Hiroshima Report 2024(2) IAEA Safeguards Applied to the NPT NNWS

A) Conclusion of IAEA Safeguards Agreements

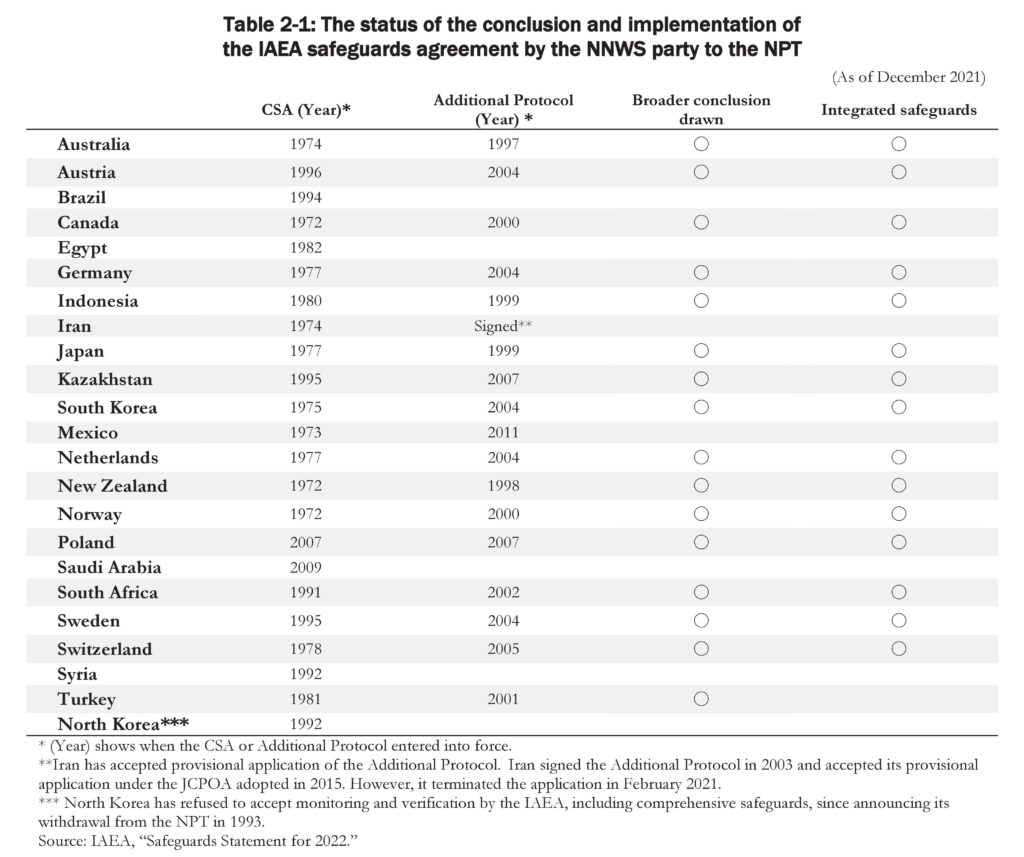

To prevent and detect the diversion of nuclear materials from peaceful purposes to nuclear weapons and other nuclear explosive devices, Article III-1 of the NPT obliges NNWS to conclude and implement a comprehensive safeguards agreement with the IAEA and to accept its safeguards. As of May 2023, four NPT non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) have yet to conclude CSAs with the IAEA.49

In accordance with the strengthened safeguards system in place since 1997, an NPT NNWS or any other state may also conclude with the IAEA an Additional Protocol to its safeguards agreement, based on a model document known as INFCIRC/540. As of May 2023, 135 NPT NNWS have ratified Additional Protocols. Iran started provisional implementation of the Additional Protocol in January 2016, but terminated its application in February 2021 in response to U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA.

