Hiroshima Report 2023(3 ) Humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons

A) Main arguments

Discussions on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons began at the Oslo Conference in 2013, and continued through the Nayarit and Vienna Conferences in 2002. Since the 2015 NPT RevCon, the Humanitarian Group, which focuses on the humanitarian dimensions of nuclear weapons, has emphasized the significance of starting negotiations on a legally binding instrument on prohibiting nuclear weapons. The result was the adoption of the TPNW in 2017.

On June 20, 2022, in conjunction with the First Meeting of the States Parties of the TPNW, the Fourth Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons was held in Vienna. More than 800 delegates representing 80 states, the UN , the International Committee of the Red Cross, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and other relevant international organizations, civil society organizations and academia participated in the Conference , and many experts, in addition to participating countries and in ternational organizations, also made statements. According to the Chair’s summary, “ The [Conference ] addressed the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, including effects on human health, the environment, agriculture and food security, migration and the economy, as well as the risks and likelihood of authorized, unauthorized or accidental detonations of nuclear weapons, international response capabilities and the applicable normative framework and identified areas where further research and investigation appears necessary.”48 In addition, the Chair’s summary listed the following as the main points of the reports and discussions during the Conference, inter alia:

➢ It is impossible to appropriately address the immediate humanitarian emergency and long-term consequences of nuclear weapon detonations. What we cannot prepare for, what we cannot respond to, we must therefore prevent.

➢ Nuclear winter would likely affect the entire globe.

➢ Nuclear weapons detonations have vaster, truly global and longer persistin g consequences than we thought before.

➢ Atmospheric nuclear tests, although conducted decades ago, are responsible for serious health effects and long lasting environmental degradation.

➢ We still lack an integrated full picture of the impact of nuclear weapons. More interdisciplinary work and further research on the interplay between short-, mid – and long-term effects are required for deepening our knowledge. Not only more research, but also more discussion and consideration is necessary in order to bring more clarity and findings on which a fact-based policy can be developed.

➢ The propagation of smaller tactical, better usable nuclear weapons is disconcerting. Even the detonation of a single so -called small nuclear weapon would have devastating and compounding effects and, in addition, carry a very high risk of triggering an escalation to a limited or all-out nuclear war.

Furthermore, the Chair person of the Conference emphasized in his summary the danger of nuclear deterrence, stating: “The threat of nuclear weapons use declared by leading Russian politicians showcases how real this risk is today and underscores the fragility of a security paradigm based on the theory of nuclear deterrence. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine underscores the fact that nuclear weapons do not prevent major wars, but rather embolden nuclear-armed states to start wars.”

At the NPT RevCon, 145 NNWS (including Austria, Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Switzerland) issued a “Joint Humanitarian Statement ,” in which they stated: “Our countries are deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons”; The Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons in 2022 revealed that “no State, group of States, or indeed the international humanitarian system as a whole, could respond to the immediate humanitarian emergency a nuclear weapon detonation would cause. Nor could they provide adequate assistance to victims”; “the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons … have deep implications for human survival, for our environment, for socioeconomic development, for our economies, and for the health of future generations”; and “The only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons will never be used again is through their total elimination.” 49

South Africa and Switzerland) issued a “Joint Humanitarian Statement ,” in which they stated: “Our countries are deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons”; The Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons in 2022 revealed that “no State, group of States, or indeed the international humanitarian system as a whole, could respond to the immediate humanitarian emergency a nuclear weapon detonation would cause. Nor could they provide adequate assistance to victims”; “the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons … have deep implications for human survival, for our environment, for socioeconomic development, for our economies, and for the health of future generations”; and “The only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons will never be used again is through their total elimination.” 49

