance, in its working paper submitted to the PrepCom, China argued, “[R]elevant measures should follow the principles of ‘maintaining global strategic stability’ and ‘undiminished security for all.’ Countries possessing the largest nuclear arsenals bear special and primary responsibility for nuclear disarmament and should continue to make drastic and substantive reductions in their nuclear arsenals in a verifiable, irreversible and legally binding manner while faithfully implementing their existing nuclear arms reduction treaties. This would create necessary conditions for other nuclear-weapon states to join in multilateral negotiations on nuclear disarmament.”9

Russia and the United States emphasized that they had reduced their nuclear forces by more than 85% since the height of

the Cold War, and complied with their nuclear disarmament obligations under the NPT. Russia also argued that “nuclear disarmament efforts must [be] carried out incrementally…through practical measures,” and should not have a negative impact on strategic stability. In addition, it insisted: “Attempts to compel the nuclear-weapon States to give up their stockpiles unconditionally, without taking into consideration their strategic realities and legitimate security interests, are counterproductive.”10 Furthermore, Russia criticized the United States, saying, for instance, “We must vigorously oppose attempts to weaken the decades- old disarmament architecture”—bearing in mind the US withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty; and “The international community should give priority attention to the destabilizing impact of unilateral and unfettered actions of the United States of America to develop and deploy its global missile defence system.”11 At the UNGA in 2019, Russia proposed a resolution, titled “Strengthening and developing the system of arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation treaties and agreements,” which was adopted with 179 votes in favor, including the United States, and three abstentions (Ukraine, Georgia and Palau).12

In the meantime, while stressing the U.S. commitment to nuclear disarmament, including its initiative to launch the“International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification (IPNDV),” Assistant Secretary of State Christopher Ford made a negative comment regarding the ‘three pillars” of the NPT, stating at the hearing in the U.K. parliament: “[The] ‘three pillars’ formulation…is not intrinsic to the [NPT] or part of its original understanding…[T]he conceptual and structural core of the NPT is nonproliferation, and this is the foundation upon which rest the two supported ‘structures’ of nuclear disarmament and peaceful uses.”13

Among the other nuclear-armed states outside the NPT, India, at the First Committee of the UNGA, introduced its approach that seemed to merge those of both nuclear-weapon states and non- aligned (NAM) states, stating that “the goal of nuclear disarmament can be achieved in a time-bound manner by a step-by-step process underwritten by a universal commitment and an agreed multilateral framework that is global and non-discriminatory.”14 Pakistan “reiterate[d its] commitment to the goal of a nuclear weapons free world that is achieved in a universal, verifiable and non-discriminatory manner,” and argued: “Nuclear disarmament…needs to be pursued in a comprehensive and holistic manner.”15 The Prime Minister of Pakistan also told that Pakistan would renounce nuclear weapons if India did so. 16

Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND)

One of the approaches to nuclear disarmament that drew attention in 2019 was the “Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND)”— renamed from the “Creating Condition for Nuclear Disarmament (CCND)” proposed at the 2018 NPT PrepCom 17 — advocated by the United States, which argues that the international security environment needs to be improved for promoting nuclear disarmament. At the 2019 NPT PrepCom, the United States stated: “[W]e are developing a new dialogue exploring ways to ameliorate conditions in the security environment that impede progress toward a future safely and sustainably free of nuclear weapons…Since the favorable conditions that made that progress possible no longer apply, it is time to build a new disarmament discourse that can help meet these challenges.”18 Washington also announced to host the CEND Working Group (CEWG) and hold a kick-off plenary meeting. According to the United States, the objectives of the meeting were: to make concrete progress in identifying and addressing the factors in the international security environment that inhibit prospects for further progress in disarmament; and to establish a more pragmatic approach to disarmament that can contribute to a successful outcome at 2020 RevCon. The United States also pointed out the focuses of discussions, which include: measures to modify the security environment to reduce incentives for states to retain, acquire, or increase their holdings of nuclear weapons; institutions and processes nuclear and non-nuclear weapons states can put in place to bolster non-proliferation efforts and build confidence in nuclear disarmament; and interim measures to reduce the likelihood of war among nuclear-armed states. 19

