Hiroshima Report 2023(5) Reduction of Nuclear Weapons

A) Reduction of nuclear weapons

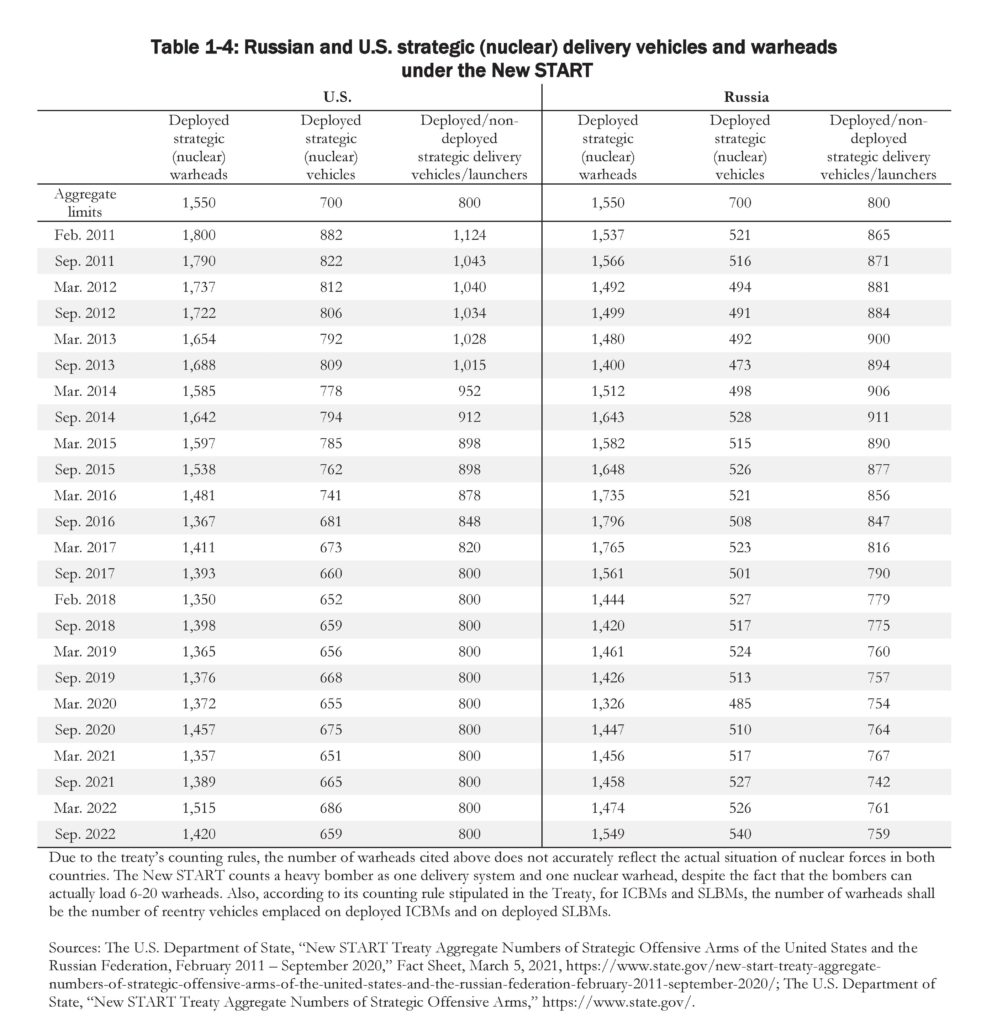

As of 2022, the United States and Russia have implemented reductions in nuclear weapons under the New START,80 which was extended for five years in February 2021.

The status of their strategic (nuclear) delivery vehicles and warheads under New START has been periodically updated on the U.S. Department of State homepage (see Table 1 1-4). 81 According to the data as of February 5, 2018 —the deadline for reducing their strategic arsenals under the treaty—the number of Russian and U.S. deployed strategic delivery vehicles and deployed/ non-deployed strategic delivery vehicles/launchers, besides deployed strategic warheads, fell below the limit.

They continue to meet the limits for strategic nuclear forces.

Since the treaty’s entry into force, Russia and the United States have implemented on -site inspections under the New START. However, these inspections have not been conducted since April 1, 2020.

This was originally due to the global pandemic of COVID-19 which made it difficult for inspectors to enter each other’s countries. However, in August 2022, Russia announced that it would temporarily suspend its acceptance of on-site inspections from the U.S. side under New START , claiming that the conditions proposed by the United States would bring unilateral benefits to it and effectively deprive Russia of the right to conduct on -site inspections on U.S. territory, and that on-site inspections by Russia in U . territory have become virtually impossible, since Russian air traffic to the United States has been suspended due to sanctions by Western countries following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia also emphasized that this measure was “temporary,” and called on the United States to lift the sanctions, saying that the exemption would be suspended as soon as the issue is resolved. 82

On the other hand, U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price rebutted Russia’s argument: “ U.S. sanctions and restrictive measures imposed as a result of Russia’s war against Ukraine are fully compatible with the New START Treaty. They don’t prevent Russian inspectors from conducting treaty inspections in the United States. And we’ll continue to engage Russia on the resumption of inspections through diplomatic channels.”83 Another spokesperson later added, “ The United States has and will continue to engage Russia on the resumption of inspections through diplomatic channels,” such as the Bilateral Consultative Commission established by the treaty to address implementation and verification concerns. ”84

Russia’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said on September 29 that Russia was considering the possibility of in-person meetings of a joint commission of representatives from the United States and Russia. 85 U.S. State Department spokesperson Price also stated on November 8 that the United States and Russia had agreed to convene a Bilateral Consultation Committee (BCC) in the near future, and that the United States “ made clear to Russia that measures imposed as a result of Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine don’t prevent Russian inspections… from conducting New START Treaty inspections in the United States. ”86 The BCC is required by treaty to be held twice a year, but they have not met since October 2021. On November 11, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said that a meeting with the U.S. side to discuss the resumption of mutual inspections under the New START would be held in Cairo later that month or early December.