A state’s faithful implementation of the Additional Protocol, along with the CSA, allows the IAEA Secretariat to draw a so-called “broader conclusion” that “all nuclear material in the State has remained in peaceful activities.” This conclusion states that the Agency finds no indication of diversion of declared nuclear material from peaceful nuclear activities, misuse of the facilities for purposes other than those for which it was declared, or the presence of any undeclared nuclear material or activities in that country. (At the end of 2022, such a conclusion was drawn for 74 countries.) Subsequently, the IAEA implements so-called “integrated safeguards,” a term defined as the “optimized combination of all safeguards measures available to the Agency under [CSAs] and [Additional Protocols], to maximize effectiveness and efficiency within available resources.” According to the IAEA’s “Safeguards Statement for 2022,” published in 2023 and describing the situation in 2022, as of the end of 2022, 69 NNWS have applied integrated safeguards.50

The current status of signature and ratification of the CSAs and the Additional Protocols and implementation of integrated safeguards by the NPT NNWS studied in this project is presented in Table 2-1. In addition to the IAEA safeguards, EU countries accept safeguards conducted by EURATOM, and Argentina and Brazil conduct mutual inspections under the bilateral Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC).51

In the resolution, titled “Strengthening the Effectiveness and Improving the Efficiency of Agency Safeguards” adopted in September 2023, the IAEA General Conference called on all States with unmodified Small Quantity Protocols (SQPs) to either rescind or amend them, and stated that the amended SQPs for 78 countries have entered into force as of September 2023.52 Meanwhile, among countries that have expressed their intentions to introduce nuclear energy, Saudi Arabia has not yet accepted an amended SQP.53 At the IAEA General Conference in September 2023, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Energy Abdulaziz Bin Salman stated, “[T]he Kingdom has decided recently to rescind the Small Quantities Protocol and implement the full Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement. The Kingdom is working, within the framework of its national ecosystem, to establish the necessary mechanisms for this full implementation, following best international practices and experiences.”54 In November, IAEA Director General Grossi said that a nuclear research reactor being built for Saudi Arabia by an Argentine company was almost complete, and that the IAEA and Saudi Arabia had been discussing the necessary inspections.55

B) Compliance with IAEA Safeguards Agreements

According to the “Safeguards Statement for 2022” published in 2023, as of the end of 2022, of the 134 countries to which both CSAs and the Additional Protocols are applied (not including Iran suspending provisional application of the Additional Protocol in 2021), the IAEA concluded that all nuclear materials remained in peaceful activities for 74 countries. For the remaining 60 countries, evaluations regarding the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities for each of these states remained ongoing, and the IAEA concluded only that declared nuclear material remained in peaceful activities. For 46 countries with a CSA but with no Additional Protocol in force, the Agency concluded only that declared nuclear material remained in peaceful activities.56

North Korea

In an annual report titled the “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” in September 2022, the IAEA Director-General reported: “From the end of 2002 until July 2007, the Agency was not able, and since April 2009 has not been able, to implement any safeguards measures in the DPRK.”57 The IAEA also reported on the state of play of North Korea’s nuclear-related facilities during August 2022 through August 2023 via an analysis of public information and satellite images, for instance:

➢ Uranium mining and concentration: there were indications of ongoing mining, milling and concentration activities at the Pyongsan Uranium Mine and the Pyongsan Uranium Concentrate Plant, consistent with activities observed by the Agency during previous years.

➢ Uranium enrichment facility in Yongbyon: the Agency observed indications that the reported centrifuge enrichment facility at Yongbyon continued to operate. As previously reported, between September 2021 and May 2022, a new annex to this facility was constructed, thereby increasing the overall floor area by approximately one third. There were indications during the reporting period that activities related to uranium enrichment had commenced within the new annex.

➢ Kangson complex: there were indications of ongoing activities at this complex.

➢ 5MW graphite reactor: indications of the operation of the 5MW(e) Experimental Nuclear Power Plant, including the discharge of cooling water, continued to be observed. However there were short periods in late-September 2022, mid-November 2022, late-March 2023 and mid-April 2023, when there was no cooling water discharge. Intermittent shutdowns are consistent with observations of past reactor operating cycles.

➢ Other graphite reactors: construction of the 50MW(e) Nuclear Power Plant at Yongbyon and the 200MW(e) Nuclear Power Plant at Taechon was halted during the 1994 Agreed Framework and has since not been restarted.

➢ Light Water Reactor (LWR) under construction: an increase in the level of activity around the Light Water Reactor (LWR) was observed throughout the reporting period. A new channel for the southern cooling water outlet was excavated in October 2022 and indications of possible tests of the LWR’s cooling water systems were observed more frequently, and for longer duration, than in previous reporting periods. The Agency did not observe indications of the operation of the LWR and, based on the information currently available, it is not possible for the Agency to estimate when the reactor could become operational. During the reporting period, three new buildings were constructed in the immediate vicinity of the LWR. In addition, as previously reported, construction started on a new group of buildings south of the LWR compound in August 2021, possibly to support the fabrication or maintenance of reactor components. The construction of this group of buildings was externally complete by December 2022. Further south of the LWR compound, construction of another industrial-type building commenced in March 2023. The purpose of this building has not been determined by the Agency.

