Hiroshima Report 2024(5) Reduction of Nuclear Weapons

A) Reduction of nuclear weapons

Russia and the United States had conducted the on-site inspections stipulated in the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START)—which entered into force in February 2011 and whose deadline was extended for five years in February 2021—since it entered into force. However, on-site inspections have been suspended since April 1, 2020, due at first to the global pandemic of COVID-19. Then, after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Moscow criticized Washington in August 2022 for its inability to conduct on-site inspections in the United States due to U.S. sanctions against Russia and other factors. The United States refuted the Russia’s claim, and called for dialogues to resume on-site inspections. Although both countries agreed to hold a Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC) meeting at the end of November 2022, Russia subsequently postponed it.

Ambassador Bruce Turner, the U.S. Permanent Representative to the CD, stated in January 2023, “We are … disappointed that Russia—as recently as yesterday—has refused to reschedule the session within the timeframe prescribed by the Treaty.”61 On the other hand, Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov criticized the United States, stating, “The situation does not, frankly speaking, allow for setting a new date … taking into account this escalation trend in both rhetoric and actions by the United States.”62 He also said, “The entire situation in the sphere of security, including arms control, has been held hostage by the US line of inflicting strategic defeat on Russia,”63 and “New START may well fall victim to this. We are ready for such a scenario.”64

On January 31, 2023, the U.S. Department of State reported as follows in its annual report to Congress on the implementation of New START:

Based on the information available as of December 31, 2022, the United States cannot certify the Russian Federation to be in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty. In refusing to permit the United States to conduct inspection activities on Russian territory, based on an invalid invocation of the “temporary exemption” provision, Russia has failed to comply with its obligation to facilitate U.S. inspection activities, and denied the United States its right to conduct such inspection activities. The Russian Federation has also failed to comply with the obligation to convene a session of the Bilateral Consultative Commission (BCC) within the timeline set out by the Treaty.65

The annual report also stated, “The United States also has a concern regarding Russian compliance with the New START Treaty warhead limit. This concern stems from Russia’s noncompliance with its obligation to facilitate inspection activities, coupled with its close proximity to the New START Treaty warhead limit. … [I]t is not a determination of non-compliance. … The United States also assesses that Russia was likely under the New START warhead limit at the end of 2022.” Furthermore, the United States concluded as following: “While the United States cannot certify that the Russian Federation is in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty, it does not determine … that Russia’s non-compliance specified in this report threatens the national security interests of the United States.”66

Russia responded that it “categorically reject[ed] the US representatives’ allegations about Russia’s non-compliance with the provisions of the New START Treaty,”67 and stated:

Regarding the suspension of inspection activities under the treaty, we would like to note that it was the US activities that violated the standard inspection procedures. Washington adopted anti-Russia restrictions, which prevented the Russian Federation from holding unobstructed inspections in the territory of the United States and thereby created obvious unilateral advantages for the American party.

The US’s intention to resume inspections in Russia without prior arrangement forced us to temporarily withdraw our strategic facilities from the inspection regime of the treaty, which is envisaged in its provisions. These measures do not run contrary to the New START Treaty. Their goal is to ensure the stable operation of all the treaty mechanisms in strict compliance with the principles of parity and equality of the sides, which have been put in question by the United States’ activities.

Subsequently, in his annual address to the Federal Assembly on February 21, President Putin said that while Russia had not withdrawn from New START, “[t]hey want[ed] to inflict a strategic defeat on us and also to get to our nuclear sites.” And he stated, “In this regard, I am compelled to announce today that Russia is suspending its membership in the New START Treaty.” In addition, President Putin argued: “Before we come back to discussing this issue, we must have a clear idea of what NATO countries such as France or Great Britain have at stake, and how we will account for their strategic arsenals.”68

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia stated on the same day that the decision by President Putin was the result of the “destructive actions” by the United States, and argued that “Washington [had] long been substantially violating the fundamental provisions of the Treaty on the quantitative restrictions of the parties’ relevant armaments,” including the unilateral withdrawal from the accountability by renaming its strategic weapons. At the same time, Russian Foreign Ministry stated, “[Russia] will continue to strictly comply with the quantitative restrictions stipulated in the Treaty for strategic offensive arms within the life cycle of the Treaty. Russia will also continue to exchange notifications of [intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM)] launches with the United States in accordance with the relevant Soviet-US agreement signed in 1988.” It also said, “The decision to suspend the New START Treaty can be reversed if Washington demonstrates the political will and takes honest efforts towards general de-escalation and the creation of conditions for resuming the comprehensive operation of the Treaty and, consequently, its viability.”69

The law stipulating the suspension of Russia’s implementation of the New START was approved by the Russian Federal Assembly (both the State Duma and the Federation Council) on February 22, and was signed by the President on February 28. On the same day, the Russian Foreign Ministry formally notified the United States of the suspension of the treaty’s implementation.

Russia continued to criticize the U.S. response. On March 1, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov said that Washington and Moscow had confidential discussions on matters related to the treaty, and that Russia would be open to such an exchange of views in the future. At the same time, he emphasized that “[u]ntil the United States changes its behavior, until we see signs of common sense in what they are doing in relation to Ukraine … we see no chance for the decision to suspend New START to be reviewed or re-examined.”70 In his statement at the CD on March 2, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov once again justified his country’s actions, stating: “The situation has further degraded following the US attempts to ‘probe’ the security of the Russian strategic facilities declared under the New START Treaty by assisting the Kiev regime in conducting armed attacks against them. Against this background, we perceived as highly cynical those demands by Washington to regain access to Russia’s nuclear facilities for inspecting them under the Treaty. … Under these circumstances, we were forced to announce the suspension of the Treaty.”71

