Hiroshima

HATANO Hiroshi

It takes four hours to travel from Tokyo to Hiroshima by the Shinkansen bullet train and 90 minutes by plane, but only those who are unfamiliar with Hiroshima will board a plane thinking that it will be faster. In fact, Hiroshima Airport is located in a highly inaccessible area, and it takes around an hour to get from the airport to Hiroshima City.

If you take into account the time it takes to get to Haneda Airport and to board the plane, the entire trip will take around four hours. Whether you take the Shinkansen or an airplane, the only difference is the duration you will be seated. I was still undecided if I wanted to take the Shinkansen or an airplane to Hiroshima, but the answer I eventually arrived at was that the best way to travel to Hiroshima is to reserve a Green Car seat on the Shinkansen.

The price of a Shinkansen Green Car ticket is almost the same as that of an economy class flight ticket, but it feels a lot more comfortable for the duration you are seated. There is almost never a passenger seated next to you. It would be perfect if you could grab a delicious egg sandwich at Daimaru in Tokyo Station and bring it along with you.

However, I started to regret not taking the airplane after passing Shin-Kobe, and this feeling only intensified as the train passed Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture, which felt like an incredibly large area. Sitting down for four continuous hours was not easy. For a resident of Tokyo like me, Hiroshima feels like a vast, distant place. Even Okinawa, Hokkaido, and Kyushu feel much closer when we travel by plane.

I started fiddling with the lens of the camera I had bought for this trip to pass time. It was an Elmar 3.5cm lens made in Germany in 1938. It is amazing that a lens made in the pre-war years can be used with a modern Leica digital camera, but to be honest, it is really difficult to use.

The assignment I had received this time was to stay in Hiroshima for a while and take photos on the theme of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. I had thought about declining this assignment as it was a challenging subject. To begin with, I knew very little about the damage caused by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

My only encounters with this topic had been reading Barefoot Gen in elementary school, visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum during a school excursion in junior high school, and listening to an A-bomb survivor talk about his experience in front of the Atomic Bomb Dome. I only remember fragments of what I had learned, besides a vague awareness that nuclear weapons were bad.

I have been to Hiroshima countless times as an adult, but I had previously only been to places like Kamiyacho and Hacchobori to drink lemon chuhai while enjoying grilled oysters, eat okonomiyaki, and buy souvenirs such as Carp merchandise and fresh momiji manju.

I had neither any connection to Hiroshima nor any knowledge of the atomic bombing, so I thought this would be a good opportunity to forge a bond with this city and learn more about the bombing of Hiroshima. I got hold of a camera lens from the pre-war years because I wanted to take pictures of the present Hiroshima using a lens that would likely have been used in Hiroshima in the period immediately before and after the atomic bombing.

When I look at old photos, I realize they always have a raw, monochrome appearance. The raw and monochromatic nature of these photos seems to diminish the realism of the subjects of the photos. To exaggerate a little, it almost feels as if these monochrome photos make their subjects come across like historical facts from the distant past.

This has been upended by a project launched by Niwata Anju and Watanabe Hidenori at the University of Tokyo, which uses AI to colorize monochrome photos from the past.

In their book Recovering the Pre-war Years and the War Using AI and Colorized Photos, the authors describe how photos can be made more realistic through their colorization. The resulting photos stir up emotions that cannot be experienced through monochrome photos. It is a wonderful work that drags the landscape of the past into the present and bridges the chasm and the temporal gap between the past and the present.

My objective of using a pre-war lens to create monochrome photos of present-day Hiroshima is to bring us back to the past. Of course, the subjects of my photos are from the present, but I hope to bridge the chasm and the temporal gap between the past and the present by nudging the audience towards the past.

Taking color photos allows me to visually capture the development and peace in Hiroshima, and to be honest, these elements are a lot easier to capture in color than in monochromatic gradations. However, one unintended consequence of shooting in color is the feeling that I am somehow abandoning the past.

I have explained the reasons for choosing to take monochrome photos at length because I believe people may not understand if I do not discuss them. After all, I cannot compare myself to Niwata and Watanabe, who have created works that can move people profoundly even in the absence of words.

The works of these two artists were on display at the Hiroshima City Library, making that my first destination. The library had five color photos on display along with a variety of documents. The two children in the middle are said to be siblings.

The atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima six year after the photos were taken. The older brother carried his younger sister, who was severely injured by the bomb, on his back and took her to a clinic after running away from the flames for over two kilometers. The brother later died, and the sister was nowhere to be found.

The Atomic Bomb Dome is located near the library, so I went there next. It had been 15 years since I last visited the dome to take photos of it while traveling around Japan. An elderly man had seen me taking photos of the dome then and approached me to tell me about the atomic bombing. He also brought me around the park somewhat assertively to show me where I could take better pictures.

I was thinking, “If this were overseas, they would probably ask me for payment at the end…,” and at that very moment, the man asked me to pay him 2,000 yen as a guide fee at the end. I laughed it off thinking it was a Hiroshima joke, but the man got really angry, so I eventually paid him 1,000 yen as a compromise. I never saw that man again.