However, Russia informed the United States of the postponement of the BCC, which was scheduled to begin on November 29. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov criticized the United States for attempting to focus on the issue of resuming inspections, even though Russia had asked for a discussion of broader issues such as strategic stability , and said, “We have encountered a situation where our American colleagues not only demonstrated a lack of desire to take note of our signals, acknowledge our priorities, but also acted in the opposite way.” 87 The U.S.

Department of State stated, “ The United States is ready to reschedule at the earliest possible date as resuming inspections is a priority for sustaining the treaty as an instrument of stability.” 88 However, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov said, “We are not targeting the end of the year.

It is too early to say how and when we will come up with these new proposals and what period of time we will ultimately target.” 89 The BCC could be re-convened in 2022 .

Meanwhile, the United States and Russia continued to exchange notifications under the treaty regarding the number, location, and technical characteristics of weapons systems and facilities According to the U.S. State Department, as of February 1, 2023 , the two countries have exchanged 25, 331 notifications from the entry into force of New START through the end of January 2022.90

B) A concrete plan for further reduction of nuclear weapons

In 2022 , there was no new proposal by nuclear-armed states to take concrete measures for further reductions of their nuclear arsenals. When Washington and Moscow agreed to a five-year extension of the New START in February 2021, U.S. Secretary of State Blinken said, “The United States will use the time provided by a five-year extension of the New START Treaty to pursue with the Russian Federation, in consultation with Congress and U.S. allies and partners, arms control that addresses all of its nuclear weapons.

We will also pursue arms control to reduce the dangers from China’s modern and growing nuclear arsenal. ”91 President Biden also stated in his message for the NPT RevCon, “ Today, my Administration is ready to expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START when it expires in 2026. But negotiation requires a willing partner operating in good faith. … Russia should demonstrate that it is ready to resume work on nuclear arms control with the United States. ”92 In 2022, however, little progress was made toward further nuclear arms reductions and the situation was further complicated by the intensification of strategic competition following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In June 2021, the United States and Russia agreed to launch a bilateral Strategic Stability Dialogue to seek to lay the groundwork for future arms control and risk reduction measures. At the third Dialogue , held in Geneva in January 2022, their discussions focused mainly on the increasingly tense situation in Ukraine. At the Dialogue , the United States rejected Russia’s demand for providing a guarantee of NATO’s non-extension eastward , stating that We will not allow anyone to slam closed NATO’s ‘Open Door ’ policy .” The United States also argued that no decision on those matters would be made without the countries, regions or alliances involved. 93

The United States reportedly proposed in a document dated February 1 to Russia that the United States would be willing to discuss transparency measures to confirm the absence of Tomahawk cruise missiles at Aegis Ashore sites in Romania and Poland if Russia provide provided transparency measures regarding two Russian ground-based missile bases of the U.S. choice.

The United States also proposed an early initiation of discussions on an arms control agreement following New START, which would cover new types of intercontinental-class nuclear delivery vehicles , and negotiations on future arms control agreements that encompass all U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons, including non-strategic nuclear weapons. 94

On February 17, Russia responded to the aboveabove-mentioned U.S. proposal, giving some appraisal to , inter alia, the “transparency measures,” and insisted that not just nuclear weapons but also missile defense issues should be included in an arms control framework, on the basis that: “ Russia continues to advocate an integrated approach to strategic issues.

It proposes the joint development of a new ‘security equation Russia also urged the United States to remove its nuclear weapons deployed abroad and to not deploy nuclear weapons abroad, stating that until these requirements were implemented, the topic of non-strategic nuclear weapons could not be discussed. In addition, Russia reiterated its proposal to impose a mutually verifiable moratorium on the deployment of ground-launched intermediate missiles in Europe. 95

However, following Russia’s launch of an attack on Ukraine on February 24, the United States decided to suspend the Strategic Stability Dialogue. In response, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov clarified Moscow’s position that proposals on security guarantees which Russia had sent to the United States and NATO before the war in February were no longer valid while it remained prepared to resume dialogue on arms control with the United States. 96 In April 2022, Vladimir Yermakov, director of the Russian foreign ministry’s department for non-proliferation and arms control, also said, “As of now, the situation indicates that there can be no talk at present about any prospects of talks with the United States on strategic stability. Unfortunately, all of Washington’s actions are taken in the diametrically opposite direction. … this dialogue is formally frozen by the American side.”97

In the draft final document of the NPT RevCon , the United States and Russia were called upon to commit to the full implementation of the New START and to pursue negotiations in good faith on its successor framework before its expiration in 2026, in order to achieve deeper, irreversible and verifiable reductions in their nuclear arsenals. However, no such negotiation was initiated in 2022.

Little progress was also made on nuclear weapons reductions outside of the United States and Russia. While it is not necessarily focused on nuclear arms reductions, President Biden stated, “China … has a responsibility as an NPT nuclear weapons state and a member of the P5 to engage in [arms control] talks that will reduce the risk of miscalculation and address destabilizing military dynamics.”98 The United States reiterated its willingness to pursue arms control talks with China.

However, China has consistently insisted that any participation on its part in the nuclear weapons reduction process would be premature. In its national reports submitted to the NPT RevCon, China reiterated its traditional arguments as follows:

The two countries possessing the largest nuclear arsenals should, in accordance with relevant United Nations General Assembly resolutions and documents, bear the special and primary responsibility for nuclear disarmament and continue to make drastic and substantive reductions in their nuclear arsenals in a verifiable, irreversible and legally binding manner, so as to create the necessary conditions for general and complete nuclear disarmament. When conditions permit, all nuclear-weapon States should join the multilateral nuclear disarmament process. 99

Russia also repeated its assertion that since France and the United Kingdom possess nuclear weapons that are not restricted by any international agreements, their participation in future arms control dialogues is a priority. As for non-strategic nuclear forces, Russia simply reiterated its usual explanation that it has reduced its non-strategic nuclear forces by three-quarters since 1991.

