A remedy for division: What I learned from Hiro-shima

HORI Jun

◆ “Courage, action, and love”

I’m writing this manuscript while looking up at the Atomic Bomb Dome and the sky stretching out beyond it. This sky should be connected as one, but the world is only becoming more divided.

Division creates ostracism, and ostracism eventually becomes violence. When nations are swallowed by violence, war begins. There is no mercy. The gears of cannibalism don’t stop turning until one side runs out of strength. The weak are forced to bear the burden of sadness, and people continue to suffer with the after-effects for generations. And the corrosion of society continues.

I know we’ve repeated the trial and error countless times, telling ourselves we can’t mess up again. We’ve called for disparity adjustment, international cooperation, and sustainable social reforms. We’ve desperately broadcast these messages to keep them from becoming empty echoes.

It is also true that we have built a history we can look back on proudly, one of relentless hard work in which citizens have been the main actors.

But even so, now our way is blocked by baffling and powerful “societal ills.” And they are everywhere. I have come to realize how irresponsible the phrase “20th century relic” was, and what a privileged place it came from. The world has been injured. The threat of nuclear war is before us. This is what we get for pretending not to see it.

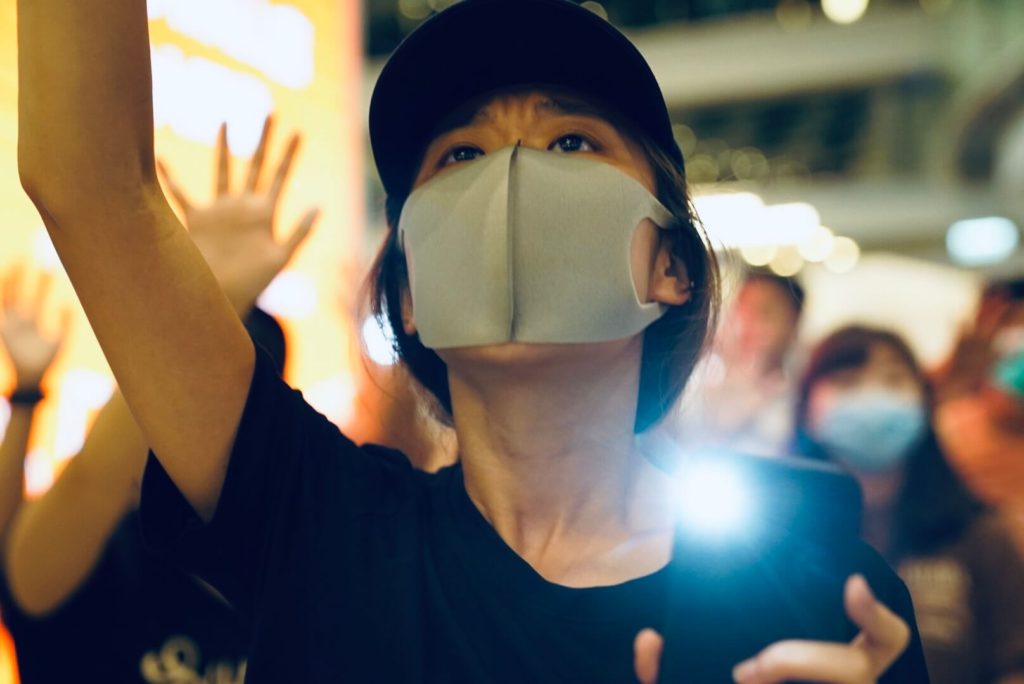

For the past 10 years, I have been visiting divided places and trying to find ways to heal them.

Palestine, Cambodia, Sudan, Syrian refugee camps, South Korea, North Korea, Hong Kong, China, North America, Europe, and Japan. These places all have different backgrounds with things like dictatorship, war, disparities, poverty, ethnic groups, and religion. I have traveled while doing interviews to clarify who caused the division and what the prescription might be to treat it.

When authoritarianism loses to economics, our “freedom and democracy” crumbles from beneath our feet. And when “freedom and democracy” lose to greed, a new kind of authoritarianism is born.

Authoritarian states don’t necessarily take from us. I have realized that we sometimes lose what’s important to us by offering it up ourselves.