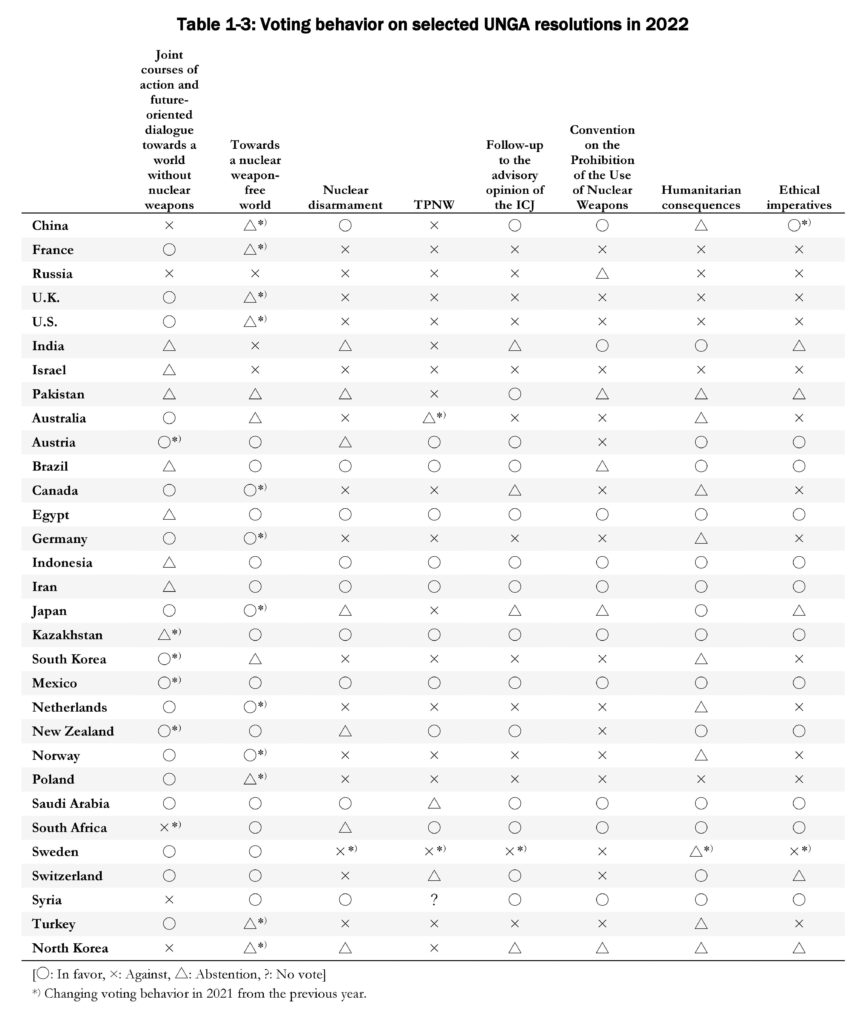

At the 2022 UNGA, countries mainly belonging to the Humanitarian Group, as in the previous year, proposed a resolution titled “Humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons.” 50 The resolution stated, inter alia, that it “ highlights the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons and calls on all states to prevent any use or proliferation of nuclear weapons and to achieve nuclear disarmament. ” The voting behavior of countries surveyed in this project on this resolution is as follows:

➢ 138 in favor ( Austria, Brazil, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Switzerland, Syria and others); 14 against (France, Israel, Poland, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States and others); 31 absten tions (Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Germany, South Korea, North Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Sweden, Turkey and others)

Furthermore, voting behavior on the resolution titled “Ethical imperatives for anuclear-weapon-free world world,”51 which “calls upon all states to acknowledge the humanitarian impacts and risks of a nuclear weapon detonation and makes a series of declarations about the inherent immorality of nuclear weapons underlying the need for their elimination ,” led by the Humanitarian Group countries, was:

➢ 131 in favor (Austria, Brazil, China , Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mexico, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Syria and others); 38 against (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Israel, South Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and others), 11 abstentions (India, Japan, North Korea, Pakistan, Switzerland and others)

NWS have not been receptive to humani -tarian issues in nuclear disarmament from the outset . While the United Kingdom and the United States attended the Third International Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons in 2014 , NWS kept their distance from these issues , especially when the Humanitarian Group began to officially pursue a legal prohibition of nuclear weapons.

However, the Japan-U.S. “ Joint Statement on the Treaty on the NPT ” in January 2022 stated, “ In a tense international security environment and recognizing the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons, it is more urgent than ever to support non-proliferation and arms control processes that are persistent, practical, proactive, and progressive. ”52

With regard to the UNGA resolution on nuclear disarmament led by Japan in 2022 , the amount of writing on humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons issues has increased significantly : the 2021 resolution just referred, “Recognizing the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from the use of nuclear weapons”; and the 2022 resolution stated, “Reiterating deep concern at the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons, reaffirming that this awarenes s ought to continue to underpin our approaches and efforts towards nuclear disarmament, and welcoming the visits of leaders, youth and others to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in this regard.”

B) Victim assistance and environmental remediation

Assistance to victims of nuclear weapons-related activities , including their use, test and production , and remediation of the contaminated environment are also important from the perspective of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. Article 6 of the TPNW stipulates provision of assistance to victims affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons , and implementation of necessary and appropriate measures towards the environmental remediation of areas so contaminated.53 There are also some cases that countries which have not signed or ratified the TPNW addressed on an individual basis.

At the First Meeting of the States Parties to the TPNW(1MSP), based on a working paper54 submitted by Kazakhstan and Kiribati as co-facilitators for these issues, following actions which should be taken by the states parties were listed in the Vienna Action Plan, inter alia:

➢ Engag ing with relevant stakeholders, including international organizations, civil society, affected communities, indigenous peoples, and youth, and work cooperatively to advance effective and sustainable implementation of Articles 6 and 7.