Meanwhile, France and the United Kingdom have not changed their position that the U nited States and Russia must first make further drastic reductions in their nuclear arsenals before the commencement of a multilateral nuclear arms reduction process.

The final draft of the final document of the NPT RevCon called upon the NWS for taking a following activities: “ In implementing their unequivocal undertaking to accomplish the total elimination of their nuclear arsenals leading to nuclear disarmament, the nuclear weapon States commit to taking every effort to further decrease the global stockpile of nuclear weapons and are called upon to pursue immediate reductions or further reductions in all types of nuclear weapons, regardless of their location, including through bilateral, and multilateral measures and unilateral initiatives, consistent with Action 5 of the conclusions and recommendations for follow-on actions agreed by the 2010 Review Conference. ” The draft report of Main Committee I and the first draft of a final document contained the following sentence, which was later deleted: “The nuclear-weapon States commit to pursue immediate reductions or further reductions in all types of nuclear weapons, including through bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral negotiations and unilateral initiatives.” In the meantime, the following sentence was inserted in the second revised draft: “The nuclear-weapon States acknowledge the grave concerns of non-nuclear weapon States regarding the expansion of nuclear forces and qualitative improvement of nuclear forces, including the development of advanced nuclear weapons and new types of delivery systems and commit to engage in dialogue with the non-nuclear weapon States to address these concerns during the next review cycle.

C) Trends on s trengthening/ modernizing nuclear weapons capabilities

While nuclear-armed states have reiterated their commitments to promoting nuclear disarmament, they continue to modernize and/or strengthen their nuclear weapons capabilities. At the NPT RevCon, many NNWS expressed strong concerns about the trend toward modernization of nuclear forces. The draft final document stated, “The Conference notes the concern of non-nuclear weapon States at the quantitative expansion and qualitative improvement of nuclear weapons, the development of advanced new types of nuclear weapons, and the continued role of nuclear weapons in security policies, as well as at the level of transparency surrounding these activities.”

According to a report published by International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN ) in June 2022, the total amount of nuclear weapons-related expenditures (including modernization of nuclear forces) by nine nuclear-armed states in 2021 was estimated at $ 82.4 billion (increased by $10 billion from the pre vious year), of which $ 44.2 billion was spent by the United States, approximately $11.7 billion by China, and $8.6 billion by Russia. 100 According to a report by Allied Market Research, the global market for nuclear weapons and their delivery means was estim ated to surpass $126 billion within ten years, up nearly 73% from 2020 levels.101

China

China has not disclosed the status of its development and deployment of nuclear weapons . In the meantime, it stated in its national report submitted to the NPT RevCon, “ China always keeps its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security, and does not seek parity with other countries in terms of its nuclear-weapons investment, quantity or scale. China never participates in arms race in any form.”102 Fu Cong, Director General of the Arms Control Bureau of China ’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, also denied any rapid expansion of nuclear forces by China , but said that it is working to ensure that nuclear deterrence meets the minimum level required for national defense, and that China would continue to modernize its nuclear arsenal for ensuring reliability and safety of nuclear forces.103

However, there is growing concern th that China ’s aggressive nuclear weapons modernization has accelerated in recent years. For instance, President Biden stated at the UNGA in September 2022 that “China is conducting an unprecedented, concerning nuclear buildup without any transparency.”104 According to the annual report on Chinese military and security developments published in November 2022, the U.S. Department of Defense estimated that “If China continues the pace of its nuclear expansion, it will likely field a stockpile of about 1500 warheads by its 2035 timeline.” 105

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian denied the U.S. arguments, as saying, “In recent years, the US has been hyping up various versions of the “China threat” narrative simply to find a pretext for expanding its nuclear arsenal and perpetuating military predominance. The world knows well that this is a go-to tactic of the US. China’s nuclear policy is consistent and clear. We follow a self-defensive nuclear strategy. We stick to the policy of no-first-use of nuclear weapons.

We have exercised utmost restraint in developing nuclear capabilities. We have kept those capabilities at the minimum level required by national security. We are never part of any form of arms race.” 106

The main component of China’s strategic nuclear fo rces is ICBMs. For a long time, China ’s only strategic nuclear forces capable of reaching the U.S. homeland were the 20 DF-5 silo-based ICBMs which began to be deployed in 1981. However, since the latter half of the 2000s, it has introduced DF-31A/AG mobile ICBMs, DF-5B silo-based ICBMs with MIRVs that can carry three to five warheads per a missile , and DF -41 MIRVed ICBMs which can mount up to 10 warheads per a missile (while it is also considered to carry about three warheads as well as some decoys). The U.S.

Department of Defense assesses that “[China] is rapidly establishing its silo-based solid-propellant missile fields likely consisting of over 300 silos in total, which are capable of fielding both DF-31 and DF-41 class ICBMs,”107 and estimates China has respectively 100 ICBM launchers and ICBMs in its arsenal. 108

China is also strengthening its SLBM capabilities. The U.S. Defense Department assesses that China is conducting continuous at-sea deterrence patrols with its six JIN-class (Type 094) SSBNs, which are equipped to carry up to 12 JL-2 or JL-3 SLBMs. 109The JL-3 is China’s latest SLBM with a range estimated at over 10,000 km and is capable of striking the U.S. mainland from the Chinese coast. Meanwhile, China is completing its strategic nuclear triad with the H-6N strategic bomber which can carry nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missiles, and the H-6K strategic bomber which can carry nuclear-capable cruise missiles.