When I was there this time, I saw many junior high school students on school excursions being shown around by guides and listening to what seemed to be narrators recounting the stories of A-bomb survivors. I remember having a similar experience when I was a junior high school student, but at that time, the narrators were those who had experienced the bombing themselves as adults. There were also many young narrators, and in hindsight, that now feels like an invaluable experience.

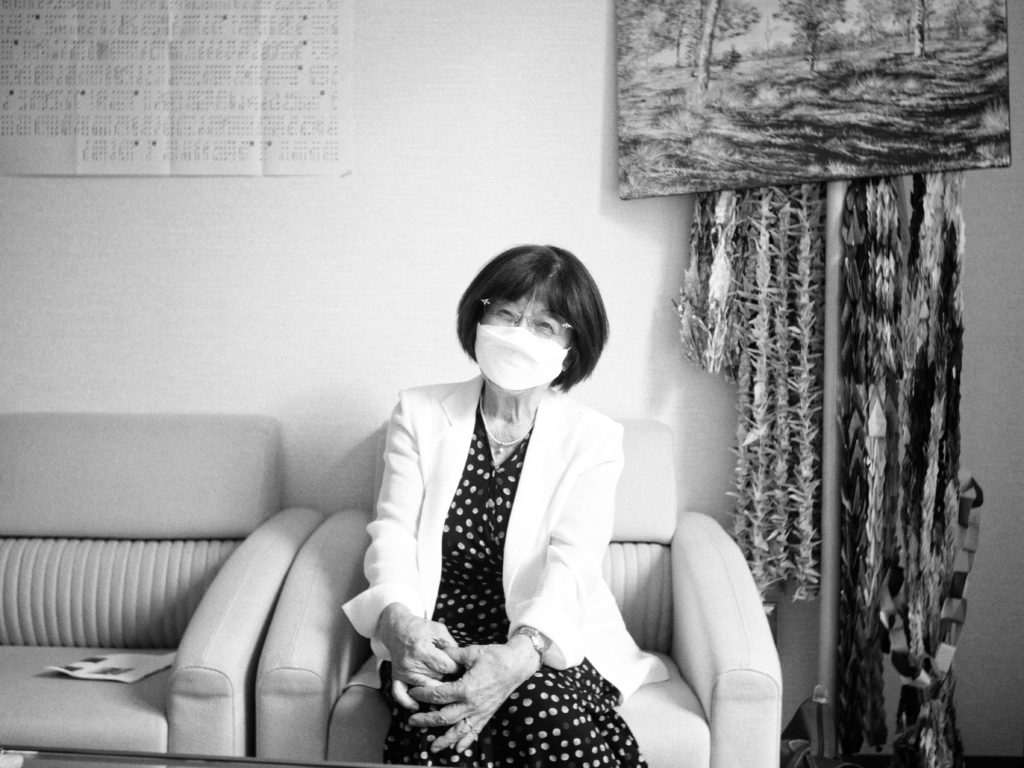

Even someone who was just 8 years old at the time of the bombing would be 84 years old now. I desperately asked around to see if there was any way I could hear from an A-bomb survivor, and 84-year-old Yahata Teruko readily agreed to my request.

Although my PCR test had come back negative, I was sure that she and her family would not like the idea of coming into contact with a young stranger from Tokyo. I almost wanted to hide the fact that I came from Tokyo if possible.

Although I was a little intimidated by Ms. Yahata at first, she treated me just as she would anyone else. I believe everyone who has ever met her would feel the same. Ms. Yahata is a cheerful, chatty lady who seems to worry more about others than herself.