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” As in this philosopher’s quote, what I thought were my good actions eventually brought about major tragedy. I must be aware of this. I must know history, expose myself to different values, and choose my own future. I now look back on my own history and see how my ignorance, disinterest, and stereotypical thinking isolated and hurt people who were struggling to speak up.

But I will not give up. I am now supported by the belief that I don’t have to give up. I have not lost the willpower to continue standing up.

One summer 10 years ago, I received that strength from a certain person in California.

Sasamori Keiko was 89 years old. 77 years prior on August 6th, she was working as a student mobilizer at Tsurumi Bridge West around 1.5 kilometers from ground zero when the atomic bomb hit. She sustained large burns on one quarter of her body. She gradually recovered from her wounds under her mother’s frantic care, but her fingers stuck together and it was hard to open her mouth. At the time, there were many women like Ms. Sasamori who had been severely burned and had keloid scars remaining on their faces. In 1955, 25 of these women were invited to the United States to receive surgery for functional recovery. They were given the option to be fostered and live as Americans. Ms. Sasamori was one of these 25 “atomic bomb girls.”

I met Ms. Sasamori in the US in 2012 and had the opportunity to speak with her in her home. It was at this time that the grandson of one of the crew members of the “Enola Gay” bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima visited Ms. Sasamori for the first time.

This was a young man who cared about Japan to the extent he had volunteered in towns that were damaged in the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. When I asked why he wanted to meet Ms. Sasamori, he muttered, “I wanted to talk to her. Just talk. I figured I would start there.”

Ms. Sasamori welcomed him into her home like an old friend. Sitting at the dining table, she took his hand and said, “Your heart. This heart you have. Believe in yourself. I’m sure it was a tough decision to come here. I want you to continue having conversations like this, continue learning.” As Ms. Sasamori continued smiling and speaking, he looked straight into her eyes and nodded repeatedly. My hands shook as I held the camera. They talked for around an hour. The words of peace Ms. Sasamori spoke to him at that time are what sustain me now.

“When people ask me if we can achieve peace, I say we definitely can, without a doubt. To do that, we need courage,

action, and then love. We need all three of these things. With only courage and action, sometimes war can happen. With only courage and love, we might only say nice words and nothing more. But if we combine all three, we can absolutely achieve peace. That’s what I think.”

Seeing those two hug at the end and promise to meet again empowered me to believe in my own heart.

It’s been 10 years since then. War has broken out between Ukraine and Russia, and I see the threat of nuclear war looming before me. To overcome my fear, I visited some friends to hear the words of atomic bomb survivors once again.

◆ “I’m just doing what I can”: Hachidori

A two minute walk from the Peace Memorial Park, on the second floor of a multi-tenant building is the “Social Book Cafe Hachidori-sha.” When I climb the dark staircase, knock on the small door and open it, I find a space with a soft atmosphere filled with wooden chairs, desks, and shelves. With a “create it yourself” concept, the cafe was crowd funded and opened in July 2017 as a space for the DIY trend.

On every day with a “6” in it, atomic bomb survivors and participants gather around a table for an event called “Talk with storytellers on days with 6!” Over 5 years, around 2000 people have come to hear survivors’ voices and exchange opinions.

The day I visited, a variety of people including university students, office workers, and children’s book authors had come to Hachidori-sha to hear directly about what had happened that day.

“This didn’t happen in a monochrome world. The line of history extends to where we are now.”

This is what the cafe owner, 43 year-old Abiko Erika, says to the participants. When she was 23, she traveled around the world on Peace Boat.

She met a Palestinian named Zaher who was around her age, and heard about how overwhelming violence can take away people’s right to live. How in reality, some people could not have such a simple thing as living in peace with their families. Until that day, many people had lost their lives without her knowing. She says that when she realized this truth, she began to wonder if she was one of the perpetrators.

“Wars were happening because of things I didn’t know about, so I wanted to know them, and to think about them, and to do something. Peace is a far-off reality, but if I give up, if even one person gives up, that makes the world worse. So I don’t want to give up.”

Hiroshima has plenty of places like the Peace Memorial Museum and the atomic bomb buildings where history is inputted. But one reason Ms. Abiko started Hachidori-sha was because there were hardly any places for output. Places where people could socialize, discuss, and not give up their longing for peace. Mutual encouragement is the driving force that has sustained the cafe.

