I State of Healthcare and Medical Care between 1945 and 1955

1 Health & Medical Care Environment after the War

The war left the daily lives of Japanese citizens utterly in shambles. Along with the collapse of the economy and local infrastructure, combined with demobilized soldiers and repatriates returning from overseas, poor hygiene caused acute infectious diseases, tuberculosis, and other diseases to spread. On top of a severe shortage of healthcare professionals, medical facilities and medicine, the medical insurance system failed due to worsening inflation, leaving many people unable to receive any medical treatment when they became ill.

Most of the city was destroyed in the fire that followed the bombing. According to a record published by the City of Hiroshima, 300,000 to 310,000 civilians and 43,000 military personnel were exposed to the atomic bombing, and as of November 1945, about 130,000 people had died. In this way, the situation in Hiroshima was more dire than that in other cities.1) In urban areas, all medical institutions not made of reinforced concrete were destroyed. The remaining hospitals had also received extensive damage and could not continue to provide satisfactory medical services. This was further exacerbated due to the Air Defense Work Order, which had prohibited healthcare professionals from evacuating. A total of 2,168 out of the 2,370 healthcare professionals, including 270 of 298 physicians, who were in Hiroshima City at the time of the bombing were exposed to the atomic bombing, leaving many patients unable to receive medical treatment.2)

2 Survey of Deaths in Hiroshima after the War

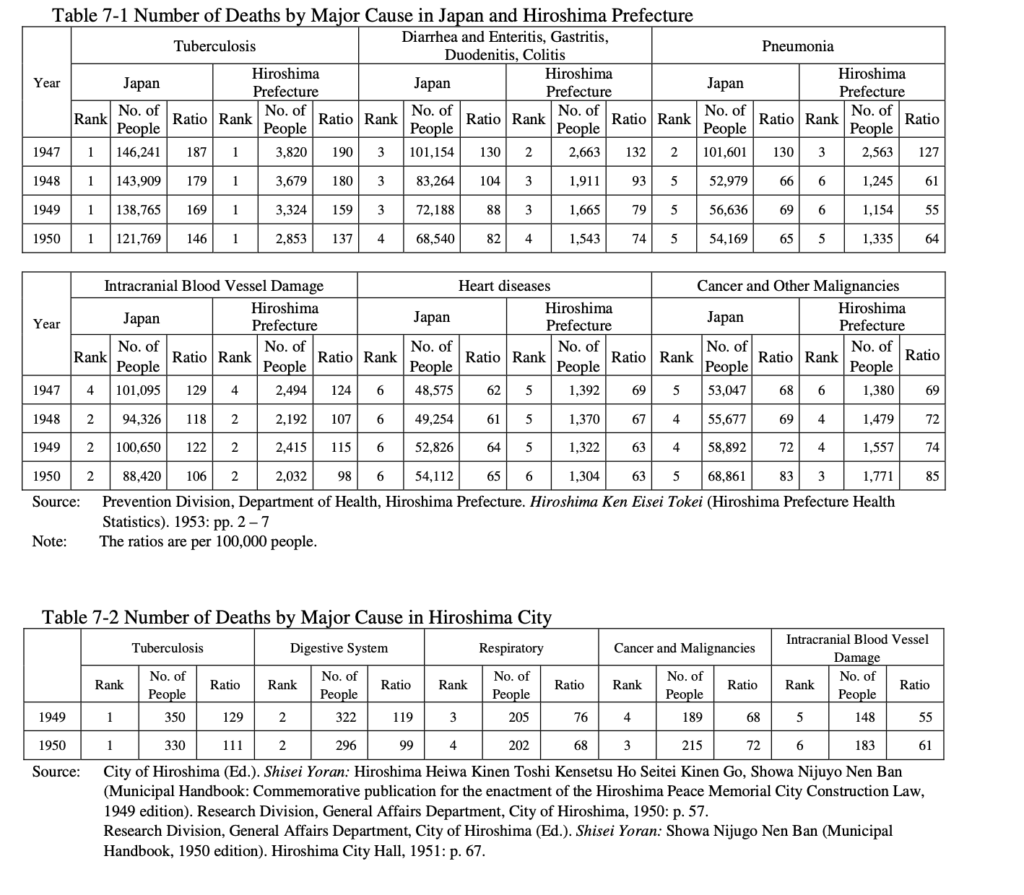

After 1947, the total deaths by major cause were tallied for the whole country, and after 1949 for Hiroshima Prefecture. The categorization of illnesses also differs slightly between the two.