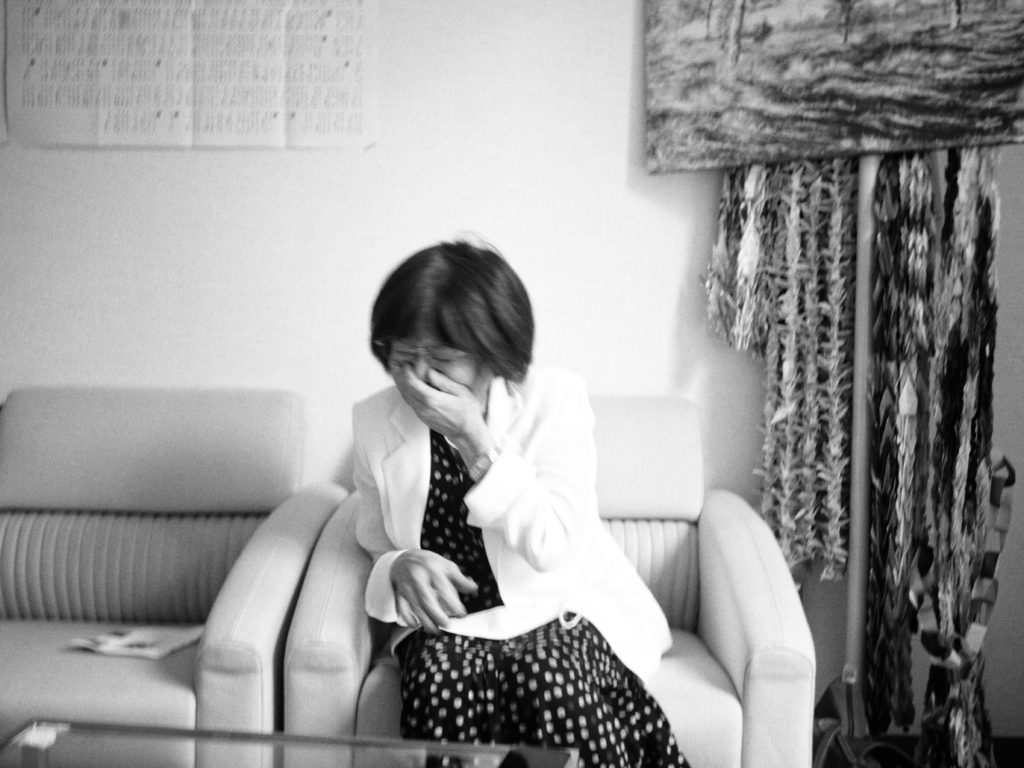

Everything Ms. Yahata said in her cheerful tone was painful to listen to. Perhaps she had maintained a cheerful tone to ease the psychological burden of those listening to her.

Ms. Yahata was 8 years old during the atomic bombing, whose blast made her lose consciousness. When she eventually came to, she could not see anything as the surroundings were dark from the debris. Her mother pulled out a futon in their half-destroyed apartment and told her that they were all going to die together.

At that time, she thought that the second and third bombs would soon be dropped, and that there was no chance of surviving. As her entire family crept under the futon and prepared to die, Ms. Yahata was struck by the warmth of being surrounded by her family and felt an odd sense of relief.

There is actually a scene like this in Barefoot Gen. The protagonist Gen’s father, sister, and brother were all trapped in their apartment, which had collapsed in the blast, and they were unable to move as the flames drew closer. Gen and his mother wanted to die with the rest of the family, but Gen’s father implored them to run and stay alive.

If I were ever in a position of being trapped like this, I would naturally tell my wife and children to run. But if my wife and children were the ones who are trapped, I would want to die together with them. When I was a child, I used to think that running away was clearly the right thing to do and that dying together would be a grave mistake, but as I grew up and started my own family, I no longer feel the same.

Barefoot Gen is based on the actual experience of its author, Nakazawa Keiji, who had lost his father, sister, and brother in the atomic bombing. Gen’s father Daikichi is based on Nakazawa’s father, so Daikichi’s appearance greatly resembles Nakazawa’s own appearance.

Ms. Yahata and her family later evacuated and settled in Yamaguchi Prefecture. Although her entire family was safe and her father found a job at Meiji Seika, life was extremely hard. Prices were soaring on the black market, and they had no clothing or other belongings to trade for food. There was no farmland either, so they had nothing to eat. Their food crisis deteriorated to the point that it was even worse than during the war.

Ms. Yahata’s family often cooked a little rice with a large amount of water and divided it among the family. Every day, they drank a lot of gruel and only ate around two spoonfuls of rice. Ms. Yahata, who was in elementary school at the time, understood the situation and put up with it, but her three-year-old brother kept crying because he could not get any rice no matter how hard he scooped. Even today, she still regrets not having shared her food with her brother at the time, but she was already at her limit then.

I was at a loss for words while listening to Ms. Yahata’s account. If I had heard her story when I was in junior high school, I would probably have empathized with Ms. Yahata, but now, I have a five-year-old child myself. If I were in the position of Ms. Yahata’s parents, I am not sure if I would be able to bear having a small child starve so badly even if I could endure being hungry myself.

Perhaps because of her experience from this period of her life, Ms. Yahata is fond of offering delicious food to others. She has also had negative experiences with telling people from other prefectures that she was a victim of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. This was probably why she did not look uncomfortable at all when meeting someone like me who had come from Tokyo. I parted ways with Ms. Yahata after taking several photos of her.