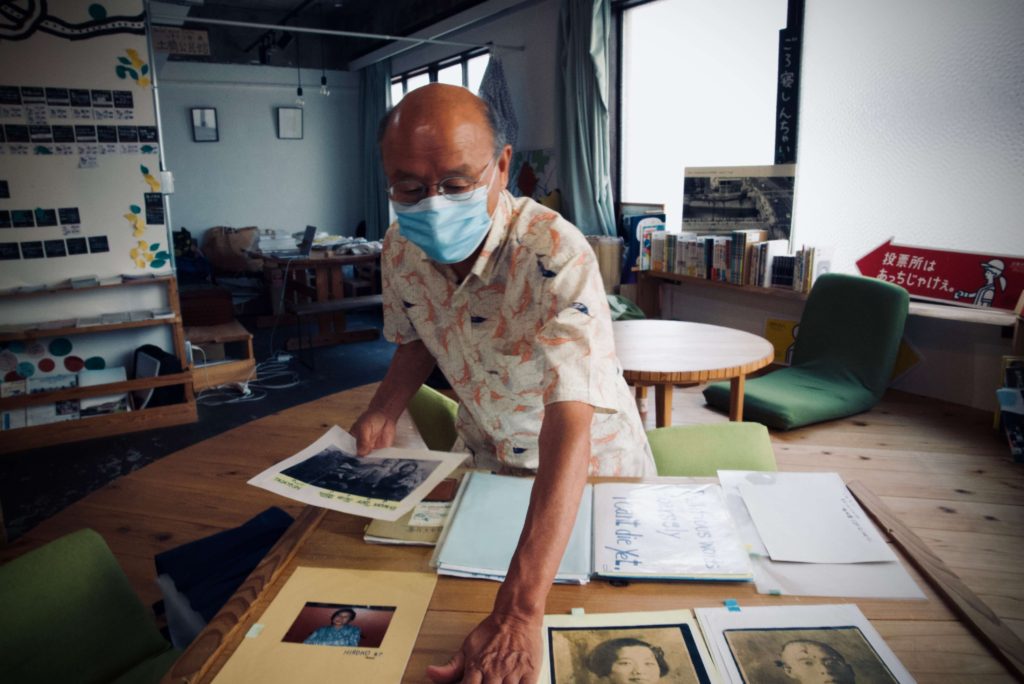

Drawn to Ms. Abiko’s ambitions, one man comes to testify on almost every day with a “6” in it.

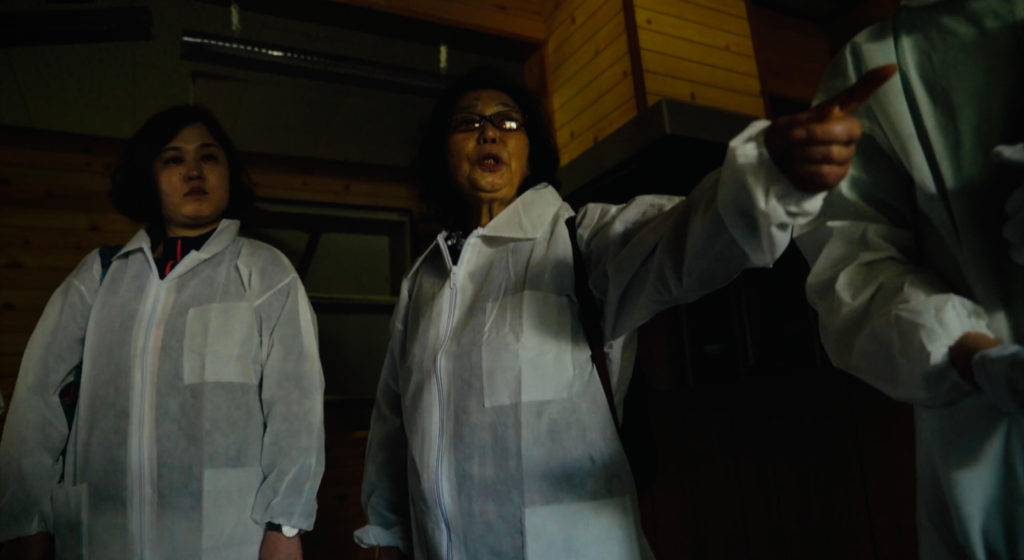

Futagawa Kazuhiko is 76 years old. He was in his mother’s womb the day the bomb was dropped, so although he didn’t experience the nuclear disaster directly, he is among the youngest of the atomic bomb survivors. He has been actively sharing his experience with his family’s suffering and other obstacles along with other fetal survivors. “My dad and sister both died in the bombing. My mom and two brothers survived, but none of them talked about their atomic bomb experience. So I’m here today because I feel like I need to talk about it as a representative of my family,” he says to the participants, spreading out maps and photos from that time while carefully sharing his story.