Table 7-1 shows the numbers of deaths by main cause, providing evidence that trends in Hiroshima Prefecture were similar to that of the country as a whole. The mortality rate was 11.6 per 1,000 in 1949, which was the same as the national average.3) However, it should be noted that these results are only based on records from 1947 to 1950 so they do not include the statistics from 1945 and 1946, when most people died. Although the statistics from 1945 and 46 are not included, it is noteworthy that the mortality rate for cancer and other malignancies was slightly but consistently higher than the rest of Japan, though the number of deaths per 100,000 and the mortality rate were both lower than the rest of the nation for other illnesses.

As shown in Table 7-2, the leading cause of deaths in Hiroshima City was tuberculosis―the same as for the whole nation. Digestive system related deaths were high, while deaths caused by damage to intracranial blood vessels were low. Respiratory diseases, cancer, and malignancies were about the same level as the whole nation. The ratios for the five major causes of death were lower in Hiroshima City than those of the nation as a whole. All of these numbers come from a period after the worst period of the radiation effects of the atomic bomb, so they are not definitive.

3 Activities at Public Health Centers after the War

Acute infectious diseases, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases spread in Hiroshima Prefecture as well during the period of confusion immediately after the war. Under such circumstances, and despite severe financial constraints, countermeasures could be taken during this time (though not sufficiently) due largely to reformation of the medical and public health administration under the guidance of GHQ. Regional public health administration was dissociated from the police force, and a system was established that positioned the Ministry of Health and Welfare at the top, followed by prefectural public health departments, prefectural public health centers, and municipalities. Especially large was the role of public health centers, which became frontline institutions for handling public health.

On September 5, 1947, after being completely revised under GHQ’s guidance, the Health Center Law, was adopted (implemented January 1, 1948) and public health centers were tasked with managing public health in virtually all fields. In response to this new policy, Hiroshima Prefecture worked to improve the 19 prefectural public health centers that had been established by the end of the war. In May 1948, the “Establishment of Model Public Health Centers” (for the establishment of such centers in every prefecture) and in June the “Transfer of Jurisdiction over Public Health Centers to Cities” (for cities with populations over 150,000) were notified. With this, administration of the prefectural Hiroshima Public Health Center was transferred to the City of Hiroshima and the prefectural Kure Public Health Center, which was a model public health center, to the City of Kure on August 1. The reason that the prefectural Kure Public Health Center was designated as a model public health center is that the headquarters of the occupation forces were located there at that time.4)

While the Hiroshima City Public Health Center had a staff of only 31, the Kure City Public Health Center started with four divisions and a staff of more than 120. The Kure center immediately set to work creating a plan for the prevention of tuberculosis, venereal diseases, parasites, and trachoma, as well as a plan for health and nutrition for mothers and children.5) On one hand, under the strict guidance and support of the occupation forces and thorough sterilization, the number of patients recorded as having legally recognized infectious diseases had dropped from 1,650 in 1944 to 603 in 1945, to 397 in 1946, and to 147 in 1947. On the other hand, tuberculosis, venereal disease and other notifiable infectious diseases were rampant. This is thought to be the reason for the implementation of these plans.

Tuberculosis, especially, had a high number of patients (and deaths), with 1,523 in 1948 (472 deaths) and 1,755 in 1949 (433 deaths). The “Kure City Public Health Center Guidelines for Tuberculosis Measures” (five-year plan) was introduced in 1949, which implemented education on tuberculosis prevention measures; tuberculin and BCG vaccinations; photofluorography for persons with strong reactions on tuberculin tests; and recuperation guidance for sufferers. In 1955, the number of patients and that of deaths were down to 924 and 137 respectively.