The first CEWG plenary meeting was held on July 2-3, with 42 countries participating (including five NWS, non- NPT signatories, U.S. allies, and proponents of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)). 20 While the U.S. Government did not reveal the outcome of the meeting, participants discussed the above three topics. 21 In November, Working Group meeting was held in the United Kingdom, which 31 countries attended to discuss the same issues.22

Some of the NAM countries criticized the U.S. proposal on the CEND. Iran, for instance, argued: “During the 2020 Review Conference, we should strongly reject such U.S. concepts as the CCND that aims to create conditionality for nuclear disarmament obligations under article VI and to reinterpret its provisions as well as the nuclear disarmament related obligations agreed upon at the previous [NPT RevCons]. We must vigorously follow our own CCND: Comprehensive Convention on Nuclear Disarmament.”23

NNWS

As for approaches to nuclear disarmament, while the five NWS have argued for a step-by-step approach, NNWS allied with the United States have proposed a “progressive approach” based on building-block principles, and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) countries have called for launching negotiations on a phased program for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons within a specified time frame.

At the 2019 NPT PrepCom, the New Agenda Coalition (NAC: Brazil, Egypt, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand and SouthAfrica) reiterated that “all States parties should be held fully accountable with respect to strict compliance with theirobligations under the [NPT],” including article VI. It also proposed, inter alia, that, at the 2020 NPT RevCon, the states parties would discuss nuclear risk and humanitarian consequences, and global security environment and nuclear disarmament; as a starting point, reiterate the continuing validity of all commitments and undertakings entered into at the past RevCon; reiterate the nuclear disarmament principles of irreversibility, verifiability and transparency and call for their adequateapplication; and reaffirm that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”24

The NAM countries once again argued “the urgent necessity of negotiating and bringing to a conclusion a phased programme for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons with a specified time frame,”25 and proposed concrete measures be taken toward an elimination of nuclear weapons, with dividing in three phases during 2020-2035. 26

Japan stated as follows:27

As the only country to have ever suffered atomic bombings during war, Japan has a deep understanding of the catastrophic consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. I would like to take this opportunity to express my respect for the tireless efforts of the Hibakusha, the atomic bomb survivors, who have conveyed the reality of the atomic bombings to the world in pursuit of the elimination of nuclear weapons.

On the other hand, it is also the solemn responsibility of a sovereign state to protect the lives and property of its people. Japan strives to advance nuclear disarmament and security simultaneously, taking into account both humanitarian and security considerations.

We are currently witnessing a deteriorating security environment, a divergence of views on disarmament, and the growing threat of the proliferation of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction. Against this backdrop, we must reassume realistic measures with the cooperation of both nuclear-weapon States and non-nuclear-weapon States.

At the 2019 NPT PrepCom, Japan also introduced the “the Group of Eminent Persons for Substantive Advancement of Nuclear Weapons” submitted the “Kyoto Appeal,” which recommended 13 items and emphasized that rebuilding civility and respect in discourse and restoring practices of cooperation on nuclear arms control and threat reduction are required as a solid foundation for a more stable, safe, and prosperous world.

Stepping-stone approach

In addition to the CEND, another proposal that attracted attention in 2019 was Sweden’s “Stepping-stone approach.” In its working paper submitted to the 2019 NPT PrepCom, Sweden stated: “The situation is too dangerous for the future stability of the international community, hence the need for ‘actionable’ implementation measures…[and the] ‘stepping stone’ approach…offers a process to build political support for pragmatic, short- term, achievable demonstrations of commitment to the global disarmament regime.” It also listed concrete measures as “stepping stones” under the four principles of reducing the salience of nuclear weapons; rebuilding habits of cooperation in the international community; reducing nuclear risks; and taking steps to enhance transparency on arsenal size, control fissile materials and nuclear technology. For instance, Sweden recommended the following measures for reducing nuclear risks: improving crisis communication channels and protocol; creating a clear distinction between conventional and nuclear delivery systems; command and control vulnerabilities to cyber threats; codifying existing non-deployment arrangements for non-strategic nuclear warheads; considering measures aimed at extending decision-times in crisis.29

In June 2019, Sweden hosted the “Stockholm Meeting on Nuclear Disarmament and the NPT.” The meeting was attended by 16 NNWS,30 and a joint declaration toward the 2020 NPT RevCon was adopted, stating the following points, inter alia:31

➢ “A potential nuclear arms race – which would serve no one’s interest – must be avoided.”