Regarding non-strategic nuclear forces, China maintains a high level of ground-launched short- and intermediate-range missile forces, both qualitatively and numerically. The U.S. Defense Department’s annual report on China’s military forces estimates that China has 250 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) launchers and 250 missiles, 250 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) launchers and 500 missiles, 200 short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) launchers and 600 missiles. 110

In addition to ballistic and cruise missiles, China has been actively developing hypersonic missiles. It started to deploy DF-17 hypersonic missiles in 2020. Furthermore, it was reported in October 2021 that China conducted a test of the Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS).111

France

In 2015, France announced that it possessed not more than 300 nuclear weapons, and its nuclear deterrent consists of 54 middle-range ALCMs and three sets of 16 SLBMs.112 In 2022, there was no change in this nuclear force posture.

France plans to complete development of the M51.3 SLBMs by 2025, which incorporate a new third stage for extended range and further improved accuracy. In addition, France launched a program in 2021 to develop a third-generation SSBN (SNLE 3G) to be in service by 2035, and an M51.4 SLBM to be mounted on it by the early 2040s.113 As for the successor to the air-to-surface medium-range cruise missile (ASMPT), France has begun design and development of the ASN4G (air-sol nucléaire 4ème génération), which is scheduled to enter into service around 2035.

Russia

Russia has been actively promoting the development and deployment of various types of delivery vehicles, including the replacement of nuclear forces built during the Cold War era, mainly aiming to maintain nuclear deterrence against the United States.

Regarding Russia’s strategic nuclear forces, the first test launch of the RS-28 (Sarmat) ICBM, which is considered to be the core of Russia’s future strategic nuclear capability, took place in April 2022, and hit its target after flying 6,000 km. 114 After this test, President Putin said, “The new complex has the highest tactical and technical characteristics and is capable of overcoming all modern means of anti-missile defence. It has no analogues in the world and will not have for a long time to come.”115 Russia’s Ministry of Defense announced the second test launch of the RS-28 was successfully conducted on November 18.116 In December, President Putin said that the RS-28 would be deployed in the near future.

As for its sea-based nuclear forces, the conversion to Borei-class SSBNs has begun, with three ships in service, and five more under construction. In November 2022, it was announced that the second Borei A SSBN, which will soon be deployed by the Russian Navy, successfully launched a ballistic missile as part of its final test. 117

Russia has also been active in developing “exotic” nuclear delivery systems, and there were various developments in 2022 as in the previous years. For instance, in January, Russian Deputy Defense Minister Alexey Krivoruchko said that Tsirkon sea-launched hypersonic cruise missile was at the final stage of its trials and the missile’s serial deliveries to the Navy would begin in 2022.118 It was also reported that the first regiment of strategic missile systems with the Avangard boost-glide vehicle would go on combat duty by the end of 2021, and the second regiment would assume combat alert in the Russian Strategic Missile Force by 2023. 119

In addition, Russia’s Belgorod nuclear-powered submarine, which can carry the Status-6 (Poseidon) long-range nuclear torpedo with a range of more than 10,000 km was delivered to the Russian Navy in July.120 At the end of July, President Putin also said that deployment would begin within a few months. In November, the United States reported that Russia was preparing for a possible test of the nuclear-powered Poseidon torpedo, which Moscow and Washington both describe as “a new category of retaliatory weapon,” believed to be capable of triggering radioactive ocean swells that could render coastal cities uninhabitable. 121 Russia has also developed the SSC-X-9 (Skyfall) nuclear-propelled cruise missile, which has been observed to be experiencing difficulty. 122 In 2022, there was no publicly available update on Russia’s progress with this missile.

The United Kingdom

As mentioned above, in 2021 the United Kingdom declared in its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy that it would move to an overall nuclear warheads stockpile ceiling from not more than 180 of no more than 260 warheads.123 In addition, the United Kingdom in its national report submitted to the NPT RevCon stated, “This is a ceiling, not a target, and it is not our current stockpile number. This is fully consistent with the longstanding minimum credible deterrence posture of the United Kingdom and we will continue to keep this under review in light of the international security environment.” 124 In October 2017, the United Kingdom started to construct a new Dreadnought-class of four SSBNs to replace the existing Vanguard-class SSBNs. The first new SSBN is expected to enter into service in the early 2030s, but construction has been delayed due to technical problems. (See the Hiroshima Report 2021). The SLBMs to be mounted on the new SSBNs are planned to be equipped with the W93 nuclear warhead, which is under consideration in cooperation with the United States.

The United States

In the 2022 NPR published in October 2022, the United States stated its plans to modernize the Triad of its strategic nuclear forces, and maintain the low-yield nuclear warhead (W76-2) on SLBMs that was promoted and deployed under the previous Trump administration. It also announced that the B83-1 gravity-nuclear bomb would be “retired due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs,” and that the development of the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), which was launched by the previous administration, would be cancelled. Regarding the W76-2, the United States “reassessed the rationale for these capabilities and concluded that the W76-2 currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use. Its deterrence value will be re-evaluated as the F35A and LRSO are fielded, and in light of the security environment and plausible deterrence scenarios we could face in the future.” 125

The NPR also concluded that the SLCM-N was “no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether the SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities.” 126

However, some members of the U.S. Congress as well as high-ranking military officials continue to push for the maintenance of the SLCM-N development budget.127 The National Defense Authorization Act, passed in December, authorized $25 million for the missile’s main body and $20 million for the nuclear warhead it will carry, respectively, for research and development of SLCM-Ns. 128

As for strategic nuclear forces, the 2022 NPR stated, “The three legs of the nuclear triad are complementary, with each component offering unique attributes. Maintaining a modern triad possessing these attributes – effectiveness, responsiveness, survivability, flexibility, and visibility – ensures that the United States can withstand and respond to any strategic attack, tailor its deterrence strategies as needed, and assure Allies in support of our extended deterrence commitments.”129

The timing for renewal of the U.S. strategic delivery vehicles which began deployment during the Cold War is drawing closer. The U.S. modernization plans of its strategic nuclear force as of 2022 are as follows:

➢ Constructing 12 Colombia-class SSBNs, the first of which commence operation in 2031;

➢ Buildin g 400 Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD, the new ICBMs) for replacing 450 Minuteman III; and

➢ Developing and deploying B B-21 next generation strategic bombers as well as the Lo ng Range Stand Stand-Off Weapon

(LRSO ).