Russia suspended to provide data on its strategic nuclear forces to the United States as part of its suspension of implementation of New START. In response, the United States announced on March 28 that it would also no longer provide data on its strategic nuclear weapons as a countermeasure. John Plumb, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, said that “Russia responded that they [would] not be providing that information” while the United States had pressed Russia about the exchange of information, due at the end of March.72 Principal Deputy Spokesperson Vedant Patel also said, “the suspension [by Russia] was legally invalid. Russia’s failure to exchange this data will therefore be a violation of the treaty, adding on to its existing violations of the New START Treaty and, as a result, lawful countermeasures intended to encourage Russia to return to compliance with the treaty. And the U.S. will likewise not provide its biannual data update to Russia.”73

On March 29, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov announced that Russia would suspend advance notification of missile launch tests under New START as a countermeasure to the U.S. refusal to provide data.74 On April 4, he also stated that the suspension of New START implementation would prevent the United States from conducting inspections and sharing data, thereby hindering U.S. intelligence gathering, which had been employing “any channel, any window to see into our military world.”75 At the same time, Russia stated that the advanced notification of missile tests to the United States under the Ballistic Missile Launch Notification Agreement signed in 1988 would be continued.76 In fact, both countries gave advance notice to the other concerning ICBM launch tests that each conducted in 2023.

On June 1, the United States adopted the following measures as the “additional lawful countermeasures for the purpose of encouraging the Russian Federation to return to compliance with the treaty”:77

➢ The United States began to withhold from the Russia all the notifications required under paragraph 2 of Article VII of the New START. The United States will continue to provide notification of ICBM and SLBM launches in accordance with the 1988 Ballistic Missile Launch Notification Agreement and to provide notifications of exercises in accordance with the 1989 Agreement on Reciprocal Advance Notification of Major Strategic Exercises.

➢ The United States is refraining from facilitating Russian New START Treaty inspection activities on U.S. territory, specifically by revoking existing visas issued to Russian New START Treaty inspectors and aircrew members, denying pending applications for such visas, and by revoking the standing diplomatic clearance number issued for Russian inspection airplanes.

➢ The United States will not provide telemetric information on launches of U.S. ICBMs and SLBMs.

Meanwhile, both Washington and Moscow have expressed their intention to continue to comply with the treaty’s obligations regarding the quantitative limits on their strategic nuclear arsenals.

In this regard, the United States stated on July 1, “[It] assesses that, as of July 1, 2023, the Russian Federation has not engaged in significant activity above the New START Treaty central limits. U.S. confidence in the Russian Federation’s adherence to the treaty’s central limits will diminish over time if the Russian Federation persists in not implementing the treaty’s verification provisions.”78

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan stated on June 2 that the United States was prepared to discuss without preconditions how the United States and Russia could manage nuclear risks and how a new nuclear arms control framework could be established.79 However, there were neither U.S.-Russian talks on re-implementation of the New START during 2023, nor concrete proposals from them for its re-implementation or for future bilateral nuclear arms control.

In the meantime, many countries urged Russia to re-implement New START at the NPT PrepCom in 2023. However, Russia justified its actions on the New START by stating:

The destructive actions of the United States continued to have a devastating effect on the arms control architecture, which it had already largely destroyed. This led, in particular, to the suspension of the New START Treaty. Russia’s forced decision was a justified, legitimate and practically inevitable reaction to Washington’s undermining of the fundamental principles and understandings on which the New START Treaty was based and to the following fundamental change of circumstances. The American side’s failure to observe the central quantitative limits under the New START Treaty and its assistance to the Kiev regime in attacking our strategic facilities subject to the Treaty also dealt a severe blow to its viability.

Given the “freezing” of the New START Treaty and the earlier collapse of the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty)] caused by the United States, Russia is taking a number of measures to maintain predictability and stability in the nuclear missile sphere. We continue to adhere to the central quantitative limits stipulated in the New START Treaty, inform the United States of launches of ICBMs and SLBMs through an exchange of relevant notifications, and observe a unilateral moratorium on the deployment of ground launched intermediate- and shorter-range missiles until similar U.S.-made weapons emerge in relevant regions. At the same time, this moratorium is under serious pressure in view of the Pentagon’s active preparations for the deployment of ground-launched intermediate- and shorter-range missiles in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region.80