Mr. Futagawa’s father Ichie was 47 years old. He was working at the Zaimokucho Post Office, which was where the Peace Memorial Museum is now. His sister Sachiko was 13 at the time. She was evacuating a building around 800 meters from ground zero in Zakobacho when the bomb hit. His mother Hiroko, who was pregnant with him at the time, was near their home in Yagacho around 3.8 kilometers from ground zero, and was not injured. Hiroko put a futon in a large wagon and went into the city center to look for her husband and daughter, but she couldn’t find them. Then Kazuhiko was born in April of the following year. He began to wonder about the atomic bombing as he got older, but he says Hiroko told him almost nothing.

What sorts of thoughts did Hiroko live with? He got a glimpse of that 14 years after Hiroko died at age 87. That was when he suddenly found a green blouse his sister Sachiko used to wear in the back of his mother’s old dresser. It was carefully wrapped in white Japanese paper and put away so no one would find it. The only keepsake from his sister. Her school name tag was sewn onto the left chest side. Seeing this, Mr. Futagawa was overcome with tears.

“Why didn’t she tell me? She kept her feelings bottled up and just lived with the pain on her own. This is how cruel nuclear bombing is. Did she keep quiet because she didn’t want me to worry about having been exposed? Maybe it was out of love. She got through it all on her own.” With that thought, he just couldn’t stop crying. He had to tell people. That was the year he did his first newspaper interview.