The new ICBM was named the Sentinel (LGM-35A).130 And manufacturer Northrop Grumman announced that the first flight of the B-21 is expected to take place 2023. 131 On December 2, the company unveiled the B-21 to the public for the first time.

In the meantime, the United States succeeded in flight tests of hypersonic weapons in May and October, though the June test failed and their efforts lag behind those of Russia and China. The U.S. hypersonic weapons are being developed to carry conventional rather than nuclear warheads (unlike those of China and Russia, which are being developed to carry both).

The United States in its national report submitted to the NPT RevCon reaffirmed the followings: 132

➢ A decision has been taken, in conjunction with NATO, not to deploy land-based nuclear -armed missiles within Europe;

➢ The current U.S. nuclear modernization plan will not increase the number of ICBMs.

➢ The United States has no program to develop nuclear- armed nuclear-powered cruise missiles or torpedoes;

➢ The United States has no program or intent to deploy nuclear warheads on hypersonic glide vehicles or hypersonic cruise missiles.

India

India appears to be pursuing the possession of a strategic nuclear triad. In December 2022, it conducted test-launches of the 5,000 km range Agni-5 land-based long-range missile. 133 India also test-launched a SLBM from the Arihant nuclear submarine in October, and plans to build three S5 submarines capable of loading longer-range missiles, as a follow-on class to the Arihant submarines. 134

In 2022, India also test-launched BrahMos GLCM, 135 Agni 4 MRBM, 136 Prithvi-II, 137 Agni P 138 and Agni 3. 139

In a test conducted by India on March 9, one GLCM landed on Pakistani territory. Pakistan condemned this incident and demanded that India explain what had happened and prevent a recurrence. 140

India’s Defense Ministry stated on March 11, “In the course of a routine maintenance, a technical malfunction led to the accidental firing of a missile. … It is learnt that the missile landed in an area of Pakistan. While the incident is deeply regrettable, it is also a matter of relief that there has been no loss of life due to the accident. … [The government has] taken a serious view and ordered a high-level Court of Enquiry.” 141

Israel

Israel 142 has neither confirmed nor denied possessing nuclear weapons, and its nuclear activities are opaque. In terms of nuclear delivery means, Israel has developed and deployed both nuclear capable ground-launched medium-range ballistic missiles and SLCMs. In January 2020, it reportedly conducted a test launch of its Jericho long-range ballistic missile. 143

Pakistan

Pakistan has prioritized the development and deployment of nuclear-capable short-, medium- and intermediate-range missiles for ensuring deterrence against India. In April 2022, it conducted a flight test of a Shaheen 3 IRBM. 144 Pakistan is also considered to develop MIRVed IRBMs.

North Korea

North Korea continued its active nuclear and missile development in 2022. 145 Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea Kim Jong Un instructed at the Politburo meeting on January 19 to reconsider the moratorium on testing longer-range ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons and to examine the issue on resuming these tests. 146 He also stated at the Celebration of 90th Founding Anniversary of Korean People’s Army on April 25, “the nuclear forces, the symbol of our national strength and the core of our military power, should be strengthened in terms of both quality and scale, so that they can perform nuclear combat capabilities in any situations of warfare, according to purposes and missions of different operations and by various means.” 147

North Korea conducted an unusually frequent series of missile launch tests in 2022, amounting to more than 30 times with approximately 70 missiles. It is highly likely to continue its activities to produce fissile material for nuclear weapons. (See section 9 (B) of this chapter)

In January, a total of 11 missiles were launched across seven occasions, including a hypersonic missile (which flew 700 km on an irregular trajectory, but was analyzed as maneuverable reentry vehicle (MaRV) 148) , a tactical guided missile of the Railway Mobile Missile Regiment (430 km, similar to Iskander), an SRBM (190 km), and a Hwasong-12 IRBM (launched on a lofted trajectory).

In late February and early March, it launched two ballistic missiles for the stated purpose of “developing a reconnaissance satellite system.” At the time of the test on March 5, it explained that “[t]hrough the test, [North Korea] confirmed the reliability of data transmission and reception system of the satellite, its control command system and various ground-based control systems.” 149

Japan and the United States announced the results of their analysis which concluded that the fired missiles used ICBM technologies.

North Korea also launched an ICBM believed to be a Hwasong-17 on March 16, but it exploded in mid-air shortly after launch and so the launch ended in failure. It launched another ICBM on March 24, and announced that it had launched the Hwasong-17 in a lofted orbit from Pyongyang on a mobile launcher. According to KCNA, the missile “traveled up to a maximum altitude of 6,248.5 km and flew a distance of 1,090 km … before accurately hitting the pre-set area in open waters of the East Sea of Korea.” 150 Chairman Kim Jong Un said, “[T]he emergence of the new strategic weapon of the DPRK would make the whole world clearly aware of the power of our strategic armed forces once again.

… [A]ny forces should be made to be well aware of the fact that they will have to pay a very dear price before daring to attempt to infringe upon the security of our country.” 151

On April 17, North Korea conducted a test-flight of its “new-type tactical guided weapon system” which is likely a variant of the KN24 SRBM. It mentioned that the test is to develop the capability of mounting tactical nuclear warheads. 152 It also launched the Hwasong-15 (with a range of about 470-500 km and a maximum altitude of 780-800 km) on May 4; a short-range ballistic missile believed to be an SLBM (with a range of about 600 km and a maximum altitude of about 50 km) on May 12; three ballistic missiles, (including one ICBM flying in a lofted orbit and the other in an irregular one) on May 25; a total of eight SRBMs from four locations, including Pyongyang on June 5; and an SRBM believed to be a KN-23 variant on September 25.