For venereal diseases, the Kure City Public Health Center took action by establishing a venereal disease clinic in the Center on October 11, 1949, but the number of patients with venereal diseases was still over 2,000. The situation worsened to 3,916 patients in 1951 with the Korean War, and as many as 5,469 patients in 1952. Following this, the center ordered an estimated 3,000 habitual prostitutes to form five unions and to receive regular checkups. Those who would not receive checkups were patrolled four times a week with the help of the military police of the occupation forces, and citywide crackdown was conducted with the police two or three times a month.6) However, the number of the afflicted did not drop back down to the 2,000 range until the British Commonwealth Forces Korea had completely withdrawn in 1956.7)

4 Status of Medical Institutions and Activities after the War

Information containing the overall medical statistics for Hiroshima City before 1947 cannot be found. With regard to medical institutions in Hiroshima City in 1948, 1949, and 1950, the statistics show an increase in the number of hospitals (24 in 1948, 35 in 1949, 35 in 1950) and high fluctuations in the number of clinics (205 in 1948, 270 in 1949, 230 in 1950). Except for a drop in the number of dentists in 1949, healthcare personnel also steadily increased; physicians: 360 in 1948, 520 in 1949, 551 in 1950; dentists: 139 in 1948, 128 in 1949, 151 in 1950; nurses: 500 in 1948, 745 in 1949, 752 in 1950; midwives: 190 in 1948, 371 in 1949, 378 in 1950; public health nurses: 60 in 1948, 91 in 1949, 94 in 1950; pharmacists: 225 in 1948, 277 in 1949, 286 in 1950; and quasi-medical practitioners: 222 in 1948, 262 in 1949, 270 in 1950.8)

Hiroshima’s biggest medical institution, National Hiroshima Hospital, opened on December 1, 1945, following the closing of the Hiroshima Second Army Hospital’s branch hospitals, which had been established to move some of the hospital’s functions outside the city. Ten physicians, and 50 to 60 nurses and 200 inpatients were transferred to the hospital which was located on the premises of a company called Daiwabo in Ujina-machi, Hiroshima City. However, on December 5 orders were given from the occupation forces to vacate the hospital so that it could be used as a repatriation camp for Koreans in Japan. With no other choice, they moved operations to the empty barracks of the former army shipping training unit in Tanna-cho.9)

Under such circumstances, in early February 1946, the National Hiroshima Hospital were to be reopened to accept the sick and wounded as activities for the repatriation of Koreans would be completed by the end of March, and demobilization of military personnel and the repatriation of Japanese civilians would begin. From the beginning of March, the interior of the former Army Marine Headquarters building was renovated to be used as the headquarters of the hospital, three new temporary wards were built by the Ujina Repatriate Relief Bureau of the national government, and the Tanna-cho barracks were renovated, allowing them to accommodate 1,500 patients in total.

From April until late September 1946, 200 staff members dealt with anywhere between 500 to 1,000 patients disembarking from American and British hospital ships at a time. They performed cumbersome duties such as dividing and treating the patients. They were divided into those returning to their families, those transferred to other national hospitals, and those accommodated at the National Hiroshima Hospital. These patients included army personnel (1,416), navy personnel (496), and civilian repatriates (184)―2,096 people in total.10) It was reported that citizens in Hiroshima, especially A-bomb survivors, were given treatment afterwards. According to a document published in April 1947, the hospital had departments of internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, otorhinolaryngology, dermatology and urology, and dentistry.11)

The Japan Medical Treatment Corporation was established as a special corporation based on the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Order, which came into effect the day after it was promulgated on April 16, 1942, to expand medical care to increase the physical strength of Japanese people―especially by eradicating tuberculosis and ensuring all areas had access to doctors.12) The corporation supported the medical system during wartime, but on January 24, 1947, the Cabinet decided to disband it on April 1; and its 81 tuberculosis sanatoriums and 11 Shokenryo (tuberculosis sanatoriums for middle-aged and young patients potentially curable) were transferred to the care of the national government.13) With the promulgation of the Law regarding Dissolution and Liquidation of Medical Association, Dental Association, and Japan Medical Treatment Corporation on October 31 and its enactment on November 1, the corporation was finally dissolved and the corporation’s 180 hospitals and clinics were in principle transferred to the jurisdiction of prefectures and major cities.14)

The fiscal year 1944 medical facility income and expenditure survey (from April 1, 1943 to March 31, 1944) gives us a glimpse of the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation’s activities in Hiroshima Prefecture during the war (in this case, fiscal year 1944 is probably a mistype of fiscal year 1943). This survey mentions a tuberculosis sanatorium called Hataga Hospital (150 beds, total number of patients: 28,952) and Shokenryo in Kure (number of beds and total number of patients unknown), Onomichi (50 beds, 3,427 patients), and Oku (150 beds, 7,308 patients). However, the survey gives no information on the prefectural and the regional hospitals established and run by the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation in Hiroshima Prefecture.15)