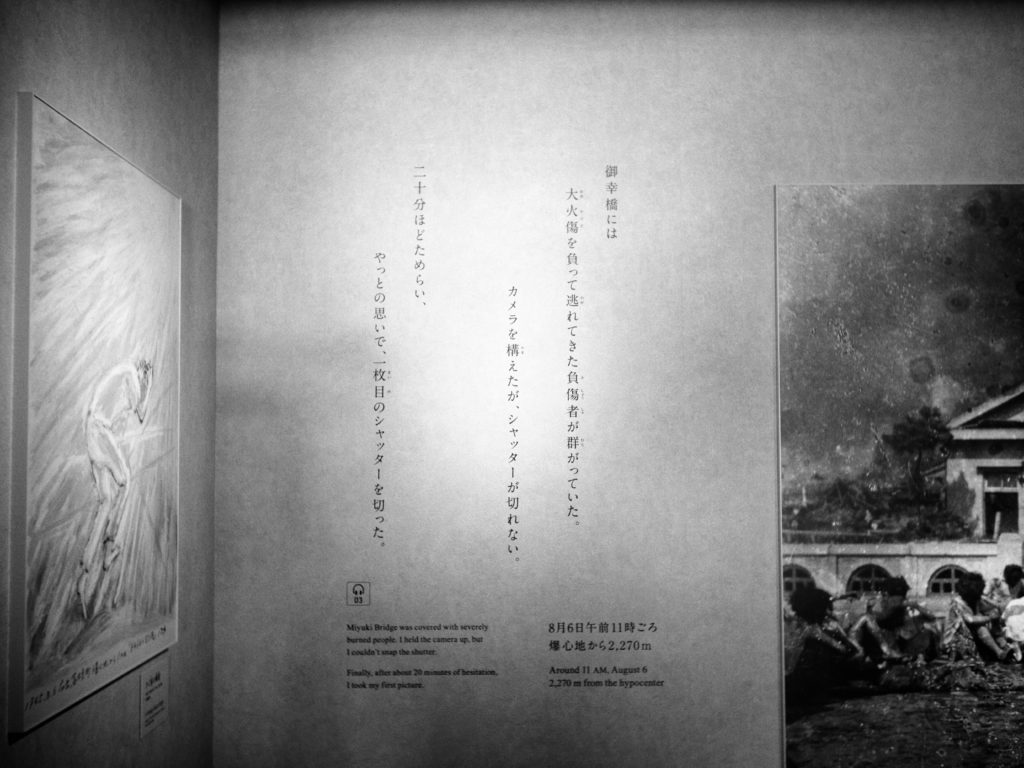

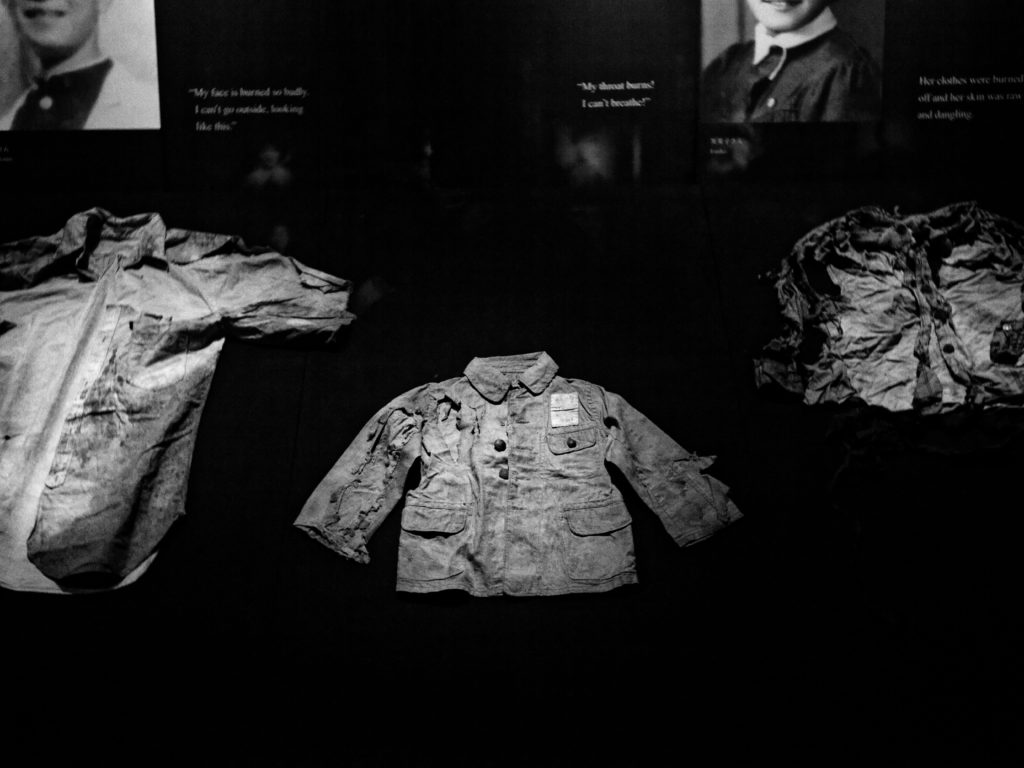

I then visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which had been renovated in 2019 to overhaul its exhibits. Before the renovation, the museum was rather eerie as it had featured items such as mannequins with their skin peeling off, but the museum is now focused on showcasing real historical exhibits instead of props.

Among the exhibits was a large, close-up group photo of many children and their teacher. Everyone in the photo was smiling, and I wonder what they were said when the picture was taken. Looking at the photo through my viewfinder made me feel as if I was the one photographing them. This was a feeling I experienced only when I was looking through the viewfinder, but not when I looked at the photo I had taken on my computer.