On October 4, North Korea conducted a test launch of an Hwasong-12 IRBM, which flew over Japan for the first time in five years, reaching a maximum altitude of approximately 1,000 km and with a range of approximately 4,600 km. On October 12, it launched two long-range cruise missiles that, according to North Korea, “[were] aimed at further enhancing the combat efficiency and might of the long-range strategic cruise missiles deployed at the units of the Korean People’s Army for the operation of tactical nukes and reconfirming the reliability and technical safety of the overall operational application system.” It also stated that “[t]wo long-range strategic cruise missiles flew for 10,234 [seconds] along an oval and pattern-8 flight orbits in the sky above the West Sea of Korea and clearly hit the target 2,000 km away.” 153

On October 31, North Korea denounced the U.S.-South Korea joint military exercise, and warned, “If the U.S. continuously persists in the grave military provocations, the DPRK will take into account more powerful follow-up measures.” 154 On November 2, North Korea launched 23 missiles— the largest number ever in a single day—including an SRBM, toward the east and west sides of the Korean Peninsula. One of these SRBMs crossed the Northern Limit Line (NLL) and fell into the sea near South Korean territorial waters. 155 The next day, North Korea launched a Hwasong-17 ICBM and two SRBMs toward the Sea of Japan. The ICBM probably failed to fly normally after the first and second stages were detached. However, North Korea claims that the launch of the ballistic missile was a “test-fire of ballistic missile to verify the movement reliability of a special functional warhead paralyzing the operation command system of the enemy.” 156 It has also speculated that the exercise might have been conducted in anticipation of an EMP attack. 157

North Korea conducted another test launch of the Hwasong-17 on November 18. KCNA reported that it was successful, with a maximum altitude of 6,040.9 km, a flight distance of 999.2 km, and a flight time of about one hour and nine minutes. According to the report, Chairman Kim said that the test was to check the reliability of the weapon system and its operation, and that it was “the strict implementation of the top-priority defense-building strategy …on steadily bolstering up the most powerful and absolute nuclear deterrence.” The report also stated, “Kim Jong Un solemnly declared that if the enemies continue to pose threats to the DPRK, frequently introducing nuclear strike means, our Party and government will resolutely react to nukes with nuclear weapons and to total confrontation with all-out confrontation.” 158

80 U.S. Department of State, “Report to Congress on Implementation of the New START Treaty,” April 2022. In May 2021, for instance, the Russian Foreign Ministry reported that the United States had removed 56 ballistic missile launchers, 41 heavy bombers and 4 ICBM silos from its declared arsenal but that Russia was unable to confirm that they were no longer nuclear-capable; in its view, “[t]hus, the figure allowed under … the Treaty is exceeded by the United States by 101.” “Russia Raises Concerns over U.S. Implementation of Arms Control Treaty,” Reuters, May 24, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-accuses-us-exceeding-limits-imposed-by-new-start-arms-control-treaty-2021-05-24/.

81 The United States also had declassified the number of each type of its strategic delivery vehicles through September 2020. However, it has not done so since then.

82 “Western Sanctions Undermine New START Nuclear Arms Control Treaty,” Blitz, August 14, 2022, https://www.weeklyblitz.net/opinion/western-sanctions-undermine-new-start-nuclear-arms-control-treaty/.

83 “Press Briefing,” U.S. Department of State, August 16, 2022, https://www.state.gov/briefings/depart ment-press-briefing-august-16-2022/.

84 Shannon Bugos, “U.S. Conditions Talks on New START Inspections,” Arms Control Today, October 2022, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2022-10/news/us-conditions-talks-new-start-inspections.

85 “Russia Open to In-person Talks with U.S. on Nuclear Arms Treaty,” Reuters, September 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-open-in-person-talks-with-us-nuclear-arms-treaty-2022-09-29/.

86 “Press Briefing,” U.S. Department of State, November 8, 2022, https://www.state.gov/briefings/ department-press-briefing-november-8-2022/.

87 “Russia Had No Choice But to Nix New START Treaty Talks, Says Senior Diplomat,” Tass, November 29, 2022, https://tass.com/politics/1543339.

88 “Russia Says Nuclear Talks with US Delayed Amid Differences,” ABC, November 30, 2022, https:// abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/russia-nuclear-talks-us-delayed-amid-differences-94144918.

89 “Envoy Says Russia to Propose New Timeframe for START Treaty Meeting with US,” Tass, November 30, 2022, https://tass.com/politics/1543391.

90 Ibid

91 Blinken, “On the Extension of the New START Treaty with the Russian Federation.”

92 “President Biden Statement Ahead of the 10th Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” August 1, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/ statements-releases/2022/08/01/president-biden-statement-ahead-of-the-10th-review-conference-of-the-treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons/.

93 “Briefing with Deputy Secretary Wendy R. Sherman on the U.S.-Russia Strategic Stability Dialogue,” January 10, 2022, https://ru.usembassy.gov/briefing-with-deputy-secretary-sherman-on-the-us-russia-strategic-stability-dialogue-011022/.

94 Hibai Arbide and Azamiguel Gonzalez, “US Offered Disarmament Measures to Russia in Exchange for Deescalation of Military Threat in Ukraine,” El Pais, February 2, 2022, https://english.elpais.com/ usa/2022-02-02/us-offers-disarmament-measures-to-russia-in-exchange-for-a-deescalation-of-military-threat-in-ukraine.html.

95 “Россия будет вынуждена реагировать в том числе путем реализации мер военно-технического характера,” Kommersant, February 17, 2022, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5218858.

96 “Russia Says It is in Constant Contact with U.S., Ready for Arms Control Talks – RIA,” Reuters, March 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-says-it-is-constant-contact-with-us-ready-arms-control-talks-ria-2022-03-12/.

97 “Russia Says Dialog with US on Strategic Stability Formally ‘Frozen’,” Press TV, April 3, 2022, https:// www.presstv.ir/Detail/2022/04/30/681279/Russia-US-Putin-Biden-strategic-stability-Ukraine.

98 “President Biden Statement Ahead of the 10th Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” August 1, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/ statements-releases/2022/08/01/president-biden-statement-ahead-of-the-10th-review-conference-of-the-treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons/

99 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.28, November 29, 2021.