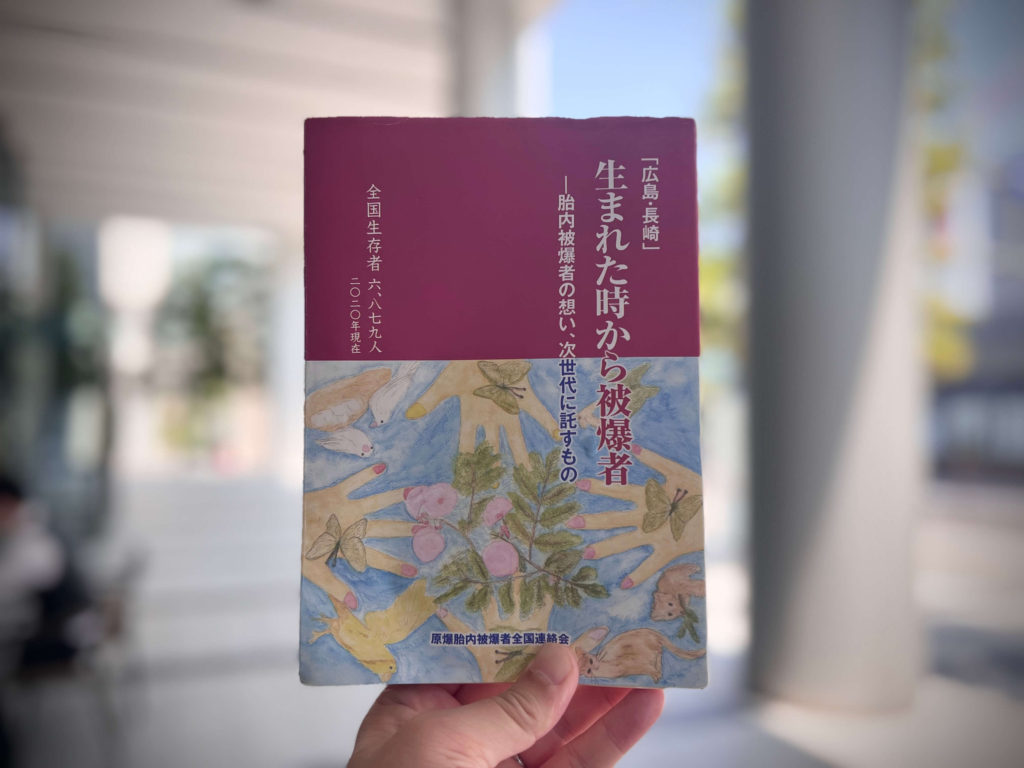

Mr. Futagawa is also a facilitator for the “Fetal Atomic Bomb Survivors National Liaison Group” made up of fetal atomic bomb survivors. In 2020, he contacted fetal survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki now living around Japan to share their experiences, which he compiled in a memorandum. The group published it as a book titled, “Survivors from birth: Passing on the thoughts of fetal atomic bomb survivors to the next generation. “My peers sometimes tell me, ‘You like this, huh Futagawa?’ They mean my interviews and media appearances. People think, ‘There are atomic bomb survivors in Hiroshima, but there are none in my family.’ They just don’t care. It can’t be like that,” he said to explain his reasons for sharing.

Mr. Futagawa also shared a perspective that’s surprising coming from him. “People should know that Hiroshima was not only a bombing site, but also the largest military city in Japan. They were secretly creating poisonous gas weapons on Okunoshima Island. We were not only victims, but also perpetrators. We need to have that balance when sharing this with the world. People in Southeast Asia won’t be sympathetic hearing only about our victimhood.” This balance is essential to make definite progress toward peace. I thought so, too. We can remedy division by knowing our history as victims while also facing the aggression caused by the apparatus of war.