➢ Radiochemical Laboratory (reprocessing): the steam plant that serves the Radiochemical Laboratory was observed by the Agency to have operated from late-April to late-September 2022, although only intermittently. From late-June 2023 to the end of the reporting period the steam plant was again observed to be operating intermittently. The observed operation of the steam plant is consistent with waste treatment or maintenance activity at the Radiochemical Laboratory. In March 2023, the Agency observed that the soil and vegetation covering a radioactive waste storage location situated north of the Radiochemical Laboratory had been removed, exposing the liquid waste storage tanks and solid waste storage compartments. Near a second waste storage location, a building located east of the Radiochemical Laboratory, small-scale excavation was observed in late June 2023.

The IAEA stated, “Once a political agreement has been reached among the countries concerned, the Agency is ready to return promptly to the DPRK, if requested to do so by the DPRK and subject to approval by the Board of Governors. … During the reporting period, the Agency has continued to maintain its enhanced readiness to return to the DPRK and has undertaken, inter alia, the following activities:”58

➢ Continued its collection and analysis of safeguards relevant open source information on the North Korea’s nuclear program;

➢ Increased its collection and analysis of a wide range of high-resolution commercial satellite imagery, both optical and radar, to monitor the North Korea’s nuclear program;

➢ Maintained the equipment and supplies necessary to ensure that the Agency is prepared to promptly initiate verification and monitoring activities in North Korea;

➢ Conducted training of inspectors to maintain enhanced readiness to return to North Korea; and

➢ Continued to review and document the Agency’s knowledge of the North Korea’s nuclear program, including through 3D modelling of facilities, information integration using a geospatial information system (GIS), and knowledge management activities, to ensure the Agency’s experience from past activities in North Korea is preserved.

Iran

Verification and monitoring

In accordance with a domestic law enacted in December 2020, Iran in February 2021 stopped implementing the verification measures in the JCPOA that went beyond the requirements of Iran’s full-scope safeguards agreement with the IAEA. The IAEA Director-General’s report in November 2023 reported that the following verification and monitoring activities have not been implemented since February 23, 2021:59

➢ Monitoring or verifying Iranian production and stocks of heavy water;

➢ Verifying that use of shielded cells at two locations, referred to in the decision of the Joint Commission of January 14, 2016 (INFCIRC/907), are being operated as approved by the Joint Commission;

➢ Implementing continuous monitoring to verify that all centrifuges and associated infrastructure in storage remain in storage or have been used to replace failed or damaged centrifuges;

➢ Performing daily access upon request to the enrichment facilities at Natanz and Fordow, including to monitor Iran’s production of stable isotopes;

➢ Verifying in-process low enriched nuclear material at enrichment facilities as part of the total enriched uranium stockpile;

➢ Verifying whether or not Iran has conducted mechanical testing of centrifuges as specified in the JCPOA;

➢ Monitoring or verifying Iranian production and inventory of centrifuge rotor tubes, bellows or assembled rotors; verifying whether produced rotor tubes and bellows are consistent with the centrifuge designs described in the JCPOA; verify whether produced rotor tubes and bellows have been used to manufacture centrifuges for the activities specified in the JCPOA; verifying whether rotor tubes and bellows have been manufactured using carbon fiber which meets the specifications agreed under the JCPOA;

➢ Monitoring or verifying the uranium ore concentrate (UOC) produced in Iran or obtained from any other source; and whether such UOC has been transferred to UCF; and

➢ Verifying Iran’s other JCPOA nuclear-related commitments, including those set out in Sections D, E, S and T of Annex I of the JCPOA.

Iran has also continued to refuse, inter alia: implementation of the modified Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements to Iran’s Safeguards Agreement; provisional application of the Additional Protocol; and access to the data from its on-line enrichment monitors and electronic seals, or access to the measurement recordings registered by its installed measurement devices. The IAEA report in November also pointed out that “[t]he situation was exacerbated in June 2022 by Iran’s decision to remove all of the Agency’s JCPOA‑related surveillance and monitoring equipment.”