100 ICAN, Squandered: 2021 Global Nuclear Weapons Spending, 2022.

101 Sarah Morland, “Nuclear Missiles, Bombs Market to Surge 73% by 2030, Report Says,” Reuters, April 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/nuclear-missiles-bombs-market-surge-73-by-2030-report-2022-04-04/.

102 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.28, November 29, 2021.

103 “Director-General of the Department of Arms Control of the Foreign Ministry Fu Cong Holds a Briefing for Chinese and Foreign Media on the Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War,” China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 4, 2022, https:// www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbxw/202201/t20220105_10478993.html.

104 “Remarks by President Biden Before the 77th Session of the United Nations General Assembly,” September 21, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/09/21/re marks-by-president-biden-before-the-77th-session-of-the-united-nations-general-assembly/.

105 U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, November 2022, p. 94. In this annual report in 2021, Defense Department assessed that “[t]he accelerating pace of the PRC’s nuclear expansion may enable the PRC to have up to 700 deliverable nuclear warheads by 2027. The PRC likely intends to have at least 1,000 warheads by 2030, exceeding the pace and size the DoD projected in 2020.” The U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, November 2021, p. 90.

106 “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference,” China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 30, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_ 665403/202211/t20221130_10983296.html.

107 The U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, p. 167. The U.S. Department of Defense in its previous annual report that China has 100 ICBM launchers and 150 ICBMs. The U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021, p. 163.

108 The U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, p. 94.

109 Ibid., p. 94.

110 Ibid., p. 167.

111 “A Fractional Orbital Bombardment System with a Hypersonic Glide Vehicle?” Arms Control Wonk, October 18, 2021, https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1213655/a-fractional-orbital-bombard ment-system-with-a-hypersonic-glide-vehicle/.

112 François Hollande, “Nuclear Deterrence—Visit to the Strategic Air Forces,” February 19, 2015, http:// basedoc.diplomatie.gouv.fr/vues/Kiosque/FranceDiplomatie/kiosque.php?fichier=baen2015-02-23. html#Chapitre1.

113 “France Launches Program to Build New Generation of Nuclear Submarines,” Marine Link, February 19, 2021, https://www.marinelink.com/news/france-launches-program-build-new-485431; Timothy Wright and Hugo Decis, “Counting the Cost of Deterrence: France’s Nuclear Recapitalization,” Military Balance Blog, May 14, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/05/france-nuclear-recapita lisation.

114 “Russia Tests Nuclear-capable Missile in Warning to Enemies,” Guardian, April 20, 2022, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/20/russia-tests-nuclear-missile-putin-intercontinental-ballistic-weapon?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other.

115 Ibid.

116 “Russia Successfully Conducts Flight Tests of Sarmat ICBM — Commander,” Tass, November 19, 2022, https://tass.com/defense/1539013.

117 Parth Satam, “Russian Nuclear Submarine Successfully Test-Fires Bulava Ballistic Missile Amid Tensions With NATO,” The Eurasian Times, November 3, 2022, https://eurasiantimes.com/new-russian-nuclear-submarine-successfully-test-fires-bulava-ballistic/.

118 “Russia’s Tsirkon Sea-Launched Hypersonic Missile Enters Final Stage of Trials — Top Brass,” Tass, January 20, 2022, https://tass.com/defense/1390793.

119 “Russia’s 1st Regiment of Avangard Hypersonic Missiles to Go on Combat Alert by Yearend,” Tass, August 10, 2021, https://tass.com/defense/1324415.

120 Sam LaGrone, “‘Doomsday’ Submarine Armed with Nuclear Torpedoes Delivers to Russian Navy,” USNI News, July 8, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/07/08/doomsday-submarine-armed-with-nuclear-torpedoes-delivers-to-russian-navy.

121 Jim Sciutto, “US Observed Russian Navy Preparing for Possible Test of Nuclear-Powered Torpedo,” CNN, November 10, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/10/politics/us-russia-possible-torpedo-test/index.html.

122 Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 1, 2020, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2020-03/nuclear-notebook-russian-nuclear-forces-2020/; “Russia’s Nuclear Cruise Missile is Struggling to Take Off, Imagery Suggests,” NPR, September 25, 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/09/25/649646815/russias-nuclear-cruise-missile-is-struggling-to-take off-imagery-suggests.

123 United Kingdom, Global Britain in a Competitive Age, p. 76.

124 NPT/CONF.2020/33, November 5, 2021.

125 U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, October 2022, p. 20.

126 Ibid, p. 20.

127 Lawrence Ukenye and Connor O’brien, “Congress Poised to Shoot Down Biden’s Nuclear Rollback,” Politico, July 6, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/06/congress-biden-nuclear-rollback-00044344; Valerie Insinna, “House Authorizers Approve $45M to Keep Sea-Launched Nuke on Life Support,” Breaking Defense, June 22, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/06/house-authorizers-approve-45m-to-keep-sea-launched-nuke-on-life-support/.

128 “Final Summary: Fiscal Year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act (Senate Amendment to H.R. 7776),” Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, December 2022, https://armscontrolcenter. org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Final-NDAA-Fact-Sheet-v6.pdf.

129 U.S. Department of Defense, 2022 Nuclear Posture Review, October 2022, p. 20.

130 Stephen Losey, “Here’s the New Name of the US Air Force’s Next-Gen Nuke,” Defense News, April 6, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2022/04/05/heres-the-new-name-of-the-us-air-forces-next-gen-nuke/.

131 Stephen Losey, “B-21 First Flight to Come in 2023,” Defense News, May 26, 2022, https://www. defensenews.com/air/2022/05/25/b-21-first-flight-to-come-in-2023/.

132 NPT/CONF.2020/47, December 27, 2021.

133 “India Tests Long-Range Missile for Nuclear Deterrence,” U.S. News, December 15, 2022, https://www. usnews.com/news/world/articles/2022-12-15/india-tests-long-range-missile-for-nuclear-deterrence.

