column 2 Yoko and Sadako: Children under the mushroom cloud

Introduction

In August 1945, the war took a drastic turn for the worse for Japan. The Japanese people were doing their best just to get by in the midst of a scorching Hiroshima summer. Like other cities in Japan, even the local children were unable to escape having their lives impacted by war, and clung to the small passing joys of their everyday lives. Thirteen-year-old Yoko Moriwaki loved her school sewing lessons, while two-year-old little Sadako Sasaki played with her elder brother Masahiro on the riverbanks near their house. The incident that occurred on the morning of August 6 instantly changed their lives forever.

1. August 5—A final diary entry Yoko Moriwaki was born in June 1932. Her father worked as an elementary music teacher, which led her to fall in love with piano, singing, and other forms of music. In April 1945, Yoko entered her dream school, the Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School. However, the war cast a dark shadow over her life there. The girls had to do farm work at the school to increase food production and build airraid shelters. They also worked to demolish buildings; dismantle standing buildings and homes to create firebreaks with the purpose of preventing the spread of fires caused by the air raids. The girls worked hard to fulfill their duties, despite their poor physical health due to malnutrition from the severe food shortages.

Yoko Moriwaki was born in June 1932. Her father worked as an elementary music teacher, which led her to fall in love with piano, singing, and other forms of music. In April 1945, Yoko entered her dream school, the Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School. However, the war cast a dark shadow over her life there. The girls had to do farm work at the school to increase food production and build airraid shelters. They also worked to demolish buildings; dismantle standing buildings and homes to create firebreaks with the purpose of preventing the spread of fires caused by the air raids. The girls worked hard to fulfill their duties, despite their poor physical health due to malnutrition from the severe food shortages.

Due to their military duties, their time for studying was limited, but the girls were able to capture small moments of joy and fun during wartime. Yoko’s diary describes her everyday life at school and at home in her beautiful handwriting. For example, she wrote about how her biology teacher always cracked jokes to make the class laugh; and she had fond memories of making a summer dress at the school sewing lessons with her school friends and practicing the famous song “Natsu wa Kinu (Summer has come)” with the choir. She wrote, “someday, we will all be mothers,” and “I worked hard because one day, I will have to take care of my own children” (Diary entry for May 2, 1945). When the girls studied how to take care of their little brothers and sisters, every one of them must have been imagining their future lives. Her diary goes on, “yesterday, my uncle came to visit us. Everyone was so happy to see him,” and “I wish we could live this way every day.” Her diary dated August 5, 1945 ends with the line, “starting tomorrow, we will work on the building demolition site.I will do  my best.” Yoko would never write in her diary again.

my best.” Yoko would never write in her diary again.

On the morning of Monday, August 6, Yoko cheerfully waved goodbye to her family and left her home on Miyajima Island. As always, she ran down the stone-paved stairs on the gentle slope in front of her house. She took the ferry and then a train to reach Dobashi (the place where her group was to meet). Shortly after 8:00 a.m., the 223 students from the girls’ school must have been busy preparing for building demolitions. At 8:15 a.m., there was suddenly a blinding flash overhead followed by a gigantic blast of heat and radiation all at once. Located only 700 meters from the hypocenter, without any shade or shelter, the girls were directly exposed to the A-bomb. Most of them died that day. Yoko herself was mortally wounded and sent to a relief station on the outskirts of Hiroshima, 10 kilometers from the city. There the girl—only thirteen—breathed her last breath while eagerly waiting for her mother to take her home. Yoko Moriwaki was just one of the approximately 7,200 mobilized students that died in the atomic bombing.

2. Wishing upon a thousand paper cranes

Sadako Sasaki was born in January 1943. On the morning of August 6, 1945, she was eating breakfast with her mother, grandmother, and elder brother—her father was absent because he was serving in the army. At 8:15 a.m., the atomic bomb struck the family at home in the Kusunoki-cho, 1.6 kilometers in the north-west from the hypocenter. All the family members survived without serious injury. Sadako was blown away by the blast, but she escaped from the experience seemingly without a scratch.