After the war, the relief stations for A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima City were closed on October 5, 1945, and turned over to the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation. Of these, the relief station at Kusatsu National School (a primary school), run by staff members of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital (the hospital attached to the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical School), was renamed the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Kusatsu Hospital on February 1, 1946.16) The Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Yaga Hospital at Yaga National School was relocated and rebuilt in Iwahana in the same town, due to the “small and inadequate facilities on top of the serious disturbance it caused to children’s school education.” (Construction was scheduled to begin on August 1, 1946, and to be completed on March 31, 1947.)17)

On October 1, 1945, after taking over administration of the Hiroshima Army Kyosai Hospital (opened on November 3, 1942) in Ujina-cho 13-chome and the Army Hospital’s Inokuchi branch hospital, the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Ujina and Inokuchi branch hospitals were opened.18) The Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Kusatsu Hospital merged with the Corporation’s Ujina Hospital on June 1, 1947 and opened as the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Hiroshima Chuo Hospital, using Ujina Hospital’s facilities. The director was Iwano Kurokawa, who was director of the Kusatsu Hospital.19)

During this time, the board of directors of the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation decided on February 20, 1946 to close all Shokenryo that were experiencing financial difficulties by March 31. In Hiroshima Prefecture, the Kure Shokenryo (50 beds) was to be closed after having been destroyed by a fire, while the Onomichi Shokenryo (clinic with 50 beds) was to be converted into a regional hospital. On April 1, 1947, the Hataga Hospital (150 beds), Hara Sanatorium (188 beds), and Oku Shokenryo (150 beds) were to be transferred to prefectural government control. On November 1, the Corporation’s Hiroshima Chuo Hospital (a prefectural hospital), and regional hospitals including the Setoda Hospital, Kure Katayama Hospital, Yaga Hospital, Akitsu Hospital, as well as Chuo Hospital’s Inokuchi branch hospital and Tadanoumi Hospital were transferred to the jurisdiction of the prefectural government, under the circumstances explained above.21)

Hiroshima Prefecture accepted these hospitals in order to “strongly promote its healthcare policies to meet the needs of the residents of the prefecture.”22) Through negotiations with the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation, a contract was signed on March 23, 1948 to transfer the management of the seven hospitals and two clinics to Hiroshima Prefecture.23) And with the Prefectural Hospital and Prefectural Clinic Establishment and Management Ordinance enacted on March 31, these facilities were used to open the Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital, Inokuchi Prefectural Hospital, Prefectural Kosei Hospital (renamed from Yaga Hospital), Niko Prefectural Hospital (renamed from Kure Katayama Hospital), Akitsu Prefectural Hospital, Setoda Prefectural Hospital, Tadanoumi Prefectural Hospital, Toyota Prefectural Clinic, and Kobatake Prefectural Clinic on April 1.24)

Medical facilities in the city of Hiroshima received catastrophic damage from the atomic bombing, but the reconstruction was considered to be quicker than expected. This was made possible with the legacy of the army, as the National Hiroshima Hospital was opened as the successor to the Second Army Hospital, and the Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital utilized the facilities of the Hiroshima Army Kyosai Hospital. The role played by the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation must also be remembered. One example was the establishment of the Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital based on one of the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation hospitals. However, while there were improvements as most hospitals and clinics secured healthcare professionals, the facilities and medical equipment were still insufficient. Reconstruction still had a way to go.

Notes

1. Hiroshimashi Nagasakshi Genbaku Saigaishi Henshu Iinkai (Ed.). Hiroshima, Nagasaki no Genbaku Saigai (Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Damages of the Atomic Bombings). Iwanami Shoten, 1979: pp. 266, 274-275.

2. Hiroshimashi Ishikaishi Hensan Iinkai (Ed.). Hiroshimashi Ishikaishi: Dai Ni Hen (History of the Hiroshima City Medical Association, Vol. 2). Hiroshima City Medical Association, 1980: pp. 283 – 284.