134 “India’s SSBN Program — Challenges, Imperatives,” IndraStra, April 28, 2021, https://www.indrastra. com/2021/04/India-s-SSBN-Program-Challenges-Imperatives.html.

135 “India Successfully Test-Fires Extended-Range Version of BrahMos Missile from Sukhoi” Deccan Herald, May 13, 2022, https://www.deccanherald.com/national/india-successfully-test-fires-extended-range-version-of-brahmos-missile-from-sukhoi-1108807.html.

136 “India Tests Nuclear-Capable Agni-4 Missile,” The Indian Express, June 7, 2022, https://indian express.com/article/india/india-tests-nuclear-capable-agni-4-missile-7956074/.

137 Hemant Kumar Rout, “Night Trial of Surface-to-Surface Nuclear Capable Short-Range Ballistic Missile Prithvi II Successful,” The New Indian Express, June 15, 2022, https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/ 2022/jun/15/night-trial-of-surface-to-surface-nuclear-capable-short-range-ballistic-missile-prithvi-ii-successfu-2466031.html.

138 “India Successfully Test Fires New-Generation ‘Agni Prime’ Ballistic Missile,” NDTV, October 21, 2022, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-successfully-test-fires-new-generation-agni-prime-ballis tic-missile-3452100.

139 Shailaja Tripathi, “Agni-3: India Successfully Test-Fires Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile,” Jagran Josh, November 24, 2022, https://www.jagranjosh.com/current-affairs/agni-3-india-successfully-testfires-inter mediate-range-ballistic-missile-1669262436-1.

140 “Pakistan Seeks Answer from India after ‘Supersonic Missile’ Crashes near Mian Chunnu,” The Express Tribune, March 11, 2022, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2347344/pakistan-seeks-answer-from-india-after-supersonic-missile-crashes-near-mian-chunnu.

141 “India Says it Accidentally Fired Missile into Pakistan,” Nikkei Asia, March 11, 2022, https://asia. nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/India-says-it-accidentally-fired-missile-into-Pakistan.

142 See, for instance, Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Nuclear Notebook: Israeli Nuclear Weapons, 2022,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 17, 2022, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2022-01/nuclear-notebook-israeli-nuclear-weapons-2022/.

143 Don Jacobson, “Israel Conducts Second Missile Test in 2 Months,” UPI, January 31, 2020, https:// www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2020/01/31/Israel-conducts-second-missile-test-in-2-months/ 3481580486615/.

144 “Pakistan Tests Nuclear Missile that can Hit India’s Furthest Point,” Pro Pakistani, April 9, 2022, https://propakistani.pk/2022/04/09/pakistan-tests-nuclear-missile-that-can-hit-indias-furthest-point/.

145 See also “North Korean Missile Launches & Nuclear Tests: 1984-Present,” CSIS Missile Threat Project, https://missilethreat.csis.org/north-korea-missile-launches-1984-present/.

146 Colin Zwirko, “North Korea Hints at ‘Resuming’ Long-Range Weapons Tests after New US Sanctions,” NK News, January 20, 2022, https://www.nknews.org/2022/01/north-korea-hints-at-resuming-long-range-weapons-tests-after-new-us-sanctions/.

147 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Makes Speech at Military Parade Held in Celebration of 90th Founding Anniversary of KPRA,” KCNA, April 26, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202204/ news26/20220426-02ee.html.

148 Vann H. Van Diepen, “Implications of the Second Launch of North Korea’s Second ‘Hypersonic’ Missile,” 38 North, January 18, 2022, https://www.38north.org/2022/01/implications-of-the-second-launch-of-north-koreas-second-hypersonic-missile/.

149 “NADA and Academy of Defence Science Conduct Another Important Test for Developing Reconnaissance Satellite,” KCNA, March 6, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202203/news06/ 20220306-02ee.html.

150 “Striking Demonstration of Great Military Muscle of Juche Korea: Successful Test-Launch of New-Type ICBM,” KCNA, March 25, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202203/news25/20220325-02 ee.html. It was also reported that the U.S. and South Korean officials have concluded that the ICBM launched was a Hwasong-15, not a new Hwasong-17. Hyonhee Shin and Josh Smith, “S.Korea Says N.Korea Staged ‘largest ICBM’ Fakery to Recover from Failed Test,” Reuters, March 30, 2022, https://www. reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/skorea-says-nkorea-staged-largest-icbm-fakery-recover-failed-test-2022-03-30/.

151 “Striking Demonstration of Great Military Muscle of Juche Korea.”

152 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Observes Test-fire of New-type Tactical Guided Weapon,” KCNA, April 17, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202204/news17/20220417-01ee.html.

153 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Guides Test-Fire of Long-Range Strategic Cruise Missiles,” KCNA, October 13, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202210/news13/20221013-03ee.html.

154 “Statement of Spokesman for DPRK Foreign Ministry,” KCNA,” October 31, 2022, http://www.kcna. co.jp/item/2022/202210/news31/20221031-09ee.html.

155 Jamie McIntyre, “Tensions Rise on Korean Peninsula as US, South Resume Large-Scale Exercises, North Fires More Missiles,” Washington Examiner, November 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer. com/policy/defense-national-security/tensions-rise-on-korean-peninsula-as-us-south-resume-large-scale-exercises-north-fires-more-missiles.

156 “Report of General Staff of KPA on Its Military Operations Corresponding to U.S.-South Korea Combined Air Drill,” KCNA, November 7, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202211/news07/ 20221107-01ee.html.

157 “North Korea, Testing EMP Attack in ICBM Test Firing,” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, November 7, 2022, https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOGM07BPU0X01C22A1000000/. (in Japanese)

158 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Guides Test-fire of New-type ICBM of DPRK’s Strategic Forces,” KCNA, November 19, 2022, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2022/202211/news19/20221119-01ee.html.

-1-150x150.jpg)