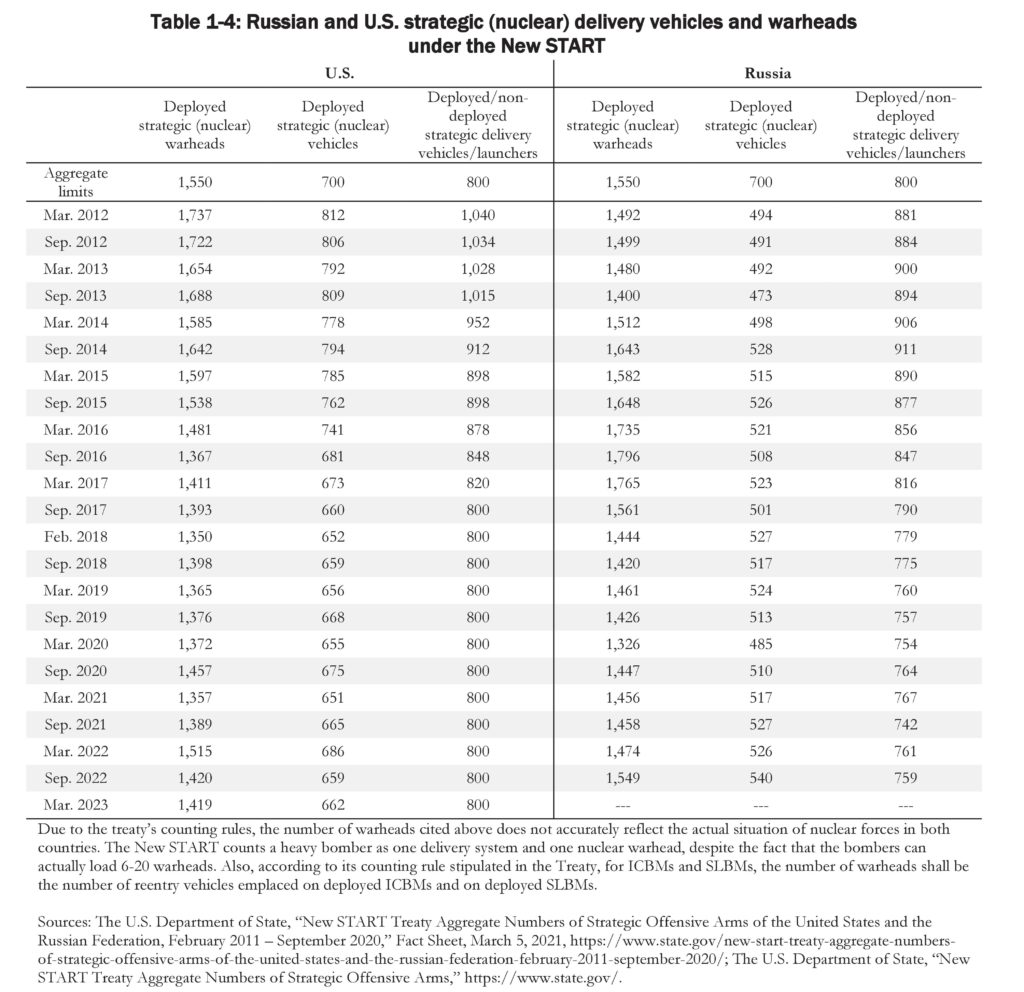

While the status of their strategic (nuclear) delivery vehicles and warheads under New START had been periodically updated on the U.S. Department of State homepage, as a result of Russia’s suspension of implementation, the data as of March 2023 only includes the number of U.S. strategic forces. In addition, even the data for the United States as of September 2023 has not been published (see Table 1-4).81 According to the data as of February 5, 2018—the deadline for reducing their strategic arsenals under the treaty—the number of Russian and U.S. deployed strategic delivery vehicles and deployed/non-deployed strategic delivery vehicles/launchers, besides deployed strategic warheads, fell below the limit.

B) A concrete plan for further reduction of nuclear weapons

In 2023, there was no new proposal by nuclear-armed states to take concrete measures for further reductions of their nuclear arsenals.

In his speech in June 2023, U.S. National Security Advisor Sullivan expressed that “we have stated our willingness to engage in bilateral arms control discussions with Russia and with China without preconditions.” He also said, “[R]ather than waiting to resolve all of our bilateral differences—the United States is ready to engage Russia now to manage nuclear risks and develop a post-2026 arms control framework.” Regarding China, he argued that Beijing “has thus far opted not to come to the table for substantive dialogue on arms control.”82 The United States also called for arms control dialogues with Russia and China at the NPT PrepCom, stating: “It is time for Russia to return to compliance with New START and engage with us to manage nuclear risks and discuss a post-2026 nuclear arms control framework. It is time for the PRC substantively to engage with us on strategic nuclear issues in order to avoid risks of miscalculation and miscommunication.”83

On the other hand, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov said, “I would like to say that on the basis that the Americans are now proposing, we are not ready to conduct this dialogue and will not be, because they ignore several key points in the entire configuration. Namely, we must, first of all, make sure that the US course, which is fundamentally hostile towards Russia, is changing for the better for us. This is not happening, not even close.”84 In October, he said that Moscow had received an informal memo from the United States calling for renewed dialogue. He added, “[Washington] suggests putting dialogue on strategic stability and arms control on a systematic footing, doing so in isolation from everything that is going on. … We are not ready for this. It is simply impossible to return to dialogue on strategic stability, including New START… without changes in the United States’ deeply, fundamentally hostile course towards Russia.”85

China has consistently insisted that any participation on its part in the nuclear weapons reduction process would be premature. At the NPT PrepCom in 2023, China stated, “The priority now is that the countries with the largest nuclear arsenals should fulfil their special and primary responsibilities for nuclear disarmament, continue to effectively implement the New START Treaty and further reduce their nuclear arsenals in a significant and substantive manner, so as to create the conditions for other nuclear-weapon States to join the nuclear disarmament process.”86 China also argued: “Requiring countries with vast difference in nuclear policies and numbers of nuclear weapons to undertake the same nuclear disarmament obligations is against the historical and realistic logic, and will surely lead the international nuclear disarmament process to a dead end.”87

In November, China and the United States held their first arms control dialogue at the director-general/assistant secretary level since the Barack Obama administration. According to the U.S.

Department of State, “The two sides held a candid and in-depth discussion on issues related to arms control and nonproliferation as part of ongoing efforts to maintain open lines of communication and responsibly manage the U.S.-PRC relationship.” It also reported that “[t]he United States emphasized the importance of increased PRC nuclear transparency and substantive engagement on practical measures to manage and reduce strategic risks across multiple domains, including nuclear and outer space.”88 However, no substantive progress was made, and there was reportedly no agreement on holding the next round of talks.89

C) Trends on strengthening/ modernizing nuclear weapons capabilities

While nuclear-armed states have reiterated their commitments to promoting nuclear disarmament, they continue to modernize and/or strengthen their nuclear weapons capabilities. At the NPT PrepCom, many NNWS expressed strong concerns about the trend toward modernization of nuclear forces. For instance, the NAM countries stated, “The Group of Non-Aligned States Parties to the Treaty reiterates with concern that improvements in existing nuclear weapons and the development of new types of nuclear weapons as provided for in the military doctrines of some nuclear-weapon States, including the United States Nuclear Posture Review, violate their legal obligations on nuclear disarmament, as well as the commitments made to diminish the role of nuclear weapons in their military and security policies, and contravene the negative security assurances provided by the nuclear-weapon States.”90

According to a report published by the ICAN in June 2023, the total amount of nuclear weapons-related expenditures (including modernization of nuclear forces) by nine nuclear-armed states in 2022 was estimated at $82.9 billion, of which $43.7 billion was spent by the United States, approximately $11.7 billion by China, $9.6 billion by Russia, $6.8 billion by the United Kingdom, and $5.6 billion by France.91

China

China has reiterated that “[it] always keeps its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security, and does not seek parity with other countries in terms of its nuclear-weapons investment, quantity or scale. China never participates in arms race in any form.”92 However, Beijing has not disclosed any information regarding development and deployment of its nuclear arsenals. Consequently, the actual status of these arsenals remains unclear.