➢ “Contributing to such efforts will be our focus in the year ahead. Our approach will be ambitious yet realistic. We seek in 2020 an outcome that reaffirms the role of the NPT as the cornerstone of the global disarmament and non- proliferation regime. It should give real meaning to this by identifying stepping stones for the implementation of Article VI of the Treaty, building on the commitments made during a series of Review Conferences, notably in 1995, 2000 and 2010.”

➢ “Recognizing the highly challenging character of the global security environment, our discussions today covered a wide range of issues, including more transparent and responsible declaratory policies, measures to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in doctrines and policies, ways of enhancing transparency and of reducing risks of any use of nuclear weapons, strengthened negative security assurances, work on nuclear disarmament verification and the importance of addressing the production of fissile material.”

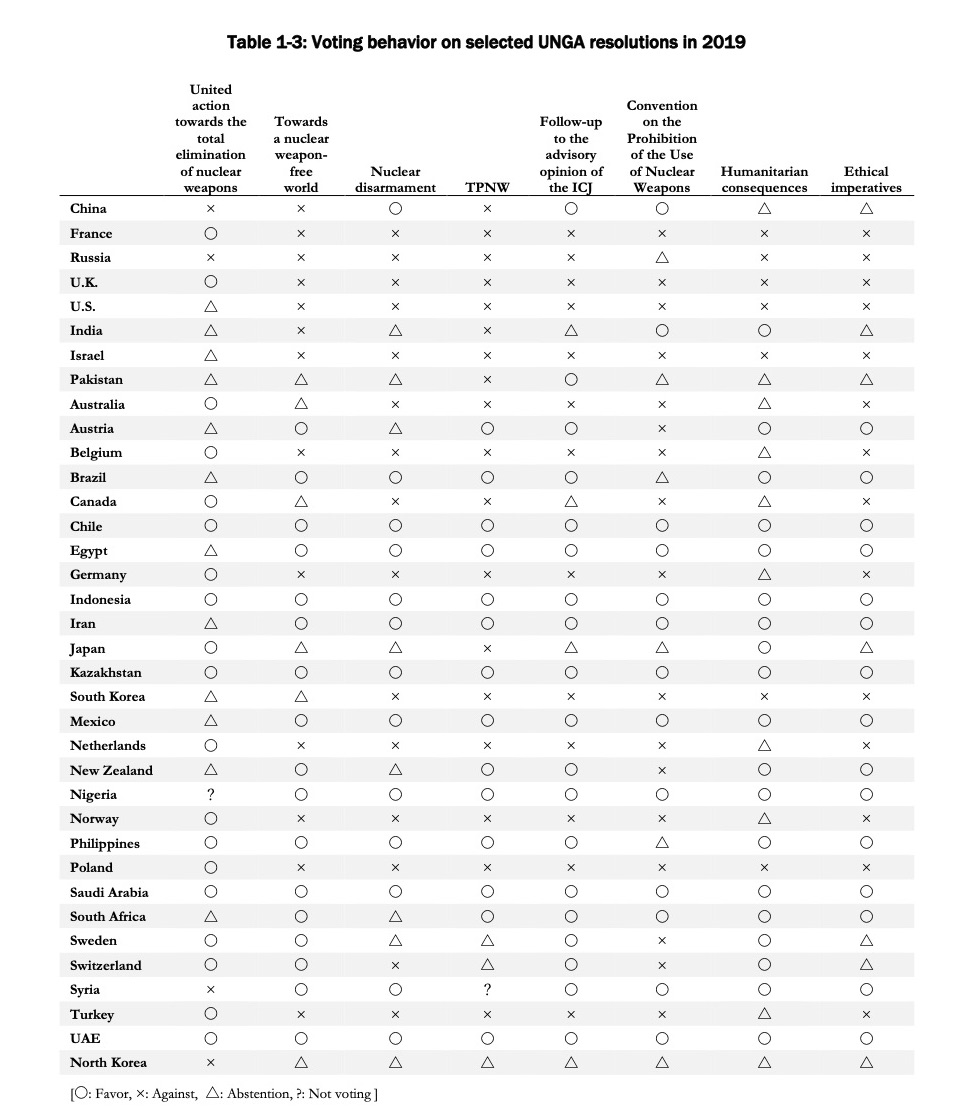

B) Voting behavior on UNGA resolutions on nuclear disarmament proposals by Japan, NAC and NAM

In 2019, the UNGA again adopted resolutions titled: “Joint courses of action and future-oriented dialogue towards a world without nuclear weapons”32 proposed by Japan and others; “Towards a nuclear-weapon-free world: accelerating the implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments”33 proposed by the New Agenda Coalition (NAC); and “Nuclear disarmament”34 by NAM members. The voting behavior of the countries surveyed in this project on the three resolutions at the UNGA in 2019 is presented below.

➢ Joint courses of action and future- oriented dialogue towards a world without nuclear weapons

Proposing: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Sweden, UAE, the United Kingdom and others

160 in favor (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Netherlands, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UAE, the United Kingdom and others), 4 against (China, North Korea, Russia and Syria), 21 abstentions (Austria, Brazil, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, South Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, the United States and others) – Nigeria did not vote

➢ Towards a nuclear-weapon-free world: accelerating the implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments”

Proposing: Austria, Brazil, Egypt, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, South Africa and others

137 in favor (Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, UAE and others), 33 against (Belgium, China, France, Germany, India, Israel, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and others), 16 abstentions (Australia, Canada, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, Pakistan, and others)

➢ Nuclear disarmament

Proposing: Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Philippines and others