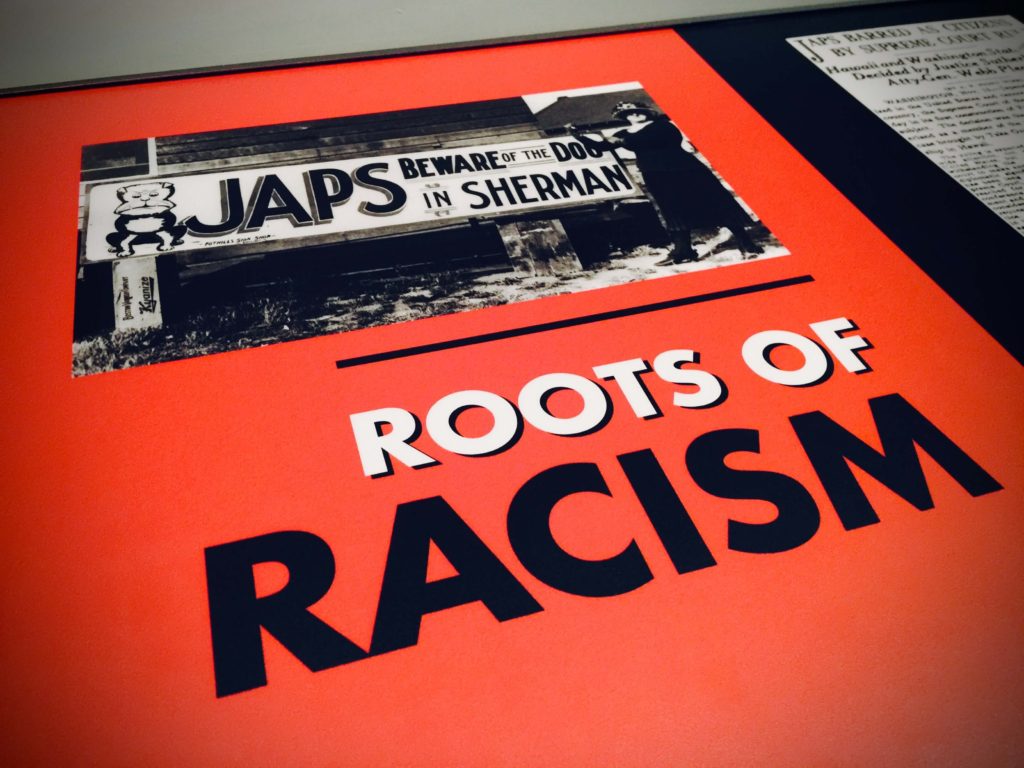

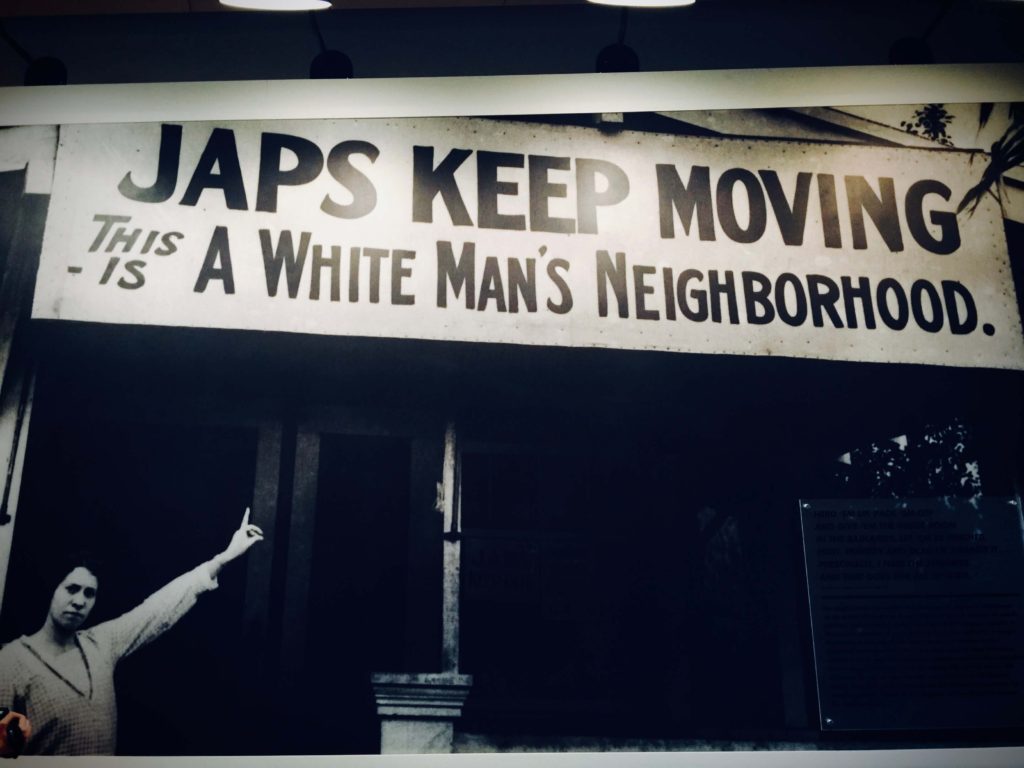

Listening to Mr. Futagawa’s story, I remembered the time I reported on the Manzanar Internment Camp in California.

This facility to segregate Japanese people was built on desolate land in the middle of the desert, where there was nowhere to escape to. The original building has been preserved and is now a national park with a museum.

The theme of the exhibition is “the history of discrimination.” Photo and video footage shows the discrimination and ostracism many US citizens participated in after the war began. It is an attempt to explore the value of universal peace by facing the history of discrimination head on. Coming to terms with the harm your own people have inflicted can be an austere experience that takes courage.

This was one site where I felt the depths of the heart of a democratic nation. And now, I was deeply moved seeing Mr. Futagawa before me speaking about the harm Japan caused during the war. I felt the power of his words because they showed an attempt to overcome antagonism and build a future where we work together with empathy.

◆ I planted a seed, then a flower bloomed

What is peace? The answer to that question is simple, but also the start of a never-ending quest.

When I visited Palestine in 2016, there’s something the locals taught me. Called a “prison without a ceiling,” the Gaza region is surrounded by walls and fences built by the Israeli government to isolate the people. When I said to the Palestinian man accompanying me for interviews, “I hope there will be peace soon,” he asked, “Whose peace are you talking about? Both we Palestinians and the Israelis hope for peace, yet the conflict continues. So whose peace are you talking about? That’s important.”

It’s true that the visions of “peace” each side aims for don’t overlap so easily. To some people peace means quietly reading a book, while to others it means having the freedom for vigorous activity. If we have different values and different visions of the ideal future we want to see, it’s quite difficult for the two to co-exist. That’s why we need to have dialogue to verify the definitions of each other’s terms. It may be troublesome having to ask about every little thing, but there is no mistaking the fact that self-centered assumptions and prejudices can lead to misunderstandings, disagreements, aggression and violence.

One man has been asking large numbers of children the question, “What is peace to you?”

To meet that man, I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum after 1 p.m. on a Thursday afternoon.