3. Public Health Division, Department of Health, Hiroshima Prefecture (Ed.). Hiroshimaken Eisei Tokei Nenpo: Dai Ni Go, 1949 Nendo (Annual Report of Statistics on Public Health in Hiroshima Prefecture, No.2, Fiscal 1949). p. 23.

4. Kureshishi Hensan Iinkai. Kureshishi: Dai Nana Kan (History of the City of Kure, Vol. 7). City of Kure, 1993: pp. 802 – 803.

5. Department of Health, City of Kure. Showa Nijusan Nendo Kureshi Kansa Shiryo (Audit Document of Kure City, Fiscal Year 1948).

6. Health and Disease Prevention Division, Public Health Center, City of Kure, Teirei Kansa Shiryo, 1952 Nendo (Regular Audit Document, Fiscal 1952).

7. For information on medical treatment of the occupational forces, see: Chida, Takeshi. Eirenpogun no Nihon Shinchu to Tenkai (Occupation of Japan by the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces and their Deployment). Ochanomizu Shobo, 1997.

8. City of Hiroshima. Shisei Yoran: Showa Nijusan Nendo Ban (Municipal Handbook, Fiscal 1948 Edition). p. 45. City of Hiroshima. Shisei Yoran: Showa Nijugo Nendo Ban (Municipal Handbook, Fiscal 1950 Edition). p. 69.

9. Yoshimura, Minoru (1st Director of the National Hiroshima Hospital). “Hirohsima Rikugun Byoin no Genbaku Shori” (Hospital Practices of the Hiroshima Army Hospital after the Atomic Bombing). In National Kure Hospital (Ed.). Kokuritsu Kure Byoin Soritsu Jugo Nen no Ayumi (15-Year History of the National Kure Hospital). 1971: pp. 17 – 21. Most information on the National Hiroshima Hospital comes from this reflection.

10. Medical Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Health and Welfare (Ed.). Kokuritsu Byoin Ju Nen no Ayumi (10-Year History of National Hospitals). 1955: pp. 7, 14, 99.

11. Motoki, Bunsen (Ed.). Hiroshima Yoran (Brief Description of Hiroshima). Yukan Minsei Shimbunsha, 1947: p. 287.

12. Nihon Iryodanshi (History of the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation). Japan Medical Treatment Corporation. 1977: p. 37.

13. Ibid., pp.90 – 95.

14. Ibid., pp.104 and 178 – 183.

15. Hiroshima Prefecture Branch, Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1945 a). “Ujina Byoin Ikken, Ki 1945 Nen Ku Gatsu” (Documents relating to the Ujina Hospital from September 1945). Archived at Hiroshima Prefectural Office.

16. Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital. Soritsu Hyakuniju Nen Kinenshi (120th Year Commemorative Publication). 1999: p. 38.

17. Hiroshima Prefecture Branch, Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1945 a). op. cit.

18. City of Hiroshima (Ed.). Hiroshima Genbaku Sensaishi: Dai Ikkan, Dai Ippen Sosetsu (Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, Vol. 1, Part 1, Overview). 1971: pp. 484 – 490. Hiroshima Prefecture Branch, Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1945 a). op. cit.

19. Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital. op. cit., p. 38. Hiroshima Prefecture Branch, Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1945 a). op. cit.

20. Hiroshima Prefecture Branch, Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1945 a). op. cit.

21. Japan Medical Treatment Corporation (1977). op. cit., pp.171 – 183.

22. Planning Division, Hiroshima Prefecture (Ed.). Kensei to Sono Taisho no Bunseki Hiroshima Kensei ni Kansuru Jisso Hokokusho: Dai Ni Hen (Analysis of Prefectural Policies and their Target – Report on Realities of Hiroshima Prefectural Policies, Vol. 2). Setonaikai Bunko, 1948: p. 78.

23. Contract between the governor of Hiroshima Prefecture and the Japan Medical Treatment Corporation Liquidator, dated March 23, 1948 in Medical Affairs Division, Hiroshima Prefecture. Tochi Tatemono Kankei Keiyakusho (Kenritsu Byoin) (Documents regarding the contract on site and buildings of Prefectural Hospital). Collection of Hiroshima Prefectural Archives.

24. Hiroshima Kenpo (Hiroshima Prefecture official gazette). March 31, 1948.