8 Media and Reconstruction

How did the Japanese and foreign media cover the disaster wrought by the first atomic bombing in human history?

How did the Japanese and foreign media cover the disaster wrought by the first atomic bombing in human history?

Journalists in news organizations tried to spread word of the unprecedented conditions in Hiroshima City. They were also suffered from the atomic bombing, and telephone and telegraph services were interrupted. Reporters of various news organizations struggled hard to send out their first-hand reports of Hiroshima’s destruction. However, in the midst of unprecedented confusion, every one of these became “lost reports.” Sometimes these reports were not shared because their head offices could not immediately believe the massive scale of the damages, and other times the reports failed to reach offices entirely in the confusion.

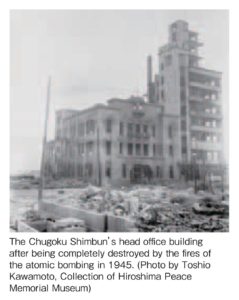

The Chugoku Shimbun had continued to issue the only newspaper in Hiroshima Prefecture at the time. The head office of the company was located some 900 meters east of the hypocenter. The building equipped with two rotary printing presses was completely incinerated in the bombing. The Chugoku Shimbun lost 114 employees or one out of every three employees of the head office. It is said that the first news report of the atomic bombing was a 6 p.m. radio broadcast on August 6. The national government and the military authorities hid the enormity of the damages from the atomic bombing and continued to tightly control the press in order to maintain morale among the people. Reporters were unable to report what they saw with their own eyes during the war. The reporters of the Chugoku Shimbun formed the “kudentai” (Verbal Reporting Corps) on August 7, to give verbal reports on emergency relief policies for victims of the bombing, temporary relief stations for the wounded, emergency provisions, and varlous other situations.

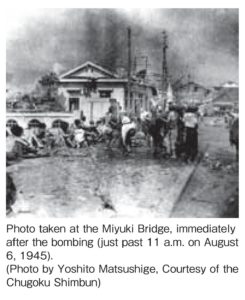

The photo below was taken by Yoshito Matsushige, a photographer at the Chugoku Shimbun, and shows A-bomb victims at the Miyuki Bridge, some 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. It was taken just past 11 a.m. on August 6. Matsushige was caught up in the bombing at his house in Midori-machi (currently Nishi Midori-machi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima City), some 2.7 kilometers southeast of the hypocenter. Fortunately, both he and his camera were unharmed. On the day of the bombing, he took five photos. These photos came to represent the atomic bombing of Hiroshima; but as the head office of the Chugoku Shimbun was completely burned, they could not run these photos in the newspaper. The first publication of these photos was on the page of the Yukan Hiroshima, dated July 6, 1946.

On August 14, 1945, the Japanese government accepted the Potsdam Declaration, and on the next day, August 15, the Showa Emperor’s imperial edict ending the war was broadcasted over the radio and the war came to an end. During the confusion that came with defeat, the strict press regulations from military authorities collapsed. On August 19, a photo of the ruins of Hiroshima was featured in newspapers, reporting the tragic scene nationwide. The people of Japan saw a part of the catastrophe wrought by the atomic bomb with their very own eyes. After reporting on the power of the atomic bomb, the press began reporting on the effects of radiation sickness.

As for the foreign media, Leslie Nakashima, a Japanese-American from Hawaii, sent out the first on-the-spot report from Hiroshima. Following Nakashima’s report, the American and European reporters who entered Hiroshima also ran their own reports. It was impossible for these reporters to miss the cruelty of the atomic bombing. At the same time, films recorded in Hiroshima were used to reinforce the legitimacy of the atomic bombing. However, after the occupation of Japan by the General Headquarters (GHQ) started, coverage of the atomic bombing was blocked again. The media has not completely thrown off its yoke and self-imposed regulations until Japan recovered its sovereignty in April 1952.