➢ Engaging and promoting information exchange with states not party to the Treaty that have used or tested nuclear weapons, or any other nuclear explosive devices, on their provision of assistance to affected states parties for the purpose of victim assistance and environmental remediation.

➢ Establishing national focal points for Articles 6 and 7, with appropriate contact details for consultations, no later than 3 months after the 1MSP.

➢ Adopting or adapting and implementing relevant national laws and policies on Articles 6 and 7, where appropriate.

➢ Coordinating and developing mechanisms , where to facilitate the provision of the international cooperation and technical, material , and financial assistance.

➢ Cooperating with the UN system, relevant international, regional, or national organizations or institutions, relevant non-governmental organizations or institutions, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and others others.

➢ Discussing the feasibility of, and proposing possible guidelines for, establishing an international trust fund for states that have been affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons.

➢ Developing national plans for implementation of their victim assistance and environmental remediation obligations, which include budgets and timeframes.

Participating countries of the 1MSP also decided to establish informal working groups on victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation and assistance, which will be co-chaired by Kazakhstan and Kiribati between the first and second MSPs.

At the NPT RevCon, the NAM countries stated in their working paper, “ The [NAM] underlines the need for increased attention to the problems of safety and contamination related to the discontinuation of nuclear operations formerly associated with nuclear weapons programmes, including, where appropriate, the safe resettlement of any displaced human populations and the restoration of economic productivity to affected areas. In this regard, the Group acknowledges the existence of a special responsibility towards the affected people and areas, including those in the former United Nations Trust Territories that have been adversely affected as a result of nuclear weapon tests conducted in the past.”55 Five Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan, proposed in the working paper that the following issue should be included in the final document document: “The tenth Review Conference reiterates the appeal of the 1995, 2000, 2010 and 2015 Conferences to all Governments and international organizations that have expertise in the field of clean-up and disposal of radioactive contaminants to consider giving appropriate assistance , as may be requested, for radiological assessment and remedial purposes in affected areas, while noting the efforts that have been made to date in this regard.”56 In the draft final document, the following sentence was included: “The Conference welcomes the increased attention in the last review cycle on assistance to the people and communities affected by nuclear weapons use and testing and environmental remediation following nuclear use and testing and calls on States parties to engage with such efforts to address nuclear harm.”

In addition to the issues mentioned above, the following developments were reported in 2022 regarding victim assistance and environmental remediation:

➢ In June, President Biden signed into law an amendment to the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which extends the validity period of the law by two years for residents who have suffered from cancer or other cancers as a result of exposure to radiation from atmospheric nuclear tests conducted during the Cold War. The Act provides $5 0,000 to $100,000 in compensation to workers involved in the mining, refining, and transportation of uranium for use in the manufacture of nuclear weapons, as well as to those involved in nuclear testing, and to residents who lived in certain areas around the Nevada Test Site. According to the Department of Justice, more than 39,000 people have been approved for compensation

under the law so far. 57

➢ The Marshall Islands, Fiji, Nauru, Samoa, and Vanuatu submitted a resolution to the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR) requesting assistance in addressing the consequences of nuclear tests.

Nuclear -armed states , however, opposed the resolution. The United States, the United Kingdom, and India argued that the UNHCR was not the appropriate forum to raise this issue. 58

➢ In early 2022, the United States and Marshall Islands began negotiations on renewing the 20-year -old compact, which expires in October 2023. Under the existing agreement, the United States is responsible for providing radiation -related health care services and continued monitoring and environmental assessments on the affected atolls. 59

➢ Japan provides assistance to victims under the “Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act,” but there continues to be debates and court cases regarding the certification of atomic bomb survivors and the scope of assistance.

48 “Chair’s Summary,” Fourth Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, Vienna, June 20, 2022.

49 “Joint Humanitarian Statement,” 10th NPT RevCon, August 22, 2022.

50 A/RES/77/53, December 7, 2022.

51 A/RES/77/67, December 7, 2022.

52 “Japan-U.S. Joint Statement on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT),” January 21, 2021, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press3e_000308.html.

53 Regarding assistance to victims of the use or testing of nuclear weapons and restoration of the environment, see, for instance, Bonnie Docherty, “Implementing Victim Assistance, Environmental Remediation under Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty,” Human Rights@Harvard Law, July 14, 2021, https://hrp. law.harvard.edu/arms-and-armed-conflict/implementing-victim-assistance-environmental-remediation-under-nuclear-weapon-ban-treaty/.

54 TPNW/MSP/2022/WP.5, June 8, 2022.

55 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.21, November 22, 2021.

56 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.39, December 15, 2021.

57 “Extension of Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, Averts Expiration,” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, June 8, 2022, https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOCB089GA0Y2A600C2000000/. (in Japanese)

-1-150x150.jpg)