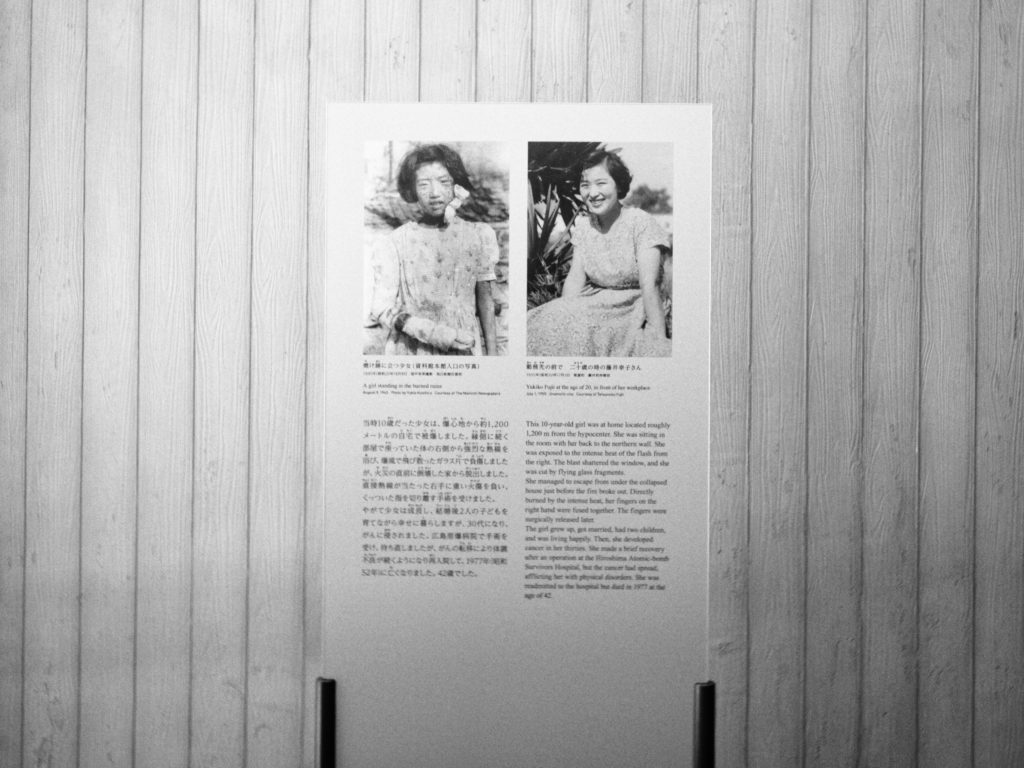

At the entrance of the exhibition was a photo of a girl with a painful expression and injuries to her face and right arm. I might not be able to look her in the eye if this had been a color photo.

There was also a photo of the streets of Hiroshima City right after the bomb was dropped, which means it had been taken by someone in Hiroshima. Sometimes it is possible to take pictures of a devastated area that you have no personal connection to and feel nothing for as you can think of it as someone else’s problem, but how could anyone take pictures of their own city in such a horrific state? I am sure that the parents of the little girl with injuries to her face and right arm would not have been able to take a picture of her.

The newspaper reported on the anguish of the photographer who had taken the picture, “I don’t care if others think that I’m cruel or I’m a devil. I just had to take at least one picture of what happened…” This photographer might have been criticized at the time, but I am very grateful to him for taking this photo, as it amplified my previously vague conviction that nuclear weapons are wrong.

A lunch box and a water bottle were on display in a dimly lit exhibition hall. These items were discovered beside the body of a 13-year-old boy who was killed in the atomic bombing and later found by his mother. The bento and its contents, including the rice and fried potatoes, were all real. Although the museum could have used a replica bento box, they insisted on showcasing the actual specimens.

“We have kept the lighting here dim to preserve the integrity of the specimens,” the museum’s director Takigawa told me. I could not help but wonder in Hiroshima dialect why the museum’s director was taking the trouble to show me around personally. I was really grateful, but I had already been mentally prepared for everything to be completely new to me, if I may say so myself.

“I had shown President Bach [of the International Olympic Committee] around a while ago,” Takigawa said casually with a chuckle. I felt the pressure on me go up another notch.

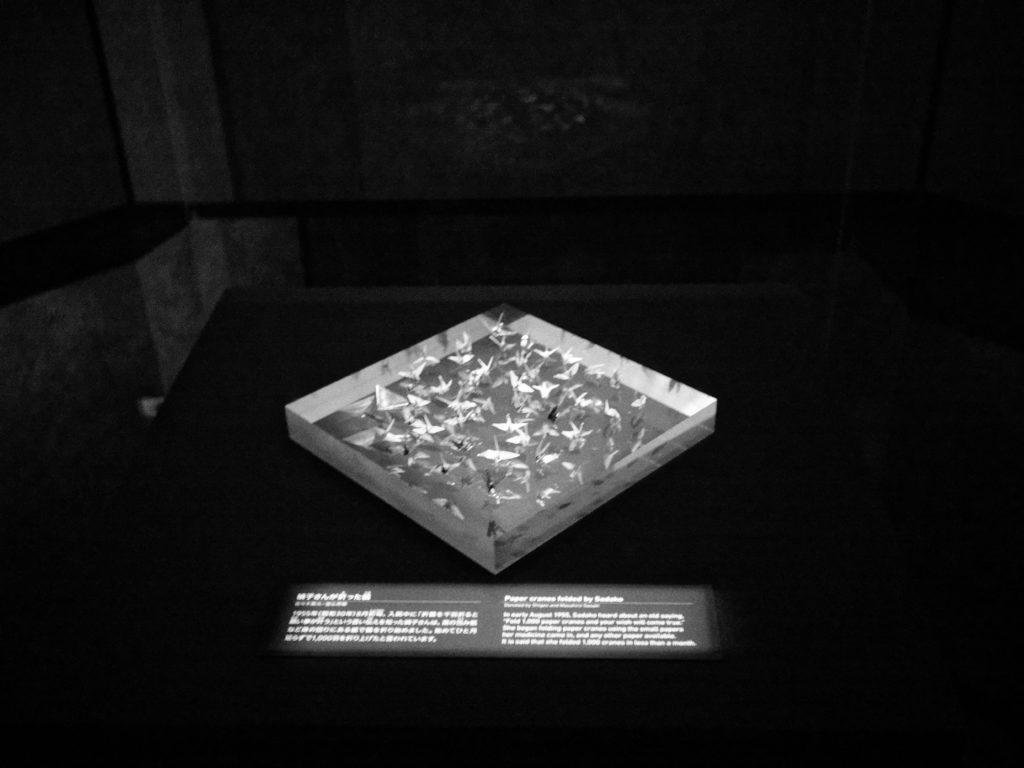

Another exhibit showcased the paper cranes that Sasaki Sadako had folded when she was hospitalized. Sadako was two years old when the atomic bomb dropped, and she was later diagnosed with leukemia in the winter of her sixth year in elementary school. Sadako’s father received her elementary school graduation certificate on her behalf, but she was unable to attend junior high school and died in the fall of her first year of junior high school at the age of 12, just over eight months after receiving her leukemia diagnosis.

Sadako had continued to fold paper cranes in the belief that folding a thousand paper cranes would allow her to recover. This exhibit not only features the cranes she had folded but embodies her hopes and prayers as well.

I am a patient of multiple myeloma, a kind of blood cancer like leukemia. I am still alive today thanks to the dramatic progress in medicine since Sadako’s time, but unfortunately, multiple myeloma is an incurable disease. I am living my life in a carefree way with the knowledge that death will arrive someday.

In this regard, I believe I can understand at least some of Sadako’s emotions and physical suffering, including her frustration, her anger, her feeling of how unfair it all felt, and the mind-numbing pain. The physical pain of diseases like these sometimes makes me wish that I was dead.

In reality, leukemia has a poor prognosis and is not a disease that someone can recover from by simply folding paper cranes. But if I had been hospitalized in the same hospital as Sadako, I would definitely fold paper cranes for her every day. Sadako’s exhibit resonated with me so deeply that it was almost too painful to bear.

The last exhibit was another photo of the girl with injuries to her face and right arm, juxtaposed with a photo of a smiling woman. When the photo of the injured girl was examined two years ago during the renovation of the museum, someone reached out and claimed that the girl in the picture might have been his mother. After careful analysis of the two photos, the girl was confirmed to be his mother.

The injured girl had in fact survived the bombing. She grew up and eventually had her own family. I never expected to feel such an overwhelming sense of relief at the end. What a wonderful exhibit. I then found out that the girl later died of cancer at the age of 42.

I felt depressed all over again, but I did not want to look on her, or on Sadako for that matter, with pity. As a cancer patient, I understand that having others take pity on us is one of the most miserable feelings.

Takigawa, the museum’s director, told me that one of the challenges moving forward is to pass on the stories of the damage caused by the atomic bomb to future generations. There is no way we can stop the A-bomb survivors from becoming older.

The atomic bomb was dropped 76 years ago, and survivors are still around today. The children and grandchildren of these survivors are also around. as one generation gives way to the next, and as we move further away from Hiroshima physically, the memories of the past will inevitably fade.

This is because a new generation will have vivid memories of the experiences of that particular generation. For survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, “that day” would probably refer to August 6th. For survivors of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, “that day” would refer to August 9th. And for those who had listened to the radio broadcast of Emperor Hirohito’s announcement of the end of war, “that day” might be August 15th.

“That day” may also be the day the Great Hanshin Earthquake struck or the day the Great East Japan Earthquake struck for those affected by these disasters, or the day someone had lost their family member or loved one, and for many other people, the day COVID-19 started spreading. It refers to the day from which someone’s life would no longer be the same. For me, it was the day I found out about my illness.

I used to think “that day” in the case of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the catalyst that brought about the end of the war. But for the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a different war had begun on “that day.” I would like to take seriously each person’s “that day,” even that of someone I have not met.