As for the foreign media, Leslie Nakashima, a Japanese-American from Hawaii, sent out the first on-the-spot report from Hiroshima. Following Nakashima’s report, the American and European reporters who entered Hiroshima also ran their own reports. It was impossible for these reporters to miss the cruelty of the atomic bombing. At the same time, films recorded in Hiroshima were used to reinforce the legitimacy of the atomic bombing. However, after the occupation of Japan by the General Headquarters (GHQ) started, coverage of the atomic bombing was blocked again. The media has not completely thrown off its yoke and self-imposed regulations until Japan recovered its sovereignty in April 1952.

Later, a national movement demanding to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs and a movement by A-bomb survivors to ask for support in the form of state reparations that began after the Bikini Atoll Incident in March 1954. The media responded to these movements by creating a foundation of the coverage of the atomic bombings and peace and dealt with the issue of nuclear weapons from a humanist perspective, as people are the ones who suffer from the effects of nuclear weapons. How did the people of Hiroshima survive life in the ruins? The only choice left for many citizens who suffered from the atomic bombing, and those who evacuated during the war and returned to a city that had been completely reduced to ruins, was to rebuild their livelihoods on their own. A census of the city’s population on November 1, 1945 shows that the population had dropped to one-third of its pre-bombing levels, leaving it at just under 140,000 people in the periphery of the city, which had escaped the fires.

How did the people of Hiroshima survive life in the ruins? The only choice left for many citizens who suffered from the atomic bombing, and those who evacuated during the war and returned to a city that had been completely reduced to ruins, was to rebuild their livelihoods on their own. A census of the city’s population on November 1, 1945 shows that the population had dropped to one-third of its pre-bombing levels, leaving it at just under 140,000 people in the periphery of the city, which had escaped the fires.

Even with the arrival of peace that followed defeat in the war, the rationing of staple foods did not increase but continued to decrease. People’s main staples were potatoes and thin rice gruel mixed with vegetables and wild grasses. Black markets sprouted up immediately and thrived in the ruins of Hiroshima. Just after the bombing, at around the end of August 1945, small stalls appeared in the area in front of Hiroshima Station. However, the black markets in Hiroshima City fell into rapid decline following police crackdowns, and gradually transformed into public and private markets.

Even with the arrival of peace that followed defeat in the war, the rationing of staple foods did not increase but continued to decrease. People’s main staples were potatoes and thin rice gruel mixed with vegetables and wild grasses. Black markets sprouted up immediately and thrived in the ruins of Hiroshima. Just after the bombing, at around the end of August 1945, small stalls appeared in the area in front of Hiroshima Station. However, the black markets in Hiroshima City fell into rapid decline following police crackdowns, and gradually transformed into public and private markets.

Before the war, Hiroshima was the prefecture with the largest number of people emigrating overseas. People of Japanese origin with ties to Hiroshima living across the globe quickly moved to support their hometown. Donations and relief goods were sent from Hiroshima Kenjinkai, the Hiroshima society in California, Hawaii, Brazil, Argentina, and elsewhere to support reconstruction efforts.

The creation of a professional baseball team in Hiroshima, the Hiroshima Carp, gave the people even more reasons to dream. Unlike the other teams, the Hiroshima Carp had no parent company, and its capital funds were contributed to by local governments and influential people in the government and private sectors. While they experienced serious financial difficulties from their start, the people of the city and the prefecture started supporters’ groups to support their local team through donations. People came to see the development of the team as tied with the progress of the reconstruction and development of Hiroshima.

The Korean War, which erupted in 1950, brought with it a boom in special procurement around the country. The people of Hiroshima began to feel tangible improvements in their daily lives, including having more food and clothing. At the same time, citizens had to make strenuous efforts to overcome strain and inconsistencies, to finally achieve a full reconstruction. These included forced evictions under the land readjustment projects of war damage reconstruction, an ever-increasing need for garbage and sewage treatment on the heels of a rising population, the redevelopment projects of the Moto-machi district, and more. As former Mayor Hamai, also called the “A-bomb Mayor,” once wrote: “We’ve lived through it.” This sentiment is shared by the citizens who made tremendous efforts to rebuild their lives from the ashes of the atomic

Inquiries about this page

Hiroshima Prefectural Office

Street address:10-52, Motomachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi, Hiroshima-ken, 730-8511

Tel:+81-(0)82-228-2111