120 in favor (Brazil, Chile, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Nigeria, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Syria, UAE and others), 41 against (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Israel, South Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and others), 22 abstentions (Austria, India, Japan, North Korea, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sweden and others)

The title of the resolution proposed by Japan was changed from previous year’s “United action with renewed determination towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons.” Compared with the previous one, the

resolution in 2019 was simplified: proposed “guidelines for joint action” listed measures that could be taken in a relatively short period of time, such as improving transparency and confidence- building by NWS, reducing nuclear risks, declaring a moratorium on the production of weapons-grade fissile materials, signing and ratifying the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), contributing to nuclear disarmament verification, and promoting disarmament and non-proliferation education. The resolution also called for “future oriented dialogues” since “various approaches exist towards the realization of a world without nuclear weapons and that confidence-building among all States is essential to this end.”

Among the NWS, France (which had abstained last year) and the United Kingdom voted this resolution in favor, while the United States35 abstained and China36 and Russia opposed it.

In addition, some NNWS, including those promoting the TPNW, abstained, arguing that the resolution reaffirmed only some of the nuclear disarmament issues and implied an intention to step back from agreements made at the past NPT RevCons. New Zealand, for example, expressed strong dissatisfaction in its explanation of vote: “My Delegation had hoped that Japan’s decision this year not to present its earlier resolution…signalled a move away from the divisive approach toward nuclear disarmament which that text had encapsulated. We are sorry to see that this is not the case.”37 Mexico also said: “[T]he language used in some of the paragraphs reinterprets previous agreements adopted within the Non- Proliferation Treaty, especially provisions stemming from article VI.”38 Furthermore, the resolution was criticized because, among others, it did not mention the U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control treaty or the TPNW; and it deleted the expression “deep concern” regarding the humanitarian dimension of nuclear weapons.39

C) Humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons

Since the 2015 NPT RevCon, the Humanitarian Group, which focuses on the humanitarian dimensions of nuclear weapons, has emphasized the significance of starting negotiations of a legally binding instrument on prohibiting nuclear weapons. The result was the adoption of the TPNW in 2017.