Takigawa, the museum’s director, told me that he just wants people to visit the exhibition. I agree with him completely, and I hope that people will come from all over Japan and other countries to see the exhibition. There are many different opinions about nuclear weapons, and I believe that the complete eradication of nuclear weapons is practically impossible because no country in possession of nuclear weapons would be willing to give them up. As long as the technology to manufacture nuclear weapons exists, there will be countries that want to have nuclear weapons in the future.

Anyone who takes a look at the exhibits at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum will clearly see why nuclear weapons must not be used. If countries that own nuclear weapons claim that they serve as nuclear deterrence, I believe that the same function is served in Hiroshima by the exhibits on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Those who had visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum on a school excursion should definitely visit it again. The experience is completely different from the perspective of an adult. When I read Barefoot Gen as a child, I had read it from the perspective of the protagonist Gen. But when I read it again as an adult, I did so from the perspective of his parents. Having a different perspective of something transforms your perception and experience of it.

It is the same with Ghibli movies and Sazae-san, which I often watched as a child. I used to watch Sazae-san from the perspective of Katsuo when I was a child, but now I watch it from Masuo’s point of view, to the extent that I feel a little depressed when I compare Masuo’s personality traits with my own.

While there may be concerns about passing on Hiroshima’s stories as A-bomb survivors continue to age, we should probably also look forward to the fact that those who have been told these stories are growing up too.

I had the opportunity to attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony held on August 6th. Although there were restrictions imposed on the number of guests and members of the press at the event due to the COVID-19 situation, I was offered a press pass and a seat as a journalist. The hotel I was staying at also appeared to be the place of accommodation of Japanese and foreign dignitaries, so security was tightened the day before the event and security details were deployed. I was checked thoroughly even when I was just moving about the lobby.

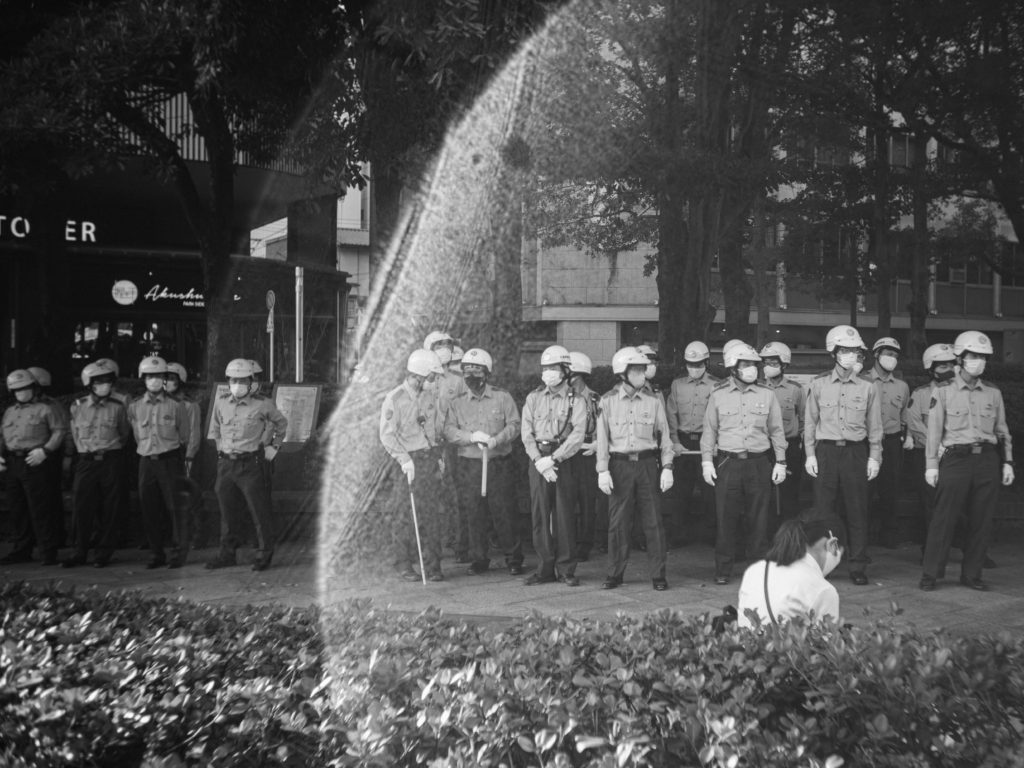

I headed to the Peace Memorial Park a little earlier than the time the ceremony was scheduled to begin. Protestors had lined up in front of the Atomic Bomb Dome and were chanting anti-nuclear slogans through their loudspeakers. I understood what they were trying to do; I oppose nuclear weapons as well. However, Japan does not own nuclear weapons, and there is no movement here with that goal. If there were a movement like that, Japan’s people and opposition parties would be very much opposed to it. In fact, nuclear powers such as the U.S. and China would never allow that to happen.