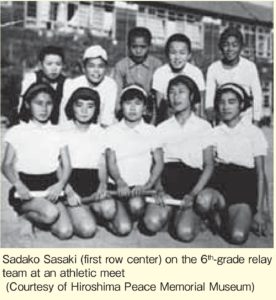

After the war, in April 1949, Sadako entered Noboricho elementary school.  She had always been a girl of steady character from younger age, and loved roses and music. She had good reflexes and in her 6th grade, she ran the anchor leg for the girls’ relay team at their athletic meet and helped them to win the championship. Sadako was a big fan of Hibari Misora, a popular female singer. Her dream was to become either a singer or a junior high school PE (physical education) teacher. Sadako was suddenly afflicted by illness ten years after the atomic bombing, in January 1955. Her doctor diagnosed her with lymphatic leukemia and one of the causes was the radiation from the A-bomb that she was exposed to at the age of two. The doctor gave Sadako just three to twelve months to live. Her parents grieved so deeply.

She had always been a girl of steady character from younger age, and loved roses and music. She had good reflexes and in her 6th grade, she ran the anchor leg for the girls’ relay team at their athletic meet and helped them to win the championship. Sadako was a big fan of Hibari Misora, a popular female singer. Her dream was to become either a singer or a junior high school PE (physical education) teacher. Sadako was suddenly afflicted by illness ten years after the atomic bombing, in January 1955. Her doctor diagnosed her with lymphatic leukemia and one of the causes was the radiation from the A-bomb that she was exposed to at the age of two. The doctor gave Sadako just three to twelve months to live. Her parents grieved so deeply.

Sadako was hospitalized on February 21 that year (1955) in the children’s ward at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. While she was there, she saw children die from late radiation effects, known as “atomic bomb disease.” Although she was not told that she had leukemia, she seemed to know that her disease was incurable. The treatment for leukemia at the time must have been extremely painful, since she had to be on powerful medications and get repeated blood transfusions. Sadako fought against the disease, never complaining about her pain and suffering. She tried hard not to make her parents worry.

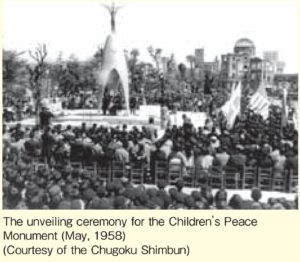

Around August 1955, Sadako heard an old Japanese tale that said a prayer would be granted to those who folded a thousand paper cranes. She was  inspired with singleminded purpose, and began folding paper cranes together with a girl who shared her sick room. She was always folding paper cranes, even while her family or friends were visiting her. She continued folding paper cranes to pray for her early recovery and her desire to live. Unfortunately, her wish did not come true. Sadako Sasaki passed away on October 25, after eight months of fighting her cancer. Her short life was over after just twelve years. Upon her death, children in Hiroshima and other parts of Japan began a campaign to raise funds to build a memorial monument to mourn the souls of all children who died from the atomic bomb and to build lasting peace. In May 1958, Children’s PeaceMonument was built in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

inspired with singleminded purpose, and began folding paper cranes together with a girl who shared her sick room. She was always folding paper cranes, even while her family or friends were visiting her. She continued folding paper cranes to pray for her early recovery and her desire to live. Unfortunately, her wish did not come true. Sadako Sasaki passed away on October 25, after eight months of fighting her cancer. Her short life was over after just twelve years. Upon her death, children in Hiroshima and other parts of Japan began a campaign to raise funds to build a memorial monument to mourn the souls of all children who died from the atomic bomb and to build lasting peace. In May 1958, Children’s PeaceMonument was built in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Conclusion

The Hundreds, thousands of people died in great agony under the mushroom cloud, regardless of their age, gender, occupation and nationality. A single bomb robbed thousands of children of their lives and futures. Many of them left behind no physical remains or personal effects. Often, those who barely survived became orphans, losing all of their family members and friends. Few survived the war without severe and lasting emotional or physical scars.

The diary that Yoko left behind was published in 1996 in Japan by her elder brother, Koji Hosokawa. In 2013, the diary was translated in English. Sadako’s story was introduced to the wider world by Robert Jungk, Karl Bruckner, and Eleanor Coerr. In 2013, Sadako’s brother Masahiro published a biography of Sadako. As they carry on their lives with the chagrins of their sisters and pains as bereaved families, the brothers of Yoko and Sadako continue to speak out about their sisters with the hope that younger generations will take what happened in Hiroshima to heart, think about it, remember it, and respect how precious their everyday lives are while respecting one another.

(Hitoshi Nagai)

Inquiries about this page

Hiroshima Prefectural Office

Street address:10-52, Motomachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi, Hiroshima-ken, 730-8511

Tel:+81-(0)82-228-2111