In the meantime, Iran and the IAEA agreed in March 2023 to reinstall surveillance cameras at Iran’s nuclear facilities, and the IAEA reported in May that they had been installed at workshops in Esfahan where centrifuge rotor tubes and bellows are manufactured.60

On September 16, IAEA Director-General Grossi criticized Iran, stating:

Today, [Iran] informed me of its decision to withdraw the designation of several experienced Agency inspectors assigned to conduct verification activities in Iran under the NPT Safeguards Agreement. This follows a previous recent withdrawal of the designation of another experienced Agency inspector for Iran. … With today’s decision, Iran has effectively removed about one third of the core group of the Agency’s most experienced inspectors designated for Iran.61

Iranian Foreign Ministry argued that the measure mentioned above was a countermeasure to abuse of the IAEA for political purposes by the United States, France, Germany and the United Kingdom.62 President Raisi also said, “We have no problem with the inspections but the problem is with some inspectors … those inspectors that are trustworthy can continue their work in Iran.”63

Iran also asserted that it had properly accepted IAEA safeguards, stating the following at the NPT PrepCom:

According to the latest Safeguards Implementation Report, the IAEA inspectors performed 448 inspections in Iran in 2022, which is more than the inspections conducted in Japan and Canada combined. Without Iran’s good-faith cooperation, it is not possible for the IAEA to perform this unprecedented level of verification activities in Iran. Iran deserves to be commended for providing this level of cooperation with the IAEA. It is essential that the IAEA conducts its verification activities in an indiscriminate, impartial and independent manner in order to uphold the credibility of the Agency as its biggest asset. The Agency must resist external pressures to manipulate its agenda. The focus of the IAEA on investigating the so- called outstanding safeguards issues, which are in fact 20-year-old allegations with no proliferation risk, will certainly not serve the Agency and the safeguards system. It has so far contributed only to the stated objective of those who are seeking to kill the JCPOA.64

Alleged undeclared activities

Iran continues to implement its comprehensive safeguards measures. However, the issue regarding the existence of past undeclared activities remains unresolved.

In a report to the IAEA Board dated February 23, 2021, the IAEA Director-General summarized the Agency’s assessment of the presence of undeclared nuclear material and activities at four sites that may have been associated with Iran’s 1989-2003 clandestine and systematic nuclear program (AMAD Plan). At one of the sites (reported elsewhere to be a warehouse at Turquzabad), environmental sampling revealed artificially-produced natural uranium particles, indicating that uranium conversion may have taken place, as well as low-enriched uranium (LEU) containing U-236 and depleted uranium with a slightly lower proportion of U-235 than natural uranium. At other two sites (Varamin and Marivan), analysis of environmental sampling indicated the presence of artificially produced uranium particles. The IAEA assessed that the remaining site (Lavisan-Shian) was not worth complementary access because it had been extensively cleared and traces had been removed.65

In its “Safeguards Statement in 2022,” the IAEA reported, “During 2022, despite the Agency’s continued efforts to engage [Iran] in order to resolve outstanding safeguards issues related to the presence of uranium particles of anthropogenic origin at locations in Iran not declared to the Agency, limited progress was made. Unless and until Iran clarifies these issues, the Agency will not be able to provide assurance about the exclusively peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear programme.”66

Iran announced at the end of July 2023 that it had submitted new details to the IAEA regarding two sites near Tehran, where inspectors had traces of manmade uranium.67 Despite this development, little progress was made towards resolving the issue. Consequently, on September 14, a joint statement by 63 countries68 was issued, which stated, “We call upon Iran to act immediately to fulfill its legal obligations to address the following issues identified by the Director General”:69

➢ The outstanding safeguards issues in relation to nuclear material detected at undeclared locations in Iran, including informing the Agency of the current location(s) of nuclear material and/or contaminated equipment;

➢ The discrepancy in the amount of nuclear material verified by the Agency at the Esfahan Uranium Conversion Facility (originating from the Jabr Ibn Hayan Laboratories), compared to the amount declared by Iran; and

➢ Iran’s implementation of modified Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements to its Safeguards Agreement, including the provision of the required early design information.