In recent years, there is growing concern that China’s nuclear weapons modernization has accelerated. According to the annual report on Chinese military and security developments published in November 2023, the U.S. Department of Defense estimated as following: “[China] will probably have over 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030, much of which will be deployed at higher readiness levels and will continue growing its force to 2035 in line with its goal of ensuring [People’s Liberation Army (PLA)] modernization is “basically complete” that year, which serves as an important milestone on the road to [Xi Jinping’s] goal of a “world class” military by 2049.93 In February 2023, a senior U.S. military official reportedly informed Congress that as of the October 2022, China had more ground-based fixed and mobile ICBM launchers than the number of U.S. ICBM launchers.94

The main component of China’s strategic nuclear forces is ICBMs. For a long time, China’s only strategic nuclear forces capable of reaching the U.S. homeland were the 20 DF-5 silo-based ICBMs which began to be deployed in 1981. However, since the latter half of the 2000s, it has introduced DF-31A/AG mobile ICBMs, DF-5B silo-based ICBMs with MIRVs that can carry three to five warheads per a missile, and DF-41 MIRVed ICBMs which can mount up to 10 warheads per a missile (while it is also considered to carry about three warheads as well as some decoys). The U.S. Department of Defense assesses that “[t]he PRC probably completed the construction of its three new solid-propellant silo fields in 2022, which consists of at least 300 new ICBM silos, and has loaded at least some ICBMs into these silos,”95 and estimates that China has respectively 350 ICBM launchers and 500 ICBMs in its arsenal.96

China is also strengthening its SLBM capabilities. The U.S. Defense Department assesses that China is conducting continuous at-sea deterrence patrols with its six JIN-class (Type 094) SSBNs, which are equipped to carry JL-2 or JL-3 SLBMs.97 The JL-3 is China’s latest SLBM with a range estimated at over 10,000 km and is capable of striking the U.S. mainland from the Chinese coast.

Meanwhile, China is completing its strategic nuclear triad with the H-6N strategic bomber which can carry nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missiles (ALBM), and the H-6K strategic bomber which can carry nuclear-capable cruise missiles.

Regarding non-strategic nuclear forces, China is estimated to maintain a high level of ground-launched short- and intermediate-range missile forces, both qualitatively and numerically. The U.S. Defense Department’s annual report on China’s military forces estimates that China has 250 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) launchers and 500 missiles, 300 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) launchers and more than 1,000 missiles, 200 short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) launchers and more than 1,000 missiles.98

In addition to ballistic and cruise missiles, China has been actively developing hypersonic missiles. It started to deploy DF-17 hypersonic missiles in 2020. It was also reported in 2023 that China had begun secretly operating the DF-27 hypersonic missile (range 5,000-8,000 km) from 2019 and conducted flight tests.99 Furthermore, it was reported in October 2021 that China conducted a test of the Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS).100

China criticized the above analysis and estimates by the U.S. Department of Defense, stating: “This U.S. report, like previous ones, is nonfactual and biased. It calls China a threat only to find a convenient pretext for the US to sustain its military hegemony. China is strongly opposed to this.”101

France

In 2015, France announced that it possessed not more than 300 nuclear weapons, and its nuclear deterrent consists of 54 middle-range ALCMs and three sets of 16 SLBMs.102 In 2022, there was no change in this nuclear force posture.

France plans to complete development of the M51.3 SLBMs by 2025, which incorporate a new third stage for extended range and further improved accuracy. The first M51.3 launch test was conducted in November 2023.103 In addition, France launched a program in 2021 to develop a third-generation SSBN (SNLE 3G) to be in service by 2035, and an M51.4 SLBM to be mounted on it by the early 2040s.104 As for the successor to the air-to-surface medium-range cruise missile (ASMPT), France has begun design and development of the ASN4G (air-sol nucléaire 4ème génération), which is scheduled to enter into service around 2035. France is also developing a hypersonic glide glider which is designed to carry a nuclear or conventional warhead. The first test of the prototype was conducted in June 2023.105

Russia

Russia has been actively promoting the development and deployment of various types of delivery vehicles, including the replacement of nuclear forces built during the Cold War era, mainly aiming to maintain nuclear deterrence against the United States.

Regarding Russia’s strategic nuclear forces, in September 2023, it was reported that the RS-28 (Sarmat) ICBM, which is expected to be the core of Russia’s future strategic nuclear capability, had been deployed.106 In December, it was also reported that the RS-28 would be deployed to a unit in southwestern Uzhul in the Krasnoyarsk region of Eastern Siberia.107 Meanwhile, Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces announced that Russia was set to complete the replacement of the older Topol-M missiles with the RS-24.108

As for its sea-based nuclear forces, the conversion to Borei-class SSBNs has begun, with three ships in service, and five more under construction.

Russia has also been active in developing “exotic” nuclear delivery systems, and there were various developments in 2023 as in the previous years. In January, it was reported that the first set of nuclear-propelled, long-range Status-6 (Poseidon) nuclear torpedoes had been produced.109 The Status-6, with a range of over 10,000 km, will be installed on the new nuclear submarine Belgorod. In March, as a base for two nuclear submarines carrying Status-6s, Russia also reportedly planned to complete construction of infrastructure facilities along its Pacific coast in early 2024.110 Further deployment of the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, which began in 2021, was also underway. In November 2023, Russian rocket forces reportedly loaded an ICBM equipped with the Avangard into a launch silo in southern Russia.111

In October, President Putin said that Russia had “conducted the last successful test of the Burevestnik nuclear- powered global-range cruise missile,”112 or the SSC-X-9 (Skyfall). This is considered to be their first successful attempt while Russia is believed to have conducted more than 10 launch tests previously, all of which ended in failure.

The United Kingdom

As mentioned above, in 2021 the United Kingdom declared in its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy that it would move to an overall nuclear warheads stockpile ceiling from not more than 180 of no more than 260 warheads.113 In addition, the United Kingdom in its national report submitted to the NPT RevCon stated, “This is a ceiling, not a target, and it is not our current stockpile number. This is fully consistent with the longstanding minimum credible deterrence posture of the United Kingdom and we will continue to keep this under review in light of the international security environment.”114In October 2017, the United Kingdom started to construct a new Dreadnought-class of four SSBNs to replace the existing Vanguard-class SSBNs. The first new SSBN is expected to enter into service in the early 2030s, but construction has been delayed due to technical problems. The SLBMs to be mounted on the new SSBNs are planned to be equipped with the W93 nuclear warhead, which is under consideration in cooperation with the United States.

The United States

The United States maintains the following modernization plans of its strategic nuclear forces:

➢ Constructing 12 Colombia-class SSBNs, the first of which commence operation in 2031;

➢ Building 400 Sentinel Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD, the new ICBMs) for replacing 450 Minuteman III; and

➢ Developing and deploying B-21 next generation strategic bombers as well as the Long Range Stand-Off Weapon (LRSO).

The United States reported that development of the LRSO was progressing well toward a production decision in 2027,115 with nine successful test flights in 2022.116 In November, the first test flight of a B-21 was also conducted. On the other hand, it is reported that development of the Sentinel ICBM could be delayed two years from its initial deployment goal of May 2029 due to supply chain issues and an absence of skilled engineers.117

Regarding nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missiles (SLCM-N), for which the Biden administration decided to discontinue development, some members of Congress and senior military officials remain to seek the maintenance of the development budget as in the previous year. In December 2023, the U.S. Congress authorized a budget of $260 million for SLCM-N for fiscal year 2024, and President Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Meanwhile, the U.S. Defense Department announced that it would pursue to develop the B61-13, a successor to the B61-7 nuclear gravity bomb. The B61-13 will have a yield similar to the B61-7, which is higher than that of the B61-12.118

The United States in its national report submitted to the NPT RevCon in 2022 reaffirmed the followings:119

➢ A decision has been taken, in conjunction with NATO, not to deploy land-based nuclear-armed missiles within Europe;

➢ The current U.S. nuclear modernization plan will not increase the number of ICBMs.

➢ The United States has no program to develop nuclear-armed nuclear-powered cruise missiles or torpedoes;

➢ The United States has no program or intent to deploy nuclear warheads on hypersonic glide vehicles or hypersonic cruise missiles.

India

India appears to be pursuing the possession of a strategic nuclear triad. In 2023, India was reportedly developing an Agni-6 ICBM (with a range of 10,000 km).120 India is also considered to be developing a MIRV, although the status of development remains unknown. Concurrently, India is progressing with the construction of its fourth SSBN, which is slated for launch. Moreover, India conducted test launches of the Pritvi-2 SRBM121 and the Agni Prime MRBM122 in 2023.

Israel

Israel123 has neither confirmed nor denied possessing nuclear weapons, and its nuclear activities are opaque. In terms of nuclear delivery means, Israel has developed and deployed both nuclear capable IRBMs and SLCMs. In January 2020, it reportedly conducted a test launch of its Jericho long-range ballistic missile.124 It is also considered that Israel is upgrading from the two-stage Jericho II IRBM to the three-stage Jericho III with a range of over 4,000 km.

Pakistan

Pakistan has prioritized the development and deployment of nuclear-capable short-, medium- and intermediate-range missiles for ensuring deterrence against India. In October 2023, Pakistan conducted test launches of the Ababeel MIRVed IRBM and the single-warhead Hatf-5 IRBM. It is also developing the Hatf-7 ground launched cruise missile (GLCM), which is designed to be capable of carrying a nuclear warhead.

North Korea

North Korea continued its active nuclear and missile development in 2023.125

During the military parade on February 8, 2023, commemorating the 75th anniversary of the North Korean People’s Army, there was a prominent display of 12 mobile launchers for the Hwasong-17 ICBM, alongside 24 launchers for SRBM and land-attack cruise missile (LACM) launchers designated as “tactical nuclear weapons operation units.”126 The Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) reported that the ICBMs “demonstrat[ed] the signal development of the military capability and tremendous nuclear strike capability” of North Korea, and that its “tactical nuclear weapons operation units entered the … powerful war deterrent and counterstrike ability.”127

On February 18, North Korea conducted a launch drill of a Hwasong-15 ICBM. According to the KCNA, the missile was launched on a lofted trajectory, with a maximum altitude of 5,768.5 km and a range of 989 km for 4,015 seconds before hitting the pre-set area in open waters of the Sea of Japan. It also reported that “[t]he drill was suddenly organized without previous notice,” and that “through a sudden launching drill, the reliability of the weapon system should be re-confirmed and verified while getting the combat preparedness of the DPRK nuclear force recognized and proving confidence and guarantee for correct operation, reactivity, reliability, effectiveness and combat capability of the components of the state nuclear deterrence.”128

On March 16, it conducted a launch drill of a Hwasong-17 ICBM, flying 1,000.2 km in 4,151 seconds at a maximum altitude of 6,045 km. The KCNA reported that “[t]he drill confirmed the war readiness of the ICBM unit,” and that Chairman Kim Jong Un “stressed the need to strike fear into the enemies, really deter war and reliably guarantee the peaceful life of our people and their struggle for socialist construction by irreversibly bolstering up the nuclear war deterrent.”129 Another commentary said, “They can be used anytime, if necessary, to discharge the sacred mission of defending the country, and they should be preemptively used anytime according to the strategic plan, if a conflict with possibility of dangerous escalation occurs. The recent ICBM Hwasongpho-17 launching drill is clear evidence of it.”130

On April 13 and July 13, North Korea conducted launch tests of a new type of solid-fuel ICBM, the Hwasong-18. The KCNA reported that the latter test was a “new record” with a maximum altitude of 6,648.4 km and a flight time of 4,491 seconds.131 Furthermore, North Korea also conducted a “launch drill” (not a test launch) for the Hwasong-18 on December 18. According to the KCNA, “[t]he missile traveled up to a maximum altitude of 6,518.2 km and flew a distance of 1,002.3 km for 4,415s before accurately landing on the preset area in the open waters off” the Sea of Japan.132

North Korea has also consistently demonstrated a persistent commitment to the development and enhancement of its non-strategic nuclear forces. On February 20, “relevant multiple launch rocket firepower sub-units of the KPA long-range artillery unit on the western front set virtual targets 395 km and 337 km away from the launching points respectively and fired two shells of 600 mm multiple rocket launchers.” The KCNA reported that the multiple rocket launchers were a “tactical nuclear attack means,” which “can reduce to ashes the enemy’s operational airfield to paralyze its function, and that North Korea “fully demonstrated its full readiness to deter and will to counter the U.S. and south Korean combined air force bragging about their air superiority.”133 The U.S. Forces’ Gunsan Air Base is situated roughly 390 km away from the designated launch sites. Additionally, the South Korean Air Force’s Cheongju Air Base is located approximately 340 kilometers from the launch site.

North Korea conducted a launch drill of four Fasal-2 strategic cruise missiles on February 23, and reported that it flew 2,000 km for 2 hours and 50 minutes in an elliptical and eight-shaped flight orbits, and hit the target.134 During the “Nuclear Counterattack Simulation Drill” on March 18-19, it was reported that “[t]he tactical ballistic missile launched in Cholsan County, North Phyongan Province accurately exploded at 800 meters above the target waters in the East Sea of Korea set in its 800 km strike range, thus proving once again the reliability of the operation of nuclear explosion control devices and detonators fitted in the nuclear warhead.”135 In November, North Korea also announced that it had successfully conducted tests on solid-fuel engines for IRBMs.136

North Korea’s launch tests and drills, using submarines as platforms for deploying nuclear forces, garnered attention. On March 12, it executed an underwater launch drill using a submarine to deploy two strategic cruise missiles. According to the state media, these missiles precisely hit the preset target on the Sea of Japan after traveling the 1,500km-long eight-shaped flight orbits for 7,563 to 7,575 seconds.137 This event is regarded as the first instance of a cruise missile launch drill being executed from a submarine.

On March 24, Pyongyang conducted a test launch of “Unmanned Underwater Nuclear Attack Craft ‘Haeil,’” and detonated a test warhead after more than 59 hours of cruising. The KCNA reported that “[t]he mission of the underwater nuclear strategic weapon is to stealthily infiltrate into operational waters and make a super-scale radioactive tsunami through underwater explosion to destroy naval striker groups and major operational ports of the enemy.”138 In early April, it also launched the Haeil-2, which North Korea positioned as a “underwater strategic system.” It cruised “1,000 km of simulated underwater distance in elliptical and ‘8’ patterns set … for 71 hours and 6 minutes,” and “the test warhead accurately detonated underwater.”139

On September 8, the “Hero Kim Kun Ok,” a tactical nuclear attack submarine capable of carrying SLBMs, was unveiled. Chairman Kim Jong Un stated at a ceremony for launching newly-built submarine on September 6, “[T]his submarine constitutes a menacing means as it is capable of carrying a large number of means for delivering nukes of various powers and of launching a preemptive or retaliatory strike at the hostile states in any waters.”140 It is estimated that this submarine is equipped with 10 vertical launch tubes for missiles, and that four large hatches would be for the Puksuksong SLBMs and the six smaller missile hatches may be used for the modified KN-23 SLBM.141

During the year, North Korea conducted multiple launches of the “Chollima-1” rocket, which carried a reconnaissance satellite. The attempts in May and August resulted in failure. However, following the Russo-North Korean summit, North Korea proclaimed the November launch of the Chollima-1 as a success. It also announced that the reconnaissance satellite “Malligyong-1” had been successfully placed into space orbit.142

61 “U.S. Statement at the 2023 Session of the Conference on Disarmament Delivered by Ambassador Bruce Turner,” January 24, 2023, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2023/01/24/u-s-statement-at-the-2023-sessi on-of-the-conference-on-disarmament/.

62 “No Date Set for Talks with US on Nuclear Arms Treaty, Moscow Says,” Alarabiaya News, January 23, 2023, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/world/2023/01/23/Moscow-sees-no-prospects-for-US-Russi an-meeting-on-New-START-treaty-Agencies.

63 Matthew Gault, “The Last Existing U.S.-Russia Nuclear Treaty Could Soon Fail,” Vice, January 31, 2023, https://www.vice.com/en/article/5d3xkz/the-last-existing-us-russia-nuclear-treaty-could-soon-fail.

64 “Nuclear Arms Control Treaty with US Could Be in Danger, Russia Warns,” Press TV, January 30, 2023, https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2023/01/30/697290/Russia-US-nuclear-arms-New-START.

65 U.S. Department of State, “Report to Congress on Implementation of the New START Treaty,” January 31, 2023, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-New-START-Implementation-Report.pdf.

66 Ibid.

67 Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Foreign Ministry statement regarding the Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START),” February 8, 2023, https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1852877/?lang=en.

68 “Presidential Address to Federal Assembly,” February 21, 2023, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/ news/70565.

69 “Foreign Ministry Statement in Connection with the Russian Federation Suspending the Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, February 21, 2023, https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1855184/.

70 “Russia Will Not Rejoin Nuclear Treaty Unless U.S. Changes Ukraine Stance – Deputy Foreign Minister,” Reuters, March 1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-will-not-rejoin-nuclear-treaty-unless-us-changes-ukraine-stance-deputy-2023-03-01/.

71 “Statement by Russia,” CD, March 2, 2023, https://docs-library.unoda.org/Conference_on_Disarma ment_-_(2023)/russian_federation_English.pdf.

72 Darya Tarasova and Tim Lister, “Russia Says It Has Suspended All Nuclear Notifications With US, According to State Media,” CNN, March 29, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/europe/live-news/russia-ukraine-war-news-03-29-23/h_2b78bd8f12b5b50d4a41612998336ecf.

73 “Department Press Briefing,” U.S. Department of State, March 28, 2023, https://www.state.gov/ briefings/department-press-briefing-march-28-2023/.

74 “Russia Suspends Advance Notice of Missile Tests, including ICBMs,” Nikkei, March 29, 2023, https:// www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOGN290BR0Z20C23A3000000/. (in Japanese)

75 “Moscow Suspends New START to Thwart US Intel Collection,” Press TV, April 6, 2023, https:// www.presstv.ir/Detail/2023/04/04/700973/Russia-US-New-START-Ryabkov-Ukraine-Putin-Biden-nuclear-weapons.

76 Vladimir Isachenkov, “Russia to Keep Missile Test Notices under Cold War-Era Deal,” AP, March 31, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/russia-us-nuclear-start-treaty-test-warnings-5e7efae0ab2d52ece5d5e1e 8609152b0.

77 “Report on the Reasons That Continued Implementation of the New START Treaty Is in the National Security Interest of the United States,” U.S. Department of State, July 6, 2023, https://www.state.gov/ report-on-the-reasons-that-continued-implementation-of-the-new-start-treaty-is-in-the-national-security-interest-of-the-united-states/.

78 Ibid.

79 “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan for the Arms Control Association (ACA) Annual Forum”, The White House, June 2, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/06/02/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-for-the-arms-control-association-aca-annual-forum/.

80 “Statement of Russia,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

81 The United States also had declassified the number of each type of its strategic delivery vehicles through September 2020. However, it has not done so since then.

82 “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan for the Arms Control Association (ACA) Annual Forum.”

83 “Statement of the United States,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

84 Mohammad Ali, “Russia Did Not Receive US Proposals on Arms Control – Foreign Ministry,” Urdupoint, July 21, 2023, https://www.urdupoint.com/en/world/russia-did-not-receive-us-proposals-on-arms-c-17 27105.html.

85 “Russia Says U.S. Must End ‘Hostility’ for Nuclear Talks,” The Moscow Times, October 25, 2023, https:// www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/10/25/russia-says-us-must-end-hostility-for-nuclear-talks-a82882.

86 “Statement of China,” General Debate, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

87 “Statement of China,” Cluster 1, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 3, 2023.

88 “Assistant Secretary Mallory Stewart’s Meeting with the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director-General of Arms Control Sun Xiaobo,” U.S. Department of State, November 7, 2023, https://www.state.gov/assistant-secretary-mallory-stewarts-meeting-with-the-peoples-republic-of-chinas-prc-ministry-of-foreign-affairs-director-general-of-arms-control-sun-xiaobo/.

89 Jonathan Landay and Arshad Mohammed, “US Says China Reveals Little in Arms Control Talks,” U.S. News, November 7, 2023, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-11-07/us-chinese-offi cials-held-arms-control-talks-on-monday-state-dept.

90 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.8, June 14, 2023.

91 ICAN, Wasted: 2022 Global Nuclear Weapons Spending, June 2023, https://www.icanw.org/wasted_ 2022_global_nuclear_weapons_spending.

92 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.28, November 29, 2021.

93 The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, October 2023, p. viii.

94 “China’s ICBM Launches Surpass United States, U.S. Military Officials Inform Congress,” CNN, February 8, 2023, https://www.cnn.co.jp/usa/35199740.html. (in Japanese)

95 The U.S. DOD, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023, p. viii.

96 Ibid., p. 67.

97 Ibid., p. 108.

98 Ibid., p. 67.

99 “Leaked Classified Documents, Information on China: Hypersonic Glide Weapons ‘Break Through U.S. System with High Probability,’” Yomiuri Shimbun, April 12, 2023, https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/world/ 20230412-OYT1T50170/. (in Japanese)

100 “A Fractional Orbital Bombardment System with a Hypersonic Glide Vehicle?” Arms Control Wonk, October 18, 2021, https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1213655/a-fractional-orbital-bombard ment-system-with-a-hypersonic-glide-vehicle/.

101 “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning’s Regular Press Conference,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, October 20, 2023, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/202310/t2023 1020_11165059.html.

102 François Hollande, “Nuclear Deterrence—Visit to the Strategic Air Forces,” February 19, 2015, http:// basedoc.diplomatie.gouv.fr/vues/Kiosque/FranceDiplomatie/kiosque.php?fichier=baen2015-02-23. html#Chapitre1.

103 “France Says Successfully Tests Ballistic Missile,” Barron’s, November 18, 2023, https://www.barrons. com/news/france-says-successfully-tests-ballistic-missile-6cee866d.

104 “France Launches Program to Build New Generation of Nuclear Submarines,” Marine Link, February 19, 2021, https://www.marinelink.com/news/france-launches-program-build-new-485431; Timothy Wright and Hugo Decis, “Counting the Cost of Deterrence: France’s Nuclear Recapitalization,” Military Balance Blog, May 14, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/05/france-nuclear-recapita lisation.

105 “France Conducts Maiden Test of Hypersonic Glider,” Reuters, June 28, 2023, https://www.reuters. com/business/aerospace-defense/france-conducts-maiden-test-hypersonic-glider-2023-06-27/.

106 “Russia Deploys Sarmat ICBM for Combat Duty,” The Moscow Times, September 1, 2023, https:// www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/09/01/russia-deploys-sarmat-icbm-for-combat-duty-a82333.

107 “Russian ICBMs Deployed in Eastern Siberia, Latest Heavyweight ‘Sarmat,’” Kyodo News, December 16, 2023, https://www.47news.jp/10273993.html.

108 Michael Starr, “Russia to Modernize Nuclear Forces in 2023, Add More Multi-Warhead Nukes,” Jerusalem Post, January 3, 2023, https://www.jpost.com/international/article-726527.

109 Guy Faulconbridge, “Russia Produces First Set of Poseidon Super Torpedoes – TASS,” Reuters, January 17, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-produces-first-nuclear-warheads-poseidon-super-torpedo-tass-2023-01-16/.

110 “Russia to Complete Infrastructure for ‘Poseidon’ Equipped Submarines in 2024,” Reuters, March 27, 2023, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-10-05/russia-has-tested-a-nuclear-powered-missile-and-could-revoke-a-global-atomic-test-ban-putin-says. (in Japanese)

111 “Russia Loads Missile with Nuclear-Capable Glide Vehicle into Launch Silo,” Reuters, November 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-installs-one-more-hypersonic-nuclear-missile-ifax-2023-11-16/.

112 “Russia Has Tested a Nuclear-Powered Missile and Could Revoke a Global Atomic Test Ban, Putin Says,” U.S. News & World Report, October 5, 2023, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-10-05/russia-has-tested-a-nuclear-powered-missile-and-could-revoke-a-global-atomic-test-ban-putin-says.

113 United Kingdom, Global Britain in a Competitive Age, p. 76.

114 NPT/CONF.2020/33, November 5, 2021.

115 John A. Tirpak, “LRSO Stealth Nuclear Missile on Track for Production Decision in 2027,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, April 25, 2023, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/lrso-production-decision-2027/.

116 John A. Tirpak, “New Details of Secret LRSO Missile: Nine Successful Flight Tests in 2022,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, October 2, 2023, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/secret-lrso- missile-nine-successful-flight-tests-2022/.

117 Shannon Bugos and Gabriela Iveliz Rosa Hernández, “New U.S. ICBMs May Be Delayed Two Years,” Arms Control Association, May 2023, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2023-05/news/new-us-icbms-may-delayed-two-years.

118 “Department of Defense Announces Pursuit of B61 Gravity Bomb Variant,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 27, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3571660/depart ment-of-defense-announces-pursuit-of-b61-gravity-bomb-variant/.

119 NPT/CONF.2020/47, December 27, 2021.

120 Vaibhav Agrawal, “Rocketing to Uncertainty: Agni 6 ICBM – India’s Bold Aspiration or Reckless Ambition?” Frontier India, September 26, 2023, https://frontierindia.com/rocketing-to-uncertainty-agni-6-icbm-indias-bold-aspiration-or-reckless-ambition/.

121 “India Successfully Test-Fires Short-Range Ballistic Missile Prithvi-II,” PGurus, January 11, 2023, https://www.pgurus.com/india-successfully-test-fires-short-range-ballistic-missile-prithvi-ii/.

122 “India Successfully Flight-Tests New-Generation Ballistic Missile ‘Agni Prime,’” Telegraph, June 8, 2023, https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/india-successfully-flight-tests-new-generation-ballistic-missile-agni-prime/cid/1943354.

123 See, for instance, Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Nuclear Notebook: Israeli Nuclear Weapons, 2022,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 17, 2022, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2022-01/nuclear-notebook-israeli-nuclear-weapons-2022/.

124 Don Jacobson, “Israel Conducts Second Missile Test in 2 Months,” UPI, January 31, 2020, https:// www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2020/01/31/Israel-conducts-second-missile-test-in-2-months/ 3481580486615/.

125 See also “North Korean Missile Launches & Nuclear Tests: 1984-Present,” CSIS Missile Threat Project, https://missilethreat.csis.org/north-korea-missile-launches-1984-present/.

126 Vann H. Van Diepen, “North Korea’s Feb. 8 Parade Highlights ICBMs and Tactical Nukes,” 38 North, February 15, 2023, https://www.38north.org/2023/02/north-koreas-feb-8-parade-highlights-icbms-and-tactical-nukes/.

127 “Military Parade Marks 75th KPA Birthday,” KCNA, February 9, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/ item/2023/202302/news09/20230209-01ee.html.

128 “ICBM Launching Drill Staged in DPRK,” KCNA, February 19, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/ item/2023/202302/news19/20230219-01ee.html.

129 “Demonstration of Toughest Response Posture of DPRK’s Strategic Forces,” KCNA, March 17, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news17/20230317-01ee.html.

130 “On Root of Escalated Tension in Korean Peninsula,” KCNA, March 17, 2023, http://www.kcna. co.jp/item/2023/202303/news17/20230317-02ee.html.

131 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Guides Test-fire of ICBM Hwasongpho-18,” KCNA, July 13, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202307/news13/20230713-01ee.html.

132 “Clear Display of DPRK Strategic Forces’ Toughest Retaliation Will and Overwhelming Strength: Launch Drill of ICBM Hwasongpho-18 Conducted,” KCNA, December 19, 2023, http://www.kcna. co.jp/item/2023/202312/news19/20231219-01ee.html.

133 “Multiple Rocket Launching Drill by KPA,” KCNA, February 20, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/ item/2023/202302/news20/20230220-08ee.html.

134 “Strategic Cruise Missile Launching Drill Conducted,” KCNA, February 24, 2023, http://www.kcna.co. jp/item/2023/202302/news24/20230224-09ee.html.

135 “Nuclear Counterattack Simulation Drill Conducted in DPRK,” KCNA, March 20, 2023, http://www. kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news20/20230320-01ee.html.

136 “New IRBM Solid-fuel Engine Test Conducted in DPRK,” KCNA, November 15, 2023, http:// www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202311/news15/20231115-17ee.html.

137 “Underwater Launching Drill of Strategic Cruise Missiles Conducted,” KCNA, March 13, 2023, http:// www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news13/20230313-01ee.html.

138 “Important Weapon Test and Firing Drill Conducted in DPRK,” KCNA, March 24, 2023, http:// www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202303/news24/20230324-01ee.html.

139 “Underwater Strategic Weapon System Tested in DPRK,” KCNA, April 8, 2023, http://www.kcna. co.jp/item/2023/202304/news08/20230408-01ee.html.

140 “Respected Comrade Kim Jong Un Makes Congratulatory Speech at Ceremony for Launching Newly-Built Submarine,” KCNA, September 8, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202309/news08/ 20230908-02ee.html.

141 Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., Victor Cha and Jennifer Jun, “North Korea Launches New Ballistic Missile Submarine,” CSIS Beyond Parallel, September 11, 2023, https://beyondparallel.csis.org/north-korea-launches-new-ballistic-missile-submarine/.

142 “DPRK NATA’s Report on Successful Launch of Reconnaissance Satellite,” KCNA, November 22, 2023, http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2023/202311/news22/20231122-02ee.html.