The sky was an endlessly deep, clear blue. I made my way to the museum while seeking shade to avoid the scorching rays of the sun. Lines of elementary school students on educational visits or field trips stood in the plaza in front of the museum. Judging by the conversations of the teachers, the students seemed to be from the Kyushu and Kansai regions.

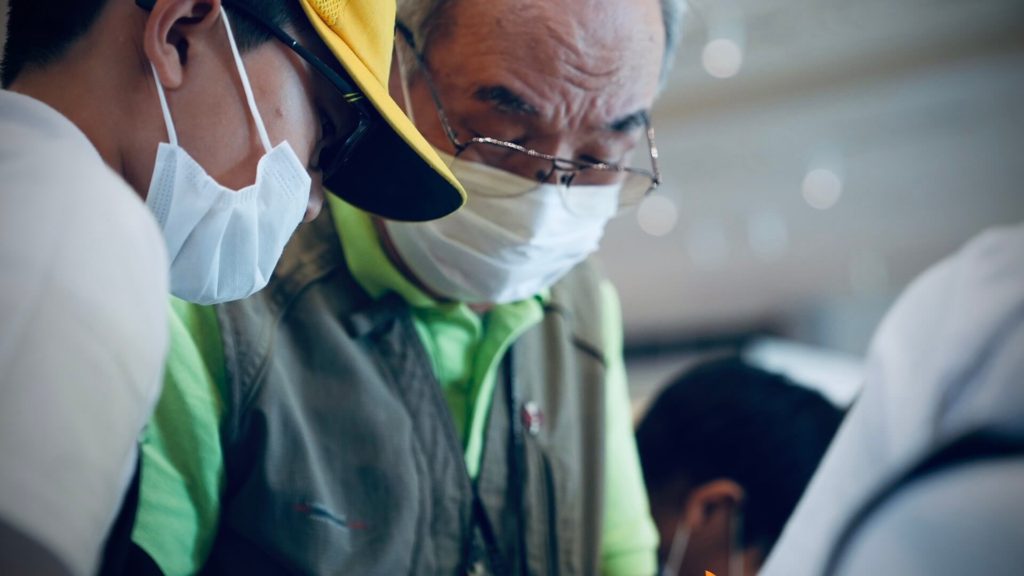

I went inside the entrance doors and looked to the right and left of the reception window. A man stood in front of a desk by the exhibition area, folding paper cranes. Children would approach to give him more origami paper, and he would hand over the finished cranes one at a time while quietly speaking to the children.

Ito Masao is 81 years old. At age 4 and a half, he was in the Kogo region around 3.5 kilometers from ground zero when the atomic bomb hit. He was too young at the time to remember much now. But he says there is once scene still burned into his memory so vividly he can’t forget it.

That day, Mr. Ito was riding a tricycle in front of his house. It was 8:15. He thought he saw a blue light cutting across the sky from east to west, and then he was flung by the blast along with his tricycle. He fainted momentarily, but quickly regained consciousness and returned to the house crying. His mother Kimie frantically rushed toward him at the entrance. “You don’t have to take off your sandals, leave them on,” she said, so he fled into the house with his sandals on. There was glass everywhere, and it was very difficult to walk. Underneath a tatami mat was a basement. It was a bomb shelter. They took shelter there for a while and were able to avoid getting directly hit by the “black rain.” His father Tatsuo was recruited to a rescue team by the military, and headed into the burning city in a truck. He had a 12 year-old brother and a 10 year-old sister, but his sister was never found, and his brother sustained burn injuries and passed away on August 29th, 20 days after the bombing.

“The memory I can’t forget from August 6th is all the people running away. We let some of those people rest in our house, but they died one after another. It was August, and it was hot. If you left someone who had died for even one night, immediately the body would start to rot. I saw those dead people getting stacked up like a pyramid in an empty lot next to the house, and then getting burnt.

Even burning just one body creates a horrible stench, so if you’re burning ten of them, the smell is so bad it can’t be expressed in words. That situation went on for almost a week. I was a small child, but that scene is burned into my eyes, the smell is burned into my nose, and I remember it whenever I talk about it.”

Mr. Ito started folding paper cranes in this exhibition space to help collect signatures for the early enforcement of the “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” adopted by the UN in 2017. He says he folded a crane for each person who signed and presented it to them right there. And this is the conversation he had with the children as he taught them how to fold cranes.