Syria

As for Syria, the IAEA assessed that the facility at Dair Alzour, which was destroyed by an Israeli air raid in September 2007, was very likely a clandestinely constructed, undeclared nuclear reactor. Although the IAEA has repeatedly called on Syria to cooperate fully with the Agency so as to resolve the outstanding issues, Syria has not responded to that request.70

In the meantime, the IAEA reported that inspections were carried out at the Miniature Neutron Source Reactor facility near Damascus and a location outside facilities (LOF) in Homs in 2022; and that it found no indication of diversion of declared nuclear material from peaceful activities.71

Acquiring naval nuclear propulsion by NNWS

Regarding acquisition of naval nuclear propulsion (specifically, for nuclear submarines) by NNWS, at the AUKUS (Australia-UK-U.S. Security Cooperation Partnership) summit meeting on March 13, 2023, detailed plans were disclosed in terms of the provision of nuclear submarines to Australia. This includes the delivery of three U.S. nuclear submarines to Australia in the early 2030s, and the United Kingdom will deliver its first nuclear-powered attack submarine SSN-AUKUS to the Royal Navy in the late 2030s.72 In May, the IAEA Director-General’s report outlined developments in the AUKUS initiative and ongoing discussions between the three countries and the IAEA.73

China repeatedly criticized the AUKUS on various occasions. In its working paper submitted at the NPT PrepCom in 2023, China claimed that:

The naval nuclear propulsion reactors and their associated nuclear material to be transferred by the US and the UK to Australia cannot be effectively safeguarded under the current IAEA safeguards system. Therefore there is no guarantee that the nuclear material thus transferred will not be diverted to the production of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.

… The three countries and the IAEA have no authority to interpret Article 14 of CSA and its application. There’s a huge international divergence on the application of Article 14, which has never been applied before. The international community is still far from reaching consensus on the definition of “non-peaceful activities” and “non-proscribed military activity” as well as on the scope and procedure for non-application of safeguards. In history, the formation, modification, explanation and execution of all kinds of safeguards agreements, whether CSAs, APs or SQPs, are all negotiated and decided by all the IAEA member states, and approved by the Board of Governors. Thus the explanation of Article 14 of CSA can be no exception. In 1978, the then-Director General made it clear in his exchange of letters with the Australian side (GOV/INF/347) that the Board of Governors had taken no opportunities to explain Article 14 and relevant procedures because no parties of NPT seek for the application of it. This fully proves that it shall be the Board of Governors to interpret Article 14 and its application rather than the Secretariat of the IAEA.

It will set a bad precedent if Australia invokes Article 14 for non-application of safeguards. The trilateral cooperation on nuclear-powered submarines involves large quantities of weapon-grade HEU. If Australia seeks non-application of safeguards, new arrangements for non-nuclear-weapon State fulfilling safeguards obligation will be created. That means part of its nuclear activities will be under IAEA safeguards of the IAEA while large quantities of HEU will be out of safeguards. Such cooperation will open the “Pandora’s box” and other countries may follow suit, severely undermining the international nuclear non-proliferation regime, and negatively impact the solution of regional nuclear hotspot issues.

… The trilateral cooperation on nuclear-powered submarines safeguard involves complex political, legal and technical questions, and has a direct bearing on the authority, integrity and effectiveness of the NPT, and thus is closely related to the interests of all IAEA member States. All the IAEA member states shall be allowed to discuss the issue through a transparent, open and inclusive intergovernmental process, and make decisions by consensus according to the historical practices of strengthening the safeguards system. The three countries shall not start nuclear-powered submarine cooperation before all parties reach consensus. The Secretariat of the IAEA shall not negotiate and conclude safeguards arrangements with the three countries arbitrarily.74

Russia also opposed the acquisition of nuclear submarines by Australia under AUKUS, stating:

We disapprove of the AUKUS trilateral partnership. It creates a fundamentally new geopolitical situation in the Asia-Pacific region. Within the partnership, an infrastructure of nuclear-weapon States, which can later be used to deploy nuclear weapons, is being established in a non-nuclear-weapon State that is also a NWFZ country. This produces an additional factor of instability that undermines nuclear disarmament efforts. In addition, this partnership involving the transfer of material that is not likely to be under comprehensive IAEA safeguards, while not violating the Safeguards Agreement, sets a precedent that could be used by other States in the future. This leads to weakening the NPT regime.75

Among the NNWS, Indonesia argued, “It must be recognized that challenges may arise from the potential dual-use nature of this technology, where the same advancements can be applied to the development of nuclear weapons and weakening the safeguards regime.”76 Egypt also expressed its concerns, stating: “Nuclear partnerships that involve the transfer of large quantities of unsafeguarded weapon-grade fissile material from [NWS] to any NNWS pose an unprecedented threat to the credibility and effectiveness of the nuclear non-proliferation regime and set precedents that will have far-reaching ramifications on the IAEA Safeguards System. The impact of these new types of nuclear partnerships, such as the AUKUS agreements, needs to be closely examined by the Conference.”77

On the other hand, Australia, which has reiterated that it has no intention of acquiring nuclear weapons,78 responded by saying, “In regard to Australia’s acquisition of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines, we will continue to engage openly and transparently with the IAEA on the development of a non-proliferation approach that meets the highest non- proliferation standard and allows the IAEA to continue to meet its technical safeguards objectives.”79 The AUKUS also submitted a working paper to the 10th NPT RevCon in 2022, and argued that it is neither in violation of its nonproliferation obligations nor any possibilities for nuclear proliferation.80 In the meantime, Australia has not specified what is meant by the “highest nonproliferation standard” to which it refers, or whether this standard entails additional measures beyond those stipulated in the Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement and Additional Protocol.

Brazil, which had launched construction of the first NNWS’s nuclear submarine, stated at the NPT PrepCom, “Nothing in the NPT precludes the development of naval nuclear propulsion. Furthermore, such activities are explicitly characterized as non-proscribed by all comprehensive safeguards agreements. Naval nuclear propulsion is, therefore, a peaceful use of nuclear energy. Consequently, no preconditions for the exercise of this right by non-nuclear-weapon States should be countenanced, beyond the obligations established by the IAEA safeguards regime.” It also argued: “In pursuing the legitimate goal of naval nuclear propulsion, Brazil is committed to transparency and open engagement with the IAEA, ensuring the Agency’s ability to fulfil its statutory non-proliferation mandate, as well as to keeping IAEA Member States informed about relevant developments.”81

Issues concerning Ukraine

Ukraine has adhered to its Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement and Additional Protocol with the IAEA. According to the IAEA Safeguards Statement 2019, integrated safeguards were applied to Ukraine. While the Safeguards Statement 2020 stated that the broader conclusion could not be drawn for Ukraine, the United States and the EU noted that this was not Ukraine’s fault, but rather that Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the activities of Russian-backed armed groups in eastern Ukraine prevented the IAEA from obtaining the information and access necessary to draw a broader conclusion.82

In 2022, the IAEA’s safeguards implementation was repeatedly challenged by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its armed attack and occupation of the Chornobyl and Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plants. However, the IAEA reported in its Safeguards Statement 2022 as following: “The armed conflict in Ukraine, which began in late February 2022, created unprecedented challenges for the Agency in the implementation of safeguards in Ukraine under the CSA (INFCIRC/550) and the AP (INFCIRC/ 550/Add.1). Nevertheless, the Agency continued to undertake its vital verification role in Ukraine throughout the year and was able to conduct sufficient in-field verification activities necessary to draw the safeguards conclusion for Ukraine for 2022.”83

In the resolution adopted at the IAEA General Conference in September 2023, titled “The safety, security and safeguards in Ukraine,” the IAEA Board of Governors “[called] for the urgent withdrawal of all unauthorized military and other unauthorized personnel from Ukraine’s [Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant (ZNPP)] and for the plant to be immediately returned to the full control of the competent Ukrainian authorities consistent with the existing license issued by the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU) to ensure its safe and secure operation and in order for the Agency to conduct safe, efficient, and effective safeguards implementation, in accordance with Ukraine’s comprehensive safeguards agreement and additional protocol.”84

49 IAEA, “Status List: Conclusion of Safeguards Agreements, Additional Protocols and Small Quantities Protocols,” May 3, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/20/01/sg-agreements-comprehensive-status.pdf. All of these four countries possess a small amount of nuclear material or do not conduct activities for peaceful use of nuclear energy.

50 IAEA, “Safeguards Statement for 2022,” 2023.

51 The ABACC stated at the NPT PrepCom, “Throughout these 32 years, ