Building Column 5;Former Outpatient Wing of the Japan Post Hiroshima Teishin Hospital

Located near the Hakushima streetcar stop, this white box-like building is one of the few remaining pre-war modernist buildings in Hiroshima, and although you might walk past it thinking it is just another ordinary building, the building actually survived the atomic bombing.

The Japan Post Hiroshima Teishin Hospital (1) was founded for the employees and families of the former Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (the former government agency responsible for the postal service and communications), and was designed by Mamoru Yamada of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications’ Repair Division. At that time, the ministry had a large number of talented architects and produced many outstanding buildings. Yamada’s style shifted from period to period, but in the 1930s he focused on mastering European modernism, partly due to his visits abroad and partly due to the policies of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications as a whole.

The foundational idea underlying modernism is that function, not style, is what dictates form. Essential elements are logically arranged to form an architectural structure, without any ornamentation. While not particularly uncommon today since modernist architecture has become mainstream, it was an eye-catching, cutting-edge design in Japan at the time, in a time when traditional townhouses and Western-style buildings dominated the streets.

We will now take a look at the building as it stands today. It is a two-story reinforced concrete structure, and the third-floor sunroom that was originally there no longer exists. The exterior wall on the south side is lined with windows so large that the entire surface, except for the columns, is open, emphasizing that it allows outside light to enter the building. Rather than Japanese-style sliding doors, the window frames are raised, a style borrowed from Western-style buildings, but none of the original frames remain today.

Exterior south side wall

The old operating rooms on the first floor have been reconstructed as they were in the past, and visitors can tour the rooms if they make a request in advance. As the room was spared from the fire caused by the atomic bombing, the original tiles are still in place. What is unique about the rooms is their large bay windows, a design characteristic of the period, when lighting was still limited.

Bay window in an old operating room

Interior of an old operating room

Although much of the design details have been lost, we can still find traces of the ingenius design, for example, the corners have been slightly rounded off to soften the look of the space.

Walls and floors in an old operating room

The stairwell on the east side of the building is also open to visitors. This room has a distinctive vertical window, and part of the window frame from that time remains, apparently bent by the blast at the time of the atomic bombing.

Window of the stairwell on the east side

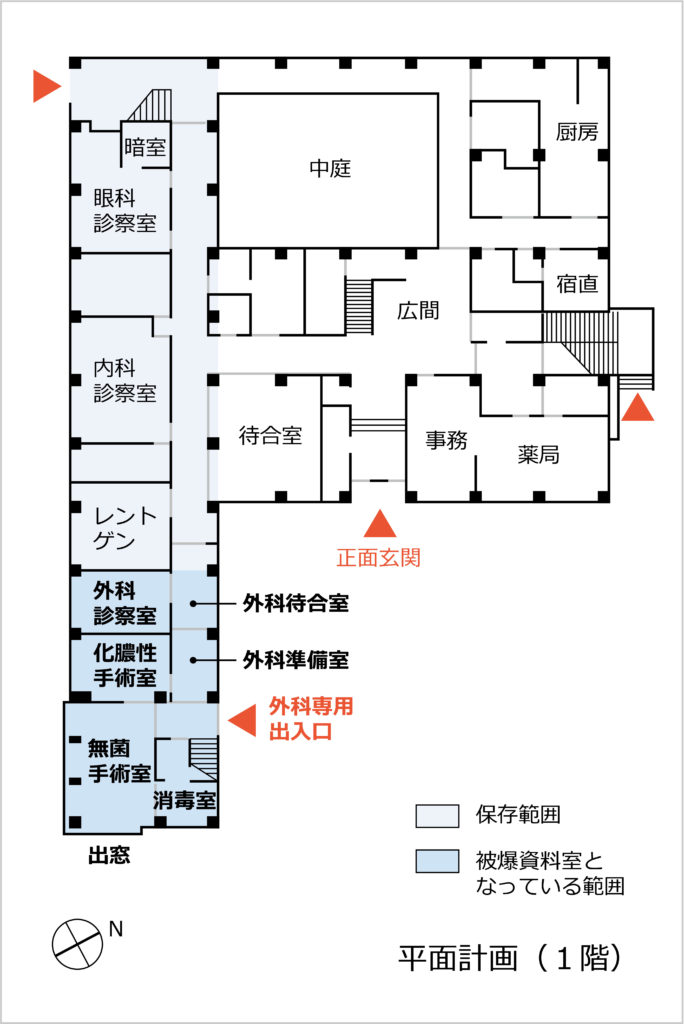

Let’s also examine the floor plan. The current building is rectangular in shape, but it was originally shaped like a hinge. The south side of the present building houses examination rooms on the first floor and hospital rooms on the second floor, while the north side, which has been destroyed, had the main entrance, office, pharmacy, kitchen, and other facilities. Placing the examination rooms and hospital rooms on the south side, which receives more light, was designed to facilitate a seamless and sanitary flow of patients from the reception area to the waiting area to the examination rooms. The current entrance was originally dedicated to the surgical department, with direct access to the operating rooms without having to go through the main entrance. This is a streamlined floor plan that is typical of modernism.

Floor plan (1st floor)

As advanced as this architecture was, it was severely damaged by the intense blast of the atomic bomb, resulting in the loss of window frames and medical equipment, and the destruction of the second floor hospital rooms by fire. In addition to the casualties among the staff, many survivors flooded into the hospital. Michihiko Hachiya, then director of the hospital, who was responsible for relief efforts, wrote a highly successful book, “Hiroshima Diary,” in which he described his own experience during the bombing and detailed the treatment of atomic bomb survivors.

After the bombing (from the collection of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

The building remained in use as a hospital until 1995, when it was designated as a piece of archive. The only remaining examples of Hiroshima’s numerous Posts and Telecommunications buildings are this one and the West Branch of the former Hiroshima Central Telephone Office (also designed by Mamoru Yamada), both of which are invaluable in conveying the reality of the atomic bombing and in preserving traces of the city’s architectural culture.

*Photographs in this article were taken by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Annotation

(1) The name of the hospital at the time of construction was Japan Post Hiroshima Teishin Clinic but it and was renamed to the Japan Post Hiroshima Teishin Hospital in 1942.

Building data

Location: 19-16 Higashi-Hakushima-cho, Naka-ku, Hiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture

Completion: 1935

Designed by: Mamoru Yamada, Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications

*Reservations are required for tours. For details and to make a reservation, please click here.

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/atomicbomb-peace/10169.html

References

“Regionality of Architectural Activities in Modern Japan” Ming Lee + Norioki Ishimaru, 2008

“Hiroshima’s Bombed Buildings Tell Their Stories,” City of Hiroshima + Association for the Study of Buildings Exposed to the Atomic Bombing, 1996

Profile of the author

Makoto Takata

Born in Hiroshima in 1978. Urban planner.

Representative of Archiwalk Hiroshima.

He promotes the appeal of architecture in Hiroshima through architectural open house events and the publication of architectural guidebooks. Publication: “Archimap Hiroshima”.

Tags associated with this article