“The Atomic Bomb Must Never Be Used for a Third Time on the World’s Cities” Kajiya Fumiaki, Association of Teachers Continuing to Tell Hiroshima’s Story

One can see skyscrapers, the lush greenery of the Hiroshima Peace Park, and Mount Takeda, dotted with numerous historical sites, as well as Ninoshima Island in the far distance. Standing in front of this peaceful landscape is Kajiya Fumiaki, of the Association of Teachers Continuing to Tell Hiroshima’s Story, holding a picture. The picture, painted in bright red by Mr. Kajiya, depicts the city of Hiroshima on that historical day. “Hiroshima was on fire. Hiroshima was burning bright red.” We asked Mr. Kajiya, who uses this picture to help tell Hiroshima’s story, about his own experience of living through the atomic bombing and what he wants to pass on to children.

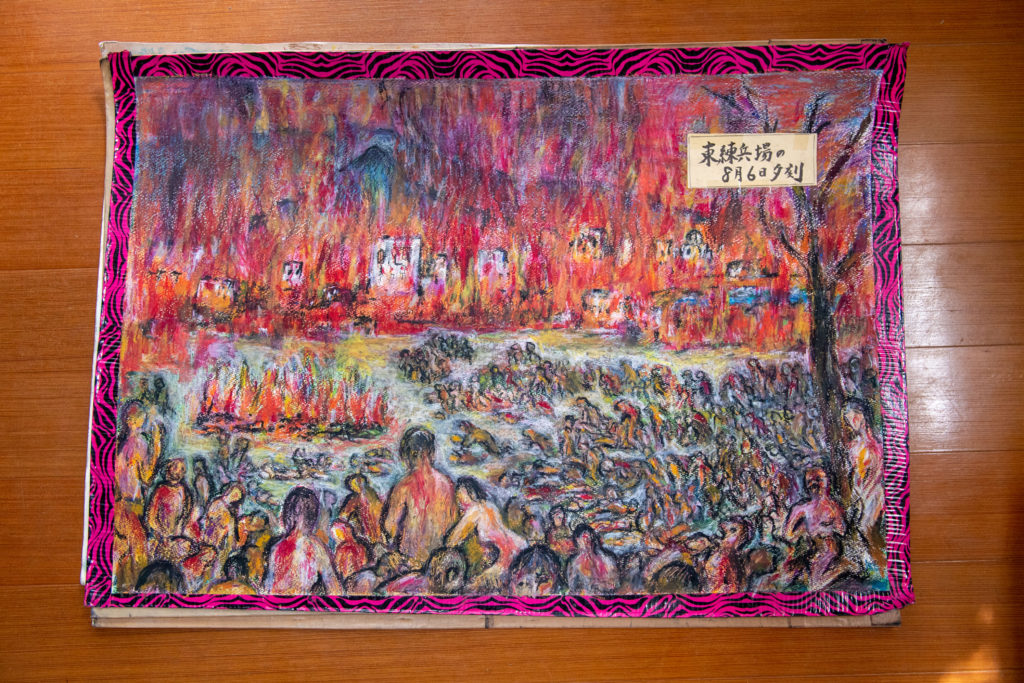

On the morning of August 6, 1945, I was a first-year student at Kojinmachi National School, located near Hiroshima Station, and I went to the scattered classrooms with my sister, who was two years older than me. As we began to clean up, a flash of light covered the whole area, and then, boom! The building collapsed instantly, hit by the heat rays and the shock wave, and I was trapped underneath. I managed to get out from under the collapsed building, and I ran and ran until I reached a mountain. From there, I looked down on the city of Hiroshima, which was burning bright red. The city rumbled loudly amid the fiery blaze until late in the evening.

In the evening, I went down the mountain to find my family and went to the East Drill Ground, which was located north of Hiroshima Station. The place was filled with people who did not look like humans. There were many pleading, “Give me some water, give me some water.” But I was six years old and there was nothing I could do. I also remember that there were dogs wandering around looking for their owners.

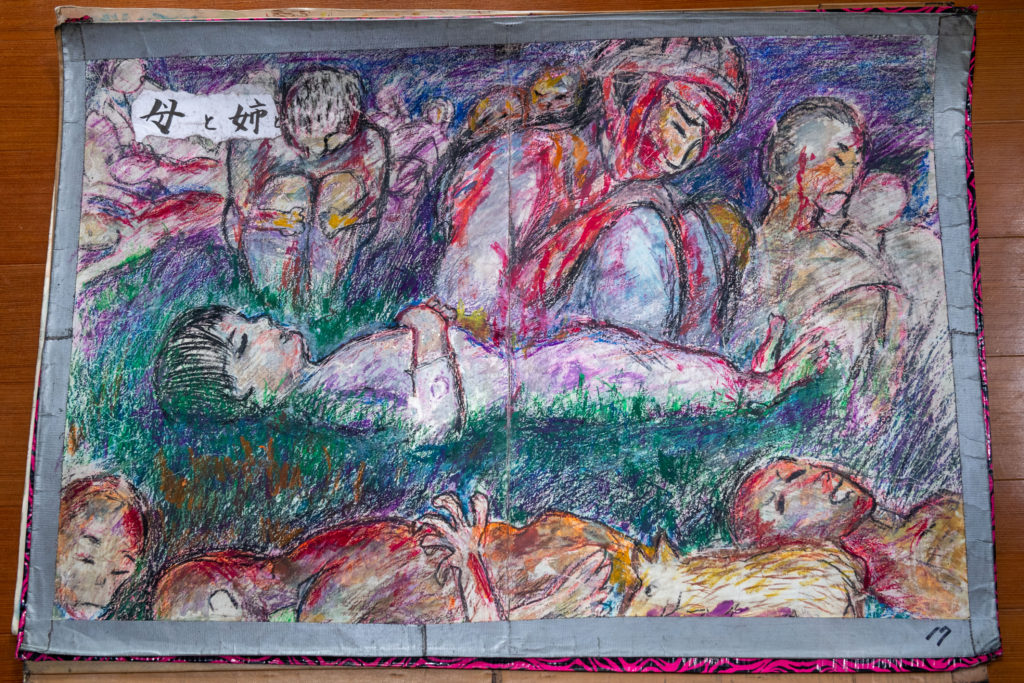

By sheer coincidence, I was reunited with my parents later that day. But my sister, who had been with me until morning, was dead. She had been evacuated out of the city to a relative’s house in what is now Kitahiroshima (in Hiroshima Prefecture), but when my mother went to bring her a change of clothes, she said, “Let me come home. If I die, then I die, but I want to be with my mom.” She was admonished and gave up for a while, but as my mother boarded the bus back to Hiroshima, she chased after my mother in tears. My mother couldn’t stand to see her like that, so she said, “If you die, I’ll die with you,” and brought her back to Hiroshima on August 2, days before the atomic bomb was dropped.

My mother always cried on August 6th. She said that she had let her daughter die…… My mother was wounded, with 50 or 60 shards of glass piercing her body, even her eyeball, but she lived to be 94 years old. I think she did her best and lived well. It was a time when just being together as a mother and a child was a risk to one’s life.

I was lucky enough to survive, and in the 1960s I became an elementary school teacher in Hiroshima. I knew that I wanted to share my experience of the atomic bombing with children in some way, but at that time, peace education in schools was rather ideological, with the union (the Japanese Teachers Union) coming up with all of the content for lectures, and even if there were teachers in the school who had experienced the bombing, there was no opportunity for them to give their testimonies.

As time went by, Hiroshima’s policy on peace education changed. In 1994, when I became the principal of Nagatsuka Elementary School, the teachers asked me to talk to the children about the atomic bombing experience. In order to make it easier to tell the story to the 1st-6th graders, especially the younger ones, I drew pictures to help tell the story. I drew pictures with pastels on large sheets of construction paper so that the children in the back of the room could see. That was how I started using pictures to tell about the experience of the atomic bombing. The first picture I drew was the scene of my sister’s death. I added more and more pictures over time and continue to use them today.

I felt that it really was meaningful for people who had experienced the atomic bombing to speak about it directly, so in 2001, after I reached retirement age and completed my commissioned job at the Hiroshima City Board of Education, I established the Association of Teachers Continuing to Tell Hiroshima’s Story. Since then, registered members of the group who are atomic bomb survivors have been sharing their experiences directly with children. For kindergartners and younger children, we use large hand and body gestures, and for older children, we explain in more detail the circumstances that led Japan to war and the damage caused by the nuclear bombing. My presentation lasts about 45 minutes, but the children listen to me very closely.

I try to convey the message, also drawn in the pictures, that “the atomic bomb must never be used for a third time on the world’s cities.” This is a part of a song that was often sung by people in Hiroshima until about 1950. Originally, the lyrics were “the atomic bomb must never be used for a third time on our cities,” but I changed the words to “on the world’s cities.”

Today, it is said that several countries possess nuclear weapons, and that there are about 13,000 nuclear weapons in the world. That means they have them, but they are not using them. World peace is maintained in a balance of tensions. If a modern atomic bomb were dropped on Hiroshima, it is said that the damage would cover a radius of 200km. The damage would impact not just the Chugoku region, but also parts of Shikoku and Kyushu, and considering the fallout damage, there would be nowhere to run in Japan if two or three bombs were dropped. If they are used, and more are used in retaliation, then forget about the survival of humanity, the whole world will be destroyed. It is difficult to get rid of the nuclear weapons we have anytime soon. Therefore, I think it is important for the world to agree that the use of nuclear weapons will not be tolerated.

We must not allow it to happen a third time. I would like to convey this message to as many children as possible. And I hope that when they become adults, they will tell it to their own children.

Kajiya Fumiaki

Born in Hiroshima in 1939. When he was in first grade, he was affected by the atomic bombing in the vicinity of Hiroshima Station. From 1962, he worked as an elementary school teacher and principal in Hiroshima City. He retired in March 1999. After working as a commissioned teacher, he established the Association of Teachers Continuing to Tell Hiroshima’s Story in 2001 and became its director.

Tags associated with this article