The Humanitarian Group submitted working papers on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons at the 2019 NPT PrepCom. In its working paper, the Humanitarian Group— including Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, the Philippines and South Africa—as it did in the working paper submitted to the 2018 NPT PrepCom, reaffirmed its commitment to further enhance awareness of humanitarian impact; called on NWS to take concrete interim measures with urgency to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons detonation; and expressed its recognition that new evidence regarding the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons lends further strength to the view that these weapons cannot be used in conformity with international law, and that the risk of nuclear weapons’ use can be avoided only through the total elimination of nuclear weapons and maintenance of a world free of nuclear weapons.40

On the other hand, NWS were not favorable to humanitarian issues in nuclear disarmament. While the United Kingdom and the United States attended the Third International Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, NWS kept their distance from these issues especially when the Humanitarian Group began to officially pursue a legal prohibition of nuclear weapons. For example, NWS has not used the term “humanitarian” in their documents submitted to the NPT RevCon and its PrepComs.

The UNGA resolutions on nuclear disarmament led by Japan in 2017 and 2018 were criticized by some NNWS, including the Humanitarian Group, and civil society the removal of the word “any” in the resolutions phrasing, which in 2016 read: “[e]xpressing deep concern at the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons.” They called the removal an unacceptable step backward. In addition, the sentence, “deep concerns about the humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons continue to be a key factor that underpins efforts by all States towards a world free of nuclearweapons,” which had been written in the 2018 resolution, was not included in the 2019 resolution.

At the 2019 UNGA, the Humanitarian Group, as in the previous year, proposed a resolution titled “Humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons.”41

The voting behavior of countries surveyed in this project on this resolution is presented below.

➢ Proposing: Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland and others

➢ 144 in favor (Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, UAE and others), 13 against (France, Israel, South Korea, Poland, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States and others), 28 abstentions (Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Germany, North Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Turkey and others)

Furthermore, the voting behavior of the resolution titled “Ethical imperatives for a nuclear-weapon-free world”42 led by South Africa was:

➢ Proposing: Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Philippines, South Africa and others

➢ 135 in favor (Austria, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Syria, UAE and others), 37 against (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Israel, South Korea, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and others), 13 abstentions (China, India, Japan, North Korea, Pakistan, Sweden, Switzerland and others)

6 “UN: Global Arms Control Architecture ‘Collapsing,’” AFP, February 25, 2019, https://www. voanews.com/europe/un-global-arms-control-architecture-collapsing.

7 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang’s Regular Press Conference,” January 31, 2019, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/ t1634507.shtml.

8 “Statement by China, on Be half of the P5 States,” General Debate, the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2020 NPT Review Conference (2019 NPT PrepCom), May 1, 2019.

9 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.40, April 26, 2019.

10 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.6, March 15, 2019.

11 Ibid.

12 A/RES/74/66, December 12, 2019.

13 Christopher Ford, “The Structure and Future of the Nuclear Non proliferation Treaty,” International Relations Committee, House of Lord, December 12, 2018, https://www.parliament.uk/documents/lords- committees/International-Relations-Committee/foreign-policy-in-a-changing-world/Dr-Christopher- Ford-Assistant-Secretary-Bureau-International-Security-Nonproliferation-US-StateDept.pdf.

14 “Statement by India,” First Committee, UNGA, October 22, 2019.

15 “Statement by Pakistan,” First Committee, General Debate, UNGA, October 16, 2019.

16 “Nuclear War is not an Option; Pakistan Would Give Up its Weapons, If India Did :Imran Khan,”APP, July 23 2019, https://www.app.com.pk/nuclear-war-is-not-an-option-pakistan-would-give-up-its-wea pons-if-india-did-imran-khan/.

17 William Potter argued that this renaming was in response to criticisms from many NNWS which regarded “conditions” as implying “conditionality” of nuclear disarmament. See William C. Potter, “Taking the Pulse at the Inaugural Meeting of the CEND Initiative,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, July 15, 2019, https://www.nonproliferation.org/taking-the-pulse-at-the-inaugural-meeting-of- the-cend-initiative/

18 “Statement by the United States,” General Debate, 2019 NPT PrepCom, April 29, 2019.

19 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.43, April 26, 2019.

20 According to the following article, the names of 42 countries—including Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the UAE, the United Kingdom, and the United States—were listed as participants. See Potter, “Taking the Pulse at the Inaugural Meeting of the CEND Initiative.”

21 Regarding the first meeting, see Ibid.; Shannon Bugos, “U.S. Hosts Nuclear Disarmament Working Group,” Arms Control Today, Vol. 49, No. 7 (September 2019), p. 37. Moderators for three groups were served by experts belonging to private think tanks.

22 See Christopher Ashley Ford, Assistant Secretary Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, “Moving Forward with the CEND Initiative,” Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND) Working Group, Wilton Park, United Kingdom, November 20, 2019, https://www. state.gov/moving-forward-with-the-cend-initiative/.

23 “Statement by Iran,” Cluster 1, 2019 NPT PrepCom, May 2, 2019. Some NNWS, including U.S. allies, concern that, through the CEDN, the United States might attempt to step away from measures and commitments on nuclear disarmament agreed by the states parties to the NPT at its RevCon. See, for instance, Lyndon Burford, Oliver Meier and Nick Ritchie, “Sidetrack or Kickstart? How to Respond to the US Proposal on Nuclear Disarmament,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, April 19, 2019, https:// thebulletin.org/2019/04/sidetrack-or-kickstart-how-to-respond-to-the-us-proposal-on-nuclear- disarmament/; Paul Meyer, “Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament: Striding Forward or Stepping Back?” Arms Control Today, April 2019, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2019-04/features/ creating-environment-nuclear-disarmament-striding-forward-stepping-back.

24 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.35, April 26, 2019.

25 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.12, March 21, 2019

26 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.10, March 21, 2019

27 “Statement by Japan,” General Debate, 2019 NPT PrepCom, April 29, 2019.

28 Ibid.

29 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP33, April 25, 2019.

30 Argentina, Canada, Ethiopia, Finland Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden (Chair) and Switzerland.

31 “Ministerial Declaration,” The Stockholm Ministerial Meeting on Nuclear Disarmament and the Non- Proliferation Treaty, June 11, 2019, https://www.government.se/statements/2019/06/the-stockholm- ministerial-meeting-on-nuclear-disarmament-and-the-non-proliferation-treaty/.

32 A/RES/74/63, December 12, 2019.

33 A/RES/74/46, December 12, 2019.

34 A/RES/74/45, December 12, 2019.

35 The United States explained: “While we could not support a number of elements in L.47, we want to take this opportunity to thank Japan for streamlining the text and refocusing it on the future. We also note with satisfaction that L.47, perhaps unique in any resolution before this Committee, encourages states toconduct a candid dialogue on the relationship between nuclear disarmament and security.” John Bravaco, Acting Head of U.S. Delegation, “Explanation of Vote, After the Vote on L.47, ‘Joint Courses of Action and Future-oriented Dialogue towards a world without nuclear weapons,’” First Committee, UNGA, November 4, 2019.

36 China “rejected the idea of visiting areas of nuclear bombings, even though he expressed sympathy for the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, adding that ‘learning from history and how to prevent tragedy is more important than an invitation to visit.’” United Nations, “First Committee Sends 19 Resolutions, Decisions to General Assembly, Issuing Strong Calls for Clearing Path towards Nuclear-Weapon-Free World,” Meeting Coverage, November 1, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gadis3640.doc.htm.

37 New Zealand, “Explanation of Vote on L.47,” November 4, 2019.

38 United Nations, “First Committee Sends 19 Resolutions, Decisions to General Assembly, Issuing Strong Calls for Clearing Path towards Nuclear-Weapon-Free World,” Meeting Coverage, November 1, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gadis3640.doc.htm.

39 See, for instance, Akira Kawasaki, “Encouraging to Dismiss the Agreements and Weakening the Expression Regarding Humanitarian Dimensions: Problems with Japan’s Draft UN Resolution on Nuclear Disarmament,” October 25, 2019, https://kawasakiakira.net/2019/10/25/2019ungajapanres/. (in Japanese)

40 NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.44, April 26, 2019.

41 A/RES/74/42, December 12, 2019.

42 A/RES/74/47, December 12, 2019.