There were also silent protestors holding placards imploring everyone to pray quietly on August 6th. Police officers had been deployed to separate them from the protestors with loudspeakers, perhaps because of confrontations that had taken place between the two groups. Both the silent protestors and the police officers are probably against nuclear weapons, but I had my doubts about those with loudspeakers.

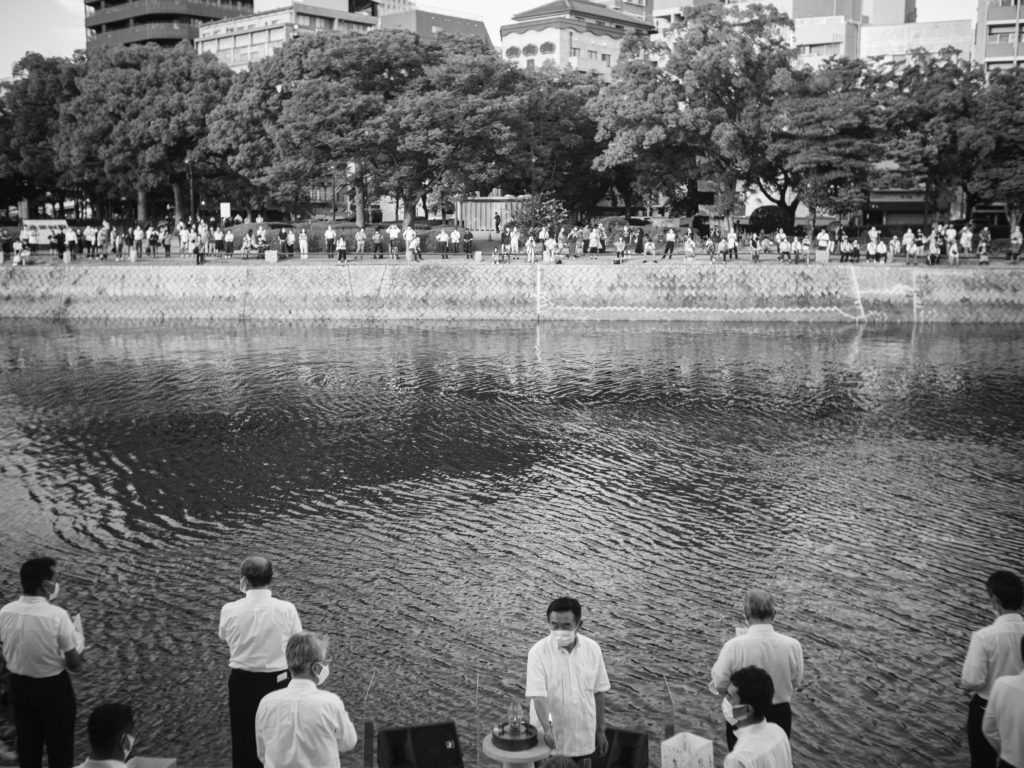

Water was offered at the Cenotaph just before the ceremony began. The A-bomb victims needed water. The bomb was dropped on a hot midsummer day just like today. There must have been many victims who had died after drinking water, but there were probably also many victims who had died without being able to drink.

The ceremony began with the airing of 4,800 names of recently deceased A-bomb victims. In total, the names of 328,929 people have been aired at the Cenotaph so far.

There were news reports that Prime Minister Suga had accidentally skipped some parts of his speech, but I did not notice that when I was there. Unlike TV broadcasts, there were no subtitles for the audience there, and more importantly, protesters were shouting “Suga, go home!!” as Prime Minister Suga was reading his speech in the quiet hall.

I guess the protestors were trying to seize the right moment to draw attention to themselves, but I felt that they did not have to yell at a moment like that. Although I was there as a journalist, I had also wanted to pray quietly as a participant of the ceremony. I wondered if these protestors use loudspeakers every year and whether the people of Hiroshima would actually tolerate this.

I caught sight of Ms. Yahata after the ceremony. I immediately called out to her, and she remembered who I was. “I lost my contact lenses, so I’m wearing glasses today,” she told me with a smile.

What? I thought she had worn glasses the last time we met, but then I realized she was now wearing glasses with a higher power than the pair she was wearing previously. I guess she usually wears contact lenses with a high power and glasses with a low power. That must be Ms. Yahata’s personal style.

“Do you have any water? I’ll give you some water,” she said, pulling a bottle of water from her bag and handing it to me. As a journalist attending the ceremony, I couldn’t accept water from Ms. Yahata, who was a guest at the ceremony. I politely declined as I had a bottle of water in my own bag, but she kept trying to hand me hers.

After exchanging a few words with Ms. Yahata and parting ways with her, I slightly regretted that I hadn’t accepted her water. She had really wanted to give me her water. By accepting her water and thanking her for it, I might have been able to exorcize some of her regrets and bring relief to the terror she had experienced 76 years ago.

I decided that I would go along with Ms. Yahata’s wishes if I ever have the chance to meet her again. I will visit Hiroshima again next summer.

Tags associated with this article