“What was it like, seeing the museum?” “It was really terrible, and showed us how important peace is.” “What is peace?” “It’s when there’s no war, and everyone in the world gets along.” “Right. I’ve been trying my best to create a world without war, and there’s been no war in Japan for 70 years, but there have been wars in other countries. When you become leaders in Japan in the future, make sure you don’t ever start a war, okay?” “Okay.”

Mr. Ito and the others collected 3,000 signatures here, and handed out a corresponding number of paper cranes. Perhaps out of shyness, the children were hesitant, but they gave their answers confidently.

Why does Mr. Ito continue standing here? When I candidly asked him the reason, this was his reply.

“What really moved me about being here is when I planted a seed in a child 10 years ago, and then that child became a mother and brought her own child here. She said, ‘I came to Hiroshima on a field trip and heard your story, but my child won’t have a field trip to Hiroshima or any education about peace, so I brought my child here.’ And I was so happy. It made me think that the seeds we’d planted weren’t in vain. Not all of them will sprout, but one by one many eventually will, and I’m just full of hope that we can trust these children to at least create a world without nuclear weapons someday.”

Mr. Ito also says, “Even if you can’t do much, you’re not powerless.” It’s because the atomic bomb survivors have passed on the history of that day for the past 77 years, holding hands with one person at a time, that we are where we are today. They never gave up.

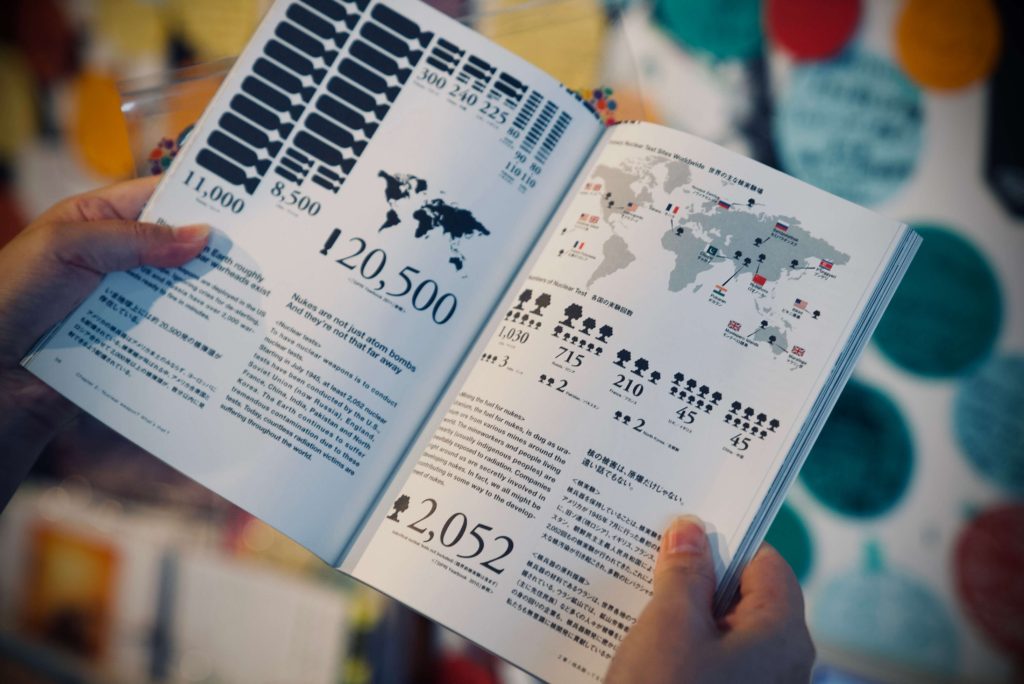

A meeting of signatory nations for the “Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons” was held in Vienna for the first time this year. The Japanese government did not participate even as an observer, for the stated purpose of “mediating between nuclear and non-nuclear states.” But representatives from Germany, Holland, and Norway, which are protected under the United States’ “nuclear umbrella,” participated as observers and gave speeches. The German representative once again declared that Germany could not participate in the treaty, but also said, “We completely share the goal of ‘a world without nuclear weapons,’ and we hope to continue having dialogue and discussions to move toward this common goal,” demonstrating a head-on stance domestically and abroad. The world is watching what happens in Japan. I am also watching to see if we have courage, action, and love. From Hiroshima, many are watching.

Tags associated with this article