Hiroshima Report 2024(6) Diminishing the Roles and Significance of Nuclear Weapons in National Security Strategies and Policies

A) The current status of the roles and significance of nuclear weapons

In the latter half of the 2010s, as great power and geopolitical competitions have become more intense, nuclear-armed states have reaffirmed the roles and significance of their nuclear weapons within their national security. While no nuclear-armed states and their allies have announced new nuclear strategies or policies in 2023, there is an observable trend of these states increasingly relying on nuclear deterrence in response to ongoing and complex security challenges. Among those countries, Russia and North Korea continued to notably intensify their rhetoric on the strategic value of their nuclear arsenals throughout 2023, underscoring a pronounced emphasis on their nuclear capabilities.

While continuing its invasion of Ukraine, Russia repeated its nuclear intimidation in 2023. In January, Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of Russia Dmitry Medvedev said, “The defeat of a nuclear power in a conventional war may trigger a nuclear war.”143 In March, he also threatened a possible nuclear strike, saying that if the Ukrainian military attacked to retake the Crimean Peninsula, currently under effectively Russian control, “it would clearly be grounds to use all means of defense, including those specified in the nuclear deterrence doctrine.”144 Furthermore, in July, he stated, “In general, any war, even a world war, can be ended very quickly. Either if a peace treaty is signed, or if you do what the Americans did in 1945, when they used their nuclear weapons and bombed two Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They, indeed, then curtailed the military campaign. The price is the life of almost 300,000 civilians.”145 Shortly thereafter, he warned: “Just imagine that the offensive … in tandem with NATO, succeeded and ended up with part of our land being taken away. Then we would have to use nuclear weapons by virtue of the stipulations of the Russian Presidential Decree.”146

Russia’s nuclear intimidation was strongly condemned at the 2023 NPT PrepCom, mainly by Western countries. For instance, the United States stated, “Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine tragically continues, as do Russia’s irresponsible nuclear rhetoric. … Russia’s actions are hardly a side show, unrelated to the Treaty and its political process; instead, they strike at the heart of the NPT’s bargains, and at the system of nuclear restraint it helps make possible.”147 Japan also argued: “[T]he very core values of the NPT regime have been seriously threatened and challenged by the words and actions of the Russian Federation in the course of its aggression against Ukraine, which Japan strongly condemns. It is completely inacceptable that a nuclear weapon state imposes its political will upon a non-nuclear weapon state with a thinly veiled threat of use of nuclear weapons.”148

Russia responded by stating the following:

At this stage the continued possession of nuclear weapons is for our country the only possible response to certain external threats. The Ukrainian crisis provoked and fueled by the West has confirmed the validity of our concerns. … Under these circumstances, further reductions in our country’s nuclear weapons would not only dramatically decrease its security, but would actually turn the idea of large-scale aggression against Russia into a very realistic option for NATO countries, which have a significant advantage in conventional weapons.149

On October 25, Russia conducted a large-scale retaliatory nuclear strike exercise, launching Yars ICBM, Sineva SLBM, and air-launched cruise missiles. In December, President Putin stated, “Given the changing nature of military threats and the emergence of new military and political risks, the role of the nuclear triad, which ensures the balance of power, the strategic balance of power in the world, has significantly increased.”150

North Korea reiterated in 2023 that it would expand the role of nuclear weapons in its national security, and actively conducted missile tests and drills of various types.

A report of the Enlarged Plenary Meeting of the Workers’ Party of the Korea Central Committee held on December 26-31, 2022 was published in the KCNA on January 1, 2023. The report stated that, with regard to nuclear strategy, North Korea’s “nuclear force considers it as the first mission to deter war and safeguard peace and stability and, however, if it fails to deter, it will carry out the second mission, which will not be for defense.” It also mentioned that “a task was raised to develop another ICBM system whose main mission is quick nuclear counterstrike,” which is likely to mean solid-fuel ICBMs. Furthermore, the report stated, “Now that the south Korean puppet forces who designated the DPRK as their ‘principal army’ and openly trumpet about ‘preparations for war’ have assumed our undoubted enemy, it highlights the importance and necessity of a mass-producing of tactical nuclear weapons and calls for an exponential increase of the country’s nuclear arsenal, the report said, clarifying the epochal strategy of the development of nuclear force and national defence for 2023 with this as a main orientation.”151

The North Korea’s nuclear posture, consisting of the two missions described above, was repeatedly mentioned. On March 9, Chairman Kim Jong Un emphasized: “the [Hwasong artillery unit] should be strictly prepared for the greatest perfection in carrying out the two strategic missions, that is, first to deter war and second to take the initiative in war, by steadily intensifying various simulated drills for real war in a diverse way in different situations.”152 At the “combined tactical drill simulating a nuclear counterattack by the units for the operation of tactical nukes” on March 18-19, Chairman Kim said that North Korea “cannot actually deter a war with the mere fact that it is a nuclear weapons state,” and emphasized that “it is possible to fulfill the important strategic mission of war deterrence and reliably defend the sovereignty of the country … only when the nuclear force is perfected as a means actually capable of mounting an attack on the enemy and its nuclear attack posture for prompt and accurate activation is rounded off to always strike fear into the enemy.”153

In June, the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) published a report that was prepared by the National Intelligence Council (NIC) in January 2023. The report, titled “North Korea: Scenarios for Leveraging Nuclear Weapons Through 2030,” detailed various potential uses of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, categorizing them into coercive, offensive, and defensive objectives. Notably, the report emphasized the likelihood of North Korea employing its nuclear weapons for coercive purposes as the most probable scenario. It also stated, “North Korea most likely will continue to use its nuclear weapons status to support coercive diplomacy, and almost certainly will consider increasingly risky coercive actions as the quality and quantity of its nuclear and ballistic missile arsenal grows.”154

Concerns have been raised regarding China’s rapid expansion of its nuclear capabilities and the potential increase in the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy. However, China has consistently denied these allegations. It stated:

China has always pursued a nuclear strategy of self-defense, and undertakes not to be the first to use nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and unconditionally commits itself not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon States or nuclear-weapon-free-zones. No matter how the international situation changes, China will always maintain its nuclear force at the minimum level required for national security, and will not seek nuclear parity or engage in a nuclear arms race with any nuclear-weapon State. China does not provide nuclear umbrella and does not deploy nuclear weapons abroad.155

B) Commitment to no first use, “sole purpose,” and related doctrines

In 2023, no nuclear-armed state changed or altered its policy regarding no first use (NFU) or the “sole purpose” of nuclear weapons. Among the NWS, China remains the only one to have officially declared an NFU policy, and it reaffirmed this commitment in 2023. The other four NWS have declined to embrace NFU or “sole purpose” policies. China has advocated that all NWS should unconditionally commit to NFU of nuclear weapons, and negotiate and conclude international legal instruments toward this end. While the United States has argued that there is some ambiguity about conditions where Beijing’s NFU policy would no longer apply, China contested these claims.

Regarding the other nuclear-armed states, India maintains an NFU policy despite reserving the option of nuclear retaliation in response to a major biological or chemical attack. Meanwhile, Pakistan, which has developed short-range nuclear weapons to counter the “Cold Start doctrine” developed by the Indian Army, does not exclude the possibility of first use of nuclear weapons against an opponent’s conventional attack.

North Korea, in its law on “Policy on Nuclear Forces” enacted in September 2022, indicated that there is a possibility of first use of its nuclear weapons.156 In recent years, North Korean leaders have repeatedly and strongly mentioned the possibility of nuclear first use.

C) Negative security assurances

No NWS significantly changed its negative security assurance (NSA) policy in 2023. China is the only NWS that has declared an unconditional NSA for NNWS, while the other NWS add some conditions in their NSA policies.

The United Kingdom and the United States declared they would not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against NNWS that are parties to the NPT and in compliance with their non-proliferation obligations. The U.K.’s additional condition, as stated in its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy is that: “[W]e reserve the right to review this assurance if the future threat of weapons of mass destruction, such as chemical and biological capabilities, or emerging technologies that could have a comparable impact, makes it necessary.”157 The United States in its 2022 NPR reaffirmed its above-mentioned declaration.

In 2015, France slightly modified its NSA commitment, which stated that: “France will not use nuclear weapons against states not armed with them that are signatories of the NPT and that respect their international obligations for non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.”158 The condition added in 2015 was that its commitment does not “affect the right to self-defence as enshrined in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.”159

Russia upholds a unilateral NSA under which it will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against the NNWS parties to the NPT, except in cases where Russia or its allies are invaded or attacked by a NNWS in cooperation with other NWS. Western countries have condemned Russia, claiming that its invasion of Ukraine, accompanied by nuclear intimidations, contravenes both the NSA and the Budapest Memorandum of Understanding that Russia signed with Ukraine and others in 1994. However, Russia has insisted that it has not threatened Ukraine with the use of nuclear weapons.160

As written in the previous Hiroshima Reports, while one purpose of the NSAs provided by NWS to NNWS is to alleviate the imbalance of rights and obligations between NWS and NNWS under the NPT, India, Pakistan and North Korea have also offered NSAs to NNWS. None of these countries significantly changed their NSA policies in 2023. India declared that it would not use nuclear weapons against NNWS, with the exception that “in the event of a major attack against India, or Indian forces anywhere, by biological or chemical weapons, India will retain the option of retaliating with nuclear weapons.” Pakistan has declared an unconditional NSA. In addition, North Korea stipulated in its law on Policy on Nuclear Weapons in 2022 that it “shall neither threaten non-nuclear weapons states with its nuclear weapons nor use nuclear weapons against them unless they join aggression or attack against the DPRK in collusion with other nuclear weapons states.”

Apart from the protocols to nuclear-weapon-free zone (NWFZ) treaties, NWS have not provided legally binding NSAs. The NAM countries reiterated their argument at the NPT PrepCom that: “[T]he Group stresses that the urgent negotiations on the provision of effective, unconditional, non-discriminatory, irrevocable, universal and legally binding security assurances by all the nuclear-weapon States to all non-nuclear weapon States parties to the Treaty against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons under all circumstances should also be pursued as a matter of priority and without further delay.”161 China has stated that it supports the early commencement of substantive work toward concluding an international legal instrument on NSAs.162 However, the other four NWS have been consistently reluctant to pursue their codification.163

At the 2023 UNGA, a resolution titled “Conclusion of effective international arrangements to assure non-nuclear-weapon States against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons” was adopted. The resolution “[r]eaffirms the urgent need to reach an early agreement on effective international arrangements to assure non-nuclear-weapon States against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons.”164 The voting behavior of countries surveyed in this project on this resolution is as follows:

➢ 123 in favor (Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria and others); 0 against; 62 abstentions (Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Israel, South Korea, North Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and others)

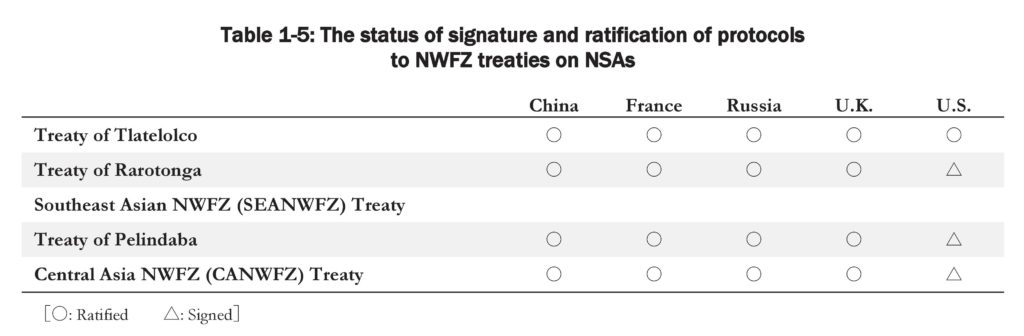

D) Signing and ratifying the protocols of the treaties on nuclear-weapon-free zones

The protocols to the NWFZ treaties include the provision of legally binding NSAs. However, as of the end of 2023, only the Protocol of the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (the Treaty of Tlatelolco) has been ratified by all NWS, as shown in Table 1-5. No new progress regarding additional ratifications by NWS was made in 2023.

Regarding the Protocol to the Southeast Asia NWFZ (SEANWFZ) Treaty (Bangkok Treaty), which has not been signed by any of the five NWS, the Executive Committee of the SEANWFZ Commission stated at the NPT PrepCom, “[I]t is continuing to explore the possibility of allowing individual NWS which are willing to sign and ratify the Protocol to the SEANWFZ Treaty without reservations and provide prior formal assurance of this commitment in writing to go ahead with the signing.”165 In July, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi told that the ASEAN will review the points of the treaty’s protocol in order to pave an easier way for the NWS to sign and ratify it.166 The five NWS have expressed their intention to sign the protocol, and it has been reiterated that consultations between the parties to the treaty and the five NWS are continuing. However, it is unclear how far the consultations have progressed.

Some NWS have added interpretations—which are substantially reservations—to the protocols to the NWFZ treaties when signing or ratifying them. The NAM and NAC, as well as states parties to the NWFZ treaties, have called for the withdrawal of any related reservations or unilateral interpretative declarations that are incompatible with the object and purpose of such treaties. For instance, the NAM countries argued, “[T]he Group strongly calls for the withdrawal of any related reservations or unilateral interpretative declarations that are incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaties to establish nuclear-weapon-free zones.”167 The Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL) also stated, “[It] has been seeking to establish a dialogue mechanism with these States to find mutually agreed solution to this issue. We hope that this PrepCom will serve as a platform for further discussions on this matter.”168

However, it seems unlikely that any NWS except China will accept such a request. Russia said at the NPT PrepCom, “[Its] reservations in no way affect the interests of States that intend to strictly adhere to their obligations under a relevant treaty establishing a NWFZ. They are merely a tool to ensure that NWFZ States comply with the provisions of the agreements they concluded.”169 The United States also stated, “Concerning U.S. -interpretative statements made in connection with ratification of those zone protocols, we wish to make clear that none are or would be inconsistent with the object and purpose of those treaties and their associated protocols.”170

E) Relying on extended nuclear deterrence

Russia and Belarus

On March 25, 2023, Russian President Putin announced that Moscow would station its tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus. He stated that Russia would complete construction of storage facilities for these weapons in Belarus on July 1. President Putin emphasized that this deployment would not violate the nuclear nonproliferation regime, as the control over these nuclear weapons would remain with Russia and not be transferred to Belarus. He drew a parallel by mentioning the deployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in NATO countries for decades.171 President Putin also disclosed that Russia had already transferred the nuclear-capable Iskander SRBMs and helped to upgrade 10 Belarusian aircraft to make them capable of carrying nuclear weapons.172

On May 25, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko announced that the process of transferring tactical nuclear weapons from Russia to Belarus had commenced. This move followed the signing of bilateral documents between two countries, permitting the placement of Russian tactical nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory.173 In December, President Lukashenko revealed that Russia had completed its shipments of tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus in October 2023.174

Throughout this period, President Lukashenko made several assertive statements on this issue. For instance, he suggested in May that countries willing “to join the Union State of Russia and Belarus” would be granted access to nuclear weapons.175 On June 13, he went further, warning that he would not hesitate to order their use in the event of an aggressive act against Belarus.176 However, Russia has consistently clarified that Russia retains the authority for the control and use of its nuclear weapons stationed in Belarus.177

NATO

Currently, it is estimated that the United States deploys approximately 100 B-61 nuclear gravity bombs in five NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey), and maintains nuclear sharing arrangements with them. NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) also supports the U.S. extended nuclear deterrence.

In the NATO Strategic Concept adopted in June 2022, there was a heightened emphasis on the role of nuclear deterrence compared to the previous version adopted in 2010, particularly concerning (extended) nuclear deterrence.178 In 2023, NATO members reaffirmed the significance of extended nuclear deterrence for NATO’s security strategy. For example, Germany in its National Security Strategy published in June stated that “[a]s long as nuclear weapons exist, maintaining credible nuclear deterrence is essential for NATO and for European security.”179 Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki reiterated his country’s willingness to participate in the NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements in the form of accepting U.S. nuclear weapons into Poland.180 There was no indication that the United States was considering this.

In October 2023, the annual NATO nuclear weapons exercise “Steadfast Noon” was held with up to 60 aircraft, including fighters, surveillance aircrafts and U.S. B52 strategic bombers from 13 of the NATO’s 31 member states.

Regarding Sweden which has applied to join NATO, its Foreign Minister Tobias Billström said, “Sweden is joining NATO without reservations. However, like the other Nordic countries, we do not foresee having nuclear weapons on our own territory in peacetime.”181

Indo-Pacific Region

While no U.S. nuclear weapon is deployed outside American territory, except in the NATO countries mentioned above, the United States has established consultative mechanisms on extended deterrence with Japan (the Extended Deterrence Dialogue: EDD) and South Korea (the Extended Deterrence Policy Committee: EDPC).

Regarding the Japan-U.S. EDD in June 2023, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported, inter alia: Japan and the United States “reviewed conventional and U.S. nuclear capabilities contributing to regional deterrence, and highlighted the importance of optimizing the Alliance’s force posture and activities to bolster deterrence effectiveness”; “The United States reiterated its commitment to increase the visibility of U.S. strategic assets in the region”; and “Both sides also pledged to improve coordination and strengthen the Alliance’s capabilities and posture to adversary missile threats.”182

Japan also reported on the bilateral EDD held in December 2023 that “[t]he two sides shared assessments of the regional security environment, and reviewed Alliance conventional and U.S. nuclear capabilities contributing to regional deterrence and highlighted the importance of optimizing the Alliance’s force posture and activities to bolster deterrence effectiveness. The two sides discussed strategic arms control and risk reduction approaches in response to nuclear risks that are becoming increasingly challenging and complex as diversification and expansion of regional actors’ nuclear arsenals are advancing.”183

As for South Korea which has been increasing its interest in nuclear sharing with the United States, President Yoon Suk Yeol said, “The nuclear weapons belong to the United States, but planning, information sharing, exercises and training should be jointly conducted by South Korea and the United States.”184 On the other hand, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said that “We’re not discussing joint nuclear exercises.”185 Washington has also consistently denied the possibility of deploying nuclear weapons in, or jointly operating them with South Korea. However, the United States acknowledges the necessity of bolstering extended deterrence. Reflecting this stance, in February 2023, the U.S.-South Korea “Deterrence Strategy Committee Table-top Exercise” was conducted, which was based on the hypothetical scenario of North Korea using nuclear weapons.

In the Washington Declaration, adopted by the United States and South Korea at their summit in April 2023, the maintenance and strengthening of extended deterrence was stated, as follows:

The United States commits to make every effort to consult with the ROK on any possible nuclear weapons employment on the Korean Peninsula, consistent with the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review’s declaratory policy, and the Alliance will maintain robust communication infrastructure to facilitate these consultations. President Yoon reaffirmed the ROK’s longstanding commitment to its obligations under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty as the cornerstone of the global nonproliferation regime as well as to the U.S.-ROK Agreement for Cooperation Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy.

…The two Presidents announced the establishment of a new Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) to strengthen extended deterrence, discuss nuclear and strategic planning, and manage the threat to the nonproliferation regime posed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). In addition, the Alliance will work to enable joint execution and planning for ROK conventional support to U.S. nuclear operations in a contingency and improve combined exercises and training activities on the application of nuclear deterrence on the Korean Peninsula.

President Biden reaffirmed that the United States’ commitment to the ROK and the Korean people is enduring and ironclad, and that any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the ROK will be met with a swift, overwhelming and decisive response. …Going forward, the United States will further enhance the regular visibility of strategic assets to the Korean Peninsula, as evidenced by the upcoming visit of a U.S. nuclear ballistic missile submarine to the ROK, and will expand and deepen coordination between our militaries.186

The United States and South Korea agreed to convene four NCG meetings annually. Their agenda includes sharing information on nuclear weapons, conducting table-top exercises under various scenarios, and studying plans for South Korean support in U.S. nuclear operations. The inaugural meeting of the NCG was held in Seoul on July 18, and Washington and Seoul agreed to develop a concrete response plan in the event of a nuclear attack, aimed at deterring North Korea from employing nuclear weapons. They also warned: “Any nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its allies is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime.”187 Furthermore, it was also announced that the U.S. SSBN Kentucky made a port call at Busan in line with the regular visits of U.S. strategic assets mentioned in the Washington Declaration.

At the fourth Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group (EDSCG) held in Seoul in September, the United States and South Korea “reaffirmed that any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the ROK will be met with a swift, overwhelming, and decisive response. The U.S. side also reiterated that any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the United States or its allies is unacceptable and will result in the end of the Kim regime.”188

Japan-U.S.-South Korea trilateral security cooperation has also made significant progress. The first trilateral summit meeting between the leaders of these countries was held alone at Camp David in August 2023, and they issued three documents: the Camp David Principles, the Spirit of Camp David, and the Commitment to Consult Between Japan, the United States and South Korea. The “Camp David Principles” enumerates a common vision for the three countries, including: “Our countries are dedicated to honoring our commitments to non-proliferation as parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. We reaffirm that achieving a world without nuclear weapons is a common goal for the international community, and we continue to make every effort to ensure that nuclear weapons are never used again.”189 The “Spirit of Camp David” describes a wide range of efforts by the three countries to protect their common interests, including to hold multi-domain trilateral exercises on a regular basis, strengthen ballistic missile defense cooperation, establish a trilateral working group on North Korean cyber activities, expand information sharing, and counter external disinformation operations.190 They also agreed in the “Commitment to Consult among Japan, the United States and the Republic of Korea” that “[the three countries] commit [their] governments to consult trilaterally with each other, in an expeditious manner, to coordinate [their] responses to regional challenges, provocations, and threats affecting [their] collective interests and security.”191

In October 2023, the Japan Air Self-Defense Force and the U.S. and South Korean Air Forces conducted the first joint exercise in the south of the Korean Peninsula, with the participation of U.S. B-52H strategic bombers. In addition, in December, Japanese and South Korean defense officials announced the activation of a system designed for sharing real-time missile detection information between the two countries, facilitated through the United States.

Criticisms and counter-arguments

Various criticisms and objections to extended nuclear deterrence were made at the NPT PrepCom and other forums.

The NAM countries stated, “[A]ny horizontal proliferation of nuclear weapons and nuclear weapon-sharing by States Parties constitutes a clear violation of non-proliferation obligations undertaken by those [NWS] under Article I and by those [NNWS] under Article II of the Treaty. The Group therefore urges these States parties to put an end to nuclear weapon-sharing with other States under any circumstances and any kind of security arrangements in times of peace or in times of war, including in the framework of military alliances.”192 Brazil, Iran, and other countries also criticized NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangement as a violation of the NPT. South Africa stated, “The deployment of nuclear weapons in the territories of [NNWS] and the training of allied armed forces in their use is incompatible with the spirit and objectives, if not the letter, of the Treaty.”193

China has criticized U.S.-allied developments in expanded deterrence. Beijing argued, for instance:

China also calls on the relevant countries to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in national and collective security doctrines, cease the development and deployment of global missile defense system, refrain from deploying land-based intermediate range missiles in the Asia-Pacific and Europe, stop strengthening the so-called “extended deterrence”, withdraw nuclear weapons deployed overseas, give up the attempt to replicate “nuclear sharing” arrangements in the Asia Pacific, and take practical actions to reduce nuclear risks. In this regard, both nuclear-weapon States and non-nuclear-weapon States should play a positive role.194

Russia also stated the following in terms of the U.S. extended nuclear deterrence in Europe and Asia:

In the context of the overall growth of threats from the West, the retention of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, which are designed to promptly hit a wide range of targets in the Russian territory, is of major concern to us, inciting compensatory countermeasures. These weapons must be completely withdrawn to the U.S. territory and the relevant infrastructure in Europe must be dismantled.

Washington’s steps toward extending such schemes to other parts of the world, where the United States already practices so-called “extended deterrence,” also have pronounced negative implications for regional and global security. In particular, the arrangements between the United States and the Republic of Korea on joint “nuclear planning” lead to heightened tensions in the Asia-Pacific region and spur an arms race. We note with concern the official calls to expand this format to include Japan195.

In response to the above criticisms, Germany argued: “Comparisons [of Russia’s deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus] to NATO’s nuclear sharing agreements are misleading. No nuclear weapons have been stationed in countries of the former Eastern bloc. NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements have been and continue to be fully consistent with the NPT, and were put into place well before the NPT entered into force in 1970, which allowed NATO’s arrangements to be seamlessly integrated into the non-proliferation architecture. NATO Heads of State and Government have consistently stated that nuclear arrangements have always been fully consistent with the NPT, which remains the only credible path to nuclear disarmament.”196 The Baltic states have expressed criticism regarding Russia’s deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus. They argue that while the purpose of NATO’s nuclear forces is to preserve peace, prevent coercion, and deter aggression, Russia’s actions contravene its commitments under the NPT and the Budapest Memorandum of Understanding. According to the Baltic states, this deployment constitutes a provocation and poses an additional threat to global security.197 Japan exercised its right of reply and explicitly clarified that it does not intend to engage in discussions with the United States regarding nuclear sharing.

F) Risk reduction

In recent years, as nuclear disarmament efforts continue to stall and even regress, coupled with rising concerns over the increased possibility of using nuclear weapon, there has been a heightened interest in nuclear risk reduction. This approach is seen as one of the few viable and concrete measures that could be collectively agreed upon to not only advance nuclear disarmament but also address these growing concerns. NNWS encompass a broad perspective on nuclear risk reduction, which includes not only the prevention of unintended use of nuclear weapons but also the prevention of their intentional use. They propose a wide array of measures for nuclear arms control and disarmament, such as reducing nuclear arsenals and improving transparency. In contrast, NWS have predominantly focused their discussions on nuclear risk reduction with an emphasis relatively more on preventing the unintended use of nuclear weapons. The Hiroshima Report conducts an analysis and evaluation of nuclear risk reduction with a primary focus on the prevention of unintended nuclear weapon use, while taking up the arguments and proposals of both sides.

Efforts by NWS

At the NPT PrepCom in 2023, China stated that discussions on nuclear risk reduction should be conducted in accordance with the following principles: upholding the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security; maintaining strategic stability and undiminished security for all; taking precedence over crisis management; requiring joint efforts of both NWS and NNWS; and properly handling the relations between nuclear risk reduction and nuclear disarmament. China also argued that dialogue and cooperation on nuclear risk reduction should be promoted, listing the following aspects—many of which were not focused on nuclear risk reduction but were nuclear disarmament measures: no first use of nuclear weapons; de-targeting and de-alerting of nuclear weapons; reduction of the role of nuclear weapons in the collective security policies of certain countries (such as ending nuclear sharing and removing nuclear weapons deployed abroad); legal instruments on negative security assurances; prevention of nuclear war; maintenance of the nuclear nonproliferation regime including no transfer of weapons-grade fissile material or other materials to NNWS); safety and security of nuclear facilities; global strategic stability (such as halting the development and deployment of missile defense systems); security challenges posed by emerging technologies; and nuclear disarmament verification.198

Russia stated, “As a matter of principle, we believe that nuclear risk reduction should be considered in the broader context of minimizing strategic risks and on the basis of a comprehensive approach that takes into account the combination of relevant factors in their interrelationship. New steps in this area should be seamlessly integrated into the process of repairing the undermined international security architecture and minimizing the potential for conflict between nuclear-weapon States by addressing the root causes of the contradictions that arise between them through equitable dialogue.”199

U.S. National Security Advisor Sullivan noted the importance of multilateral forums on strategic risk reduction, especially dialogue among the five NWS, and stated, “The P5 provides an opportunity to manage nuclear risk and arms race pressures through a mix of dialogue, transparency, and agreements.” He also proposed risk reduction measures, such as: maintaining a “human-in-the-loop” for command, control, and employment of nuclear weapons; establishing crisis communications channels among the five NWS capitals; committing to transparency on nuclear policy, doctrine, and budgeting; and setting up guardrails for managing the interplay between non-nuclear strategic capabilities and nuclear deterrence.200

In the meantime, the five NWS have not issued a joint statement on nuclear issues, including nuclear risk reduction, since January 2022. On the other hand, the working-level experts’ meeting of the NWS was held in Cairo on June 13-14, following the NWS working group on nonproliferation issues in early February 2023, where strategic risks and risk reduction measures were discussed, although the details were not disclosed.

In addition, on November 6, China and the United States held their first arms control dialogue at the director-general/assistant secretary level since the term of the Obama administration, followed by a U.S.-China summit meeting on November 15, where the two countries agreed to resume the high-level military-to-military communication, as well as the U.S.-China Defense Policy Coordination Talks and the U.S.-China Military Maritime Consultative Agreement meetings.201

Proposals by NNWS

At the NPT PrepCom in 2023, NNWS made various proposals on nuclear risk reduction.

The Stockholm Initiative (comprising 14 countries including Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland) proposed comprehensive measures and efforts for nuclear risk reductions. Eleven TPNW-supporting countries, including Austria and Mexico, also submitted working papers on nuclear risk reduction in the broadest sense.202 Australia and the Philippines co-hosted the second ASEAN Regional Forum Nuclear Risk Reduction Workshop in Brisbane in March 2023. In addition, NAM countries emphasized the necessity and importance of nuclear risk reduction, especially in view of the humanitarian aspects of nuclear weapons.203

The NAC and NAM countries also acknowledged the need for nuclear risk reduction to a certain extent. However, they have concurrently emphasized that risk reduction efforts should not be misconstrued as justifying the possession of nuclear weapons. They have asserted that nuclear risk reduction is not a substitute for nuclear disarmament, but rather an interim measure to be pursued until elimination of nuclear weapons is achieved. In addition, Iran argued, “We view the so-called ‘risk reduction measures’ as an attempt to maintain the status quo and manage the new nuclear arms race between nuclear-weapon States.”204 South Africa further criticized as stating, “[T]he risk reduction efforts being proposed while maintaining the value of deterrence are contradictory and of no value or contribution towards nuclear disarmament.”205

143 Guy Faulconbridge and Felix Light, “Putin Ally Warns NATO of Nuclear War If Russia Is Defeated in Ukraine,” Reuters, January 19, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-ally-medvedev-warns-nuclear-war-if-russia-defeated-ukraine-2023-01-19/.

144 “If Crimea Is Attacked, ‘It Will Be Grounds for the Use of Nuclear Weapons,’ Former Russian President,” Asahi Shimbun, March 24, 2023, https://digital.asahi.com/articles/ASR3S6K7FR3SUHBI 02M.html. (in Japanese)

145 “War Can Be Ended Quickly Either Through Peace Treaty or Nuclear Weapons: Top Russian Official,” Anadolu Ajansi, July 5, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/war-can-be-ended-quickly-either-throu gh-peace-treaty-or-nuclear-weapons-top-russian-official/2937713#.

146 Josh Pennington, Alex Stambaugh and Brad Lendon, “Medvedev Says Russia Could Use Nuclear Weapon If Ukraine’s Fightback Succeeds in Latest Threat,” CNN, July 31, 2023, https://edition. cnn.com/2023/07/31/europe/medvedev-russia-nuclear-weapons-intl-hnk/index.html.

147 “Statement of the United States,” General Debate, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

148 “Statement of Japan,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

149 “Statement of Russia,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

150 “Expanded Meeting of Defence Ministry Board,” Kremlin, December 19, 2023, http://en.kremlin.ru/ events/president/news/73035.

151 “Report on 6th Enlarged Plenary Meeting of 8th WPK Central Committee,” KCNA, January 1, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202301/news01/20230101-18ee.html.

152 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Watches Fire Assault Drill,” KCNA, March 10, 2023, http:// www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news10/20230310-01ee.html.

153 “Nuclear Counterattack Simulation Drill Conducted in DPRK,” KCNA, March 20, 2023, http://www. kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news20/20230320-01ee.html.

154 National Intelligence Council, “North Korea: Scenarios for Leveraging Nuclear Weapons Through 2030,” January 2023.

155 “Statement of China,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

156 “Law on DPRK’s Policy on Nuclear Forces Promulgated.”

157 United Kingdom, Global Britain in a Competitive Age.

158 NPT/CONF.2015/10, March 12, 2015.

159 Ibid.

160 For instance, see, “Statement by Russia in Exercise of the Right of Reply,” 10th NPT RevCon, August 2, 2022.

161 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.14, June 14, 2023.

162 NPT/CONF.2020/41, November 16, 2021.

163 France stated that it “considers [the] commitment [on security assurances in its statement in April 1995] legally binding, and has so stated.” See, for instance, NPT/CONF.2015/PC.III/14, April 25, 2014.

164 A/RES/78/18, December 4, 2023.

165 “Statement by the Philippines on behalf of the ASEAN,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

166 “SEANWFZ: US Committed to Non-Proliferation Regime: Blinken,” ANTARA News, July 15, 2023, https://en.antaranews.com/news/288390/seanwfz-us-committed-to-non-proliferation-regime-blinken.

167 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.10, June 14, 2023.

168 “Statement by the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (OPANAL),” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

169 “Statement by Russia,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

170 “Statement of the United States,” Cluster 2, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 7, 2023.

171 “Putin says Russia Will Station Tactical Nukes in Belarus,” Associated Press, March 26, 2023, https:// www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14870313.

172 “Why Does Russia Want Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Belarus?” Mainichi Newspapers, March 28, 2023, https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20230328/p2g/00m/0in/016000c.

173 “Moscow, Minsk Sign Documents on Placing Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Belarus,” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, May 25, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-belarus-tactical-nuclear-weapons-agreement-signed/32427691.html.

174 “Belarus Leader Says Russian Nuclear Weapons Shipments Completed, Raising Concern in Region,” Associated Press, December 25, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/belarus-leader-says-russian-nuclear-weapons-shipments-are-completed-raising-concern-in-the-region/7412211.html.

175 Mariya Knight, Uliana Pavlova and Helen Regan, “Lukashenko Offers Nuclear Weapons to Nations Willing ‘to Join the Union State of Russia and Belarus’,” CNN, May 28, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/ 2023/05/28/europe/lukashenko-nuclear-weapons-belarus-russia-intl-hnk/index.html.

176 “Leader of Belarus Says He Wouldn’t Hesitate to Use Russian Nuclear Weapons to Repel Aggression,” Associated Press, June 13, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/russia-belarus-lukashenko-nuclear-weapons-6f97b76288f8cb9c0490c5151d588b3e.

177 “Belarus Leader Says Nuclear Arms Will Not Be Used,” Reuters, June 30, 2023, https://www.reuters. com/world/europe/belarus-leader-says-nuclear-arms-will-not-be-used-2023-06-30/.

178 NATO, Strategic Concept, June 29, 2022, p. 8.

179 Germany, National Security Strategy, 2023, p. 32.

180 Joseph Trevithick, “Poland Wants to Host NATO Nukes to Counter Russia,” The War Zone, June 30, 2023, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/poland-wants-to-host-nato-nukes-to-counter-russia.

181 Tobias Billström, “Statement of Foreign Policy 2023,” Government Offices of Sweden, February 15, 2023, https://www.government.se/speeches/2023/02/statement-of-foreign-policy-2023/.

182 “Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, June 28, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press1e_000445.html.

183 “Japan-U.S. Extended Deterrence Dialogue,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, December 7, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/pressite_000001_00032.html.

184 Soo-Hyang Choi and Trevor Hunnicutt, “Biden Says U.S. Not Discussing Nuclear Exercises with South Korea,” Reuters, January 3, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-korea-us-eye-exer cises-using-nuclear-assets-yoon-says-newspaper-2023-01-02/.

185 Olivia Olander, “White House: U.S. Coordinating with South Korea on Responses to the North, Including Nuclear Scenarios,” Politico, January 3, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/01/03/us-south-korea-north-nuclear-00076201.

186 “Washington Declaration,” White House, April 26, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/04/26/washington-declaration-2/.

187 “Joint Readout of the Inaugural U.S.-ROK Nuclear Consultative Group Meeting,” July 18, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing- room/statements-releases/2023/07/18/joint-readout-of-the-inaugural-u-s-rok-nuclear-consultative-group-meeting/.

188 U.S. Department of State, “Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group,” September 15, 2023, https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-extended-deterrence-and-consultation-group/.

189 “Camp David Principles,” Japan-U.S.-ROK Summit, August 18, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj /files/100541768.pdf.

190 “The Spirit of Camp David: Joint Statement of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States,” Japan-U.S.-ROK Summit, August 18, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100541826.pdf.

191 “Commitment to Consult among Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States,” Japan-U.S.-ROK Summit, August 18, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100541772.pdf.

192 “Statement by the NAM countries,” Cluster 2, First NPT PrepCom, August 4, 2023.

193 “Statement of South Africa,” General Debate, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

194 “Statement of China,” General Debate, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

195 “Statement of Russia,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

196 “Statement by Germany,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

197 “Statement by Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania,” General Debate, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

198 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.30, August 2, 2023.

199 “Statement of Russia,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

200 Theresa Hitchens, “White House Pushes P-5 Agreement on Missile Launch Notification, Prods China to Talk,” Breaking Defense, June 2, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/06/white- house-pushes-p-5-agreement-on-missile-launch-notification-prods-china-to-talk/.

201 “Readout of President Joe Biden’s Meeting with President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China,” November 15, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/11/15/ readout-of-president-joe-bidens-meeting-with-president-xi-jinping-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-2/.

202 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.24, July 25, 2023.

203 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.5, June 13, 2023.

204 “Statement of Iran,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

205 “Statement of South Africa,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

-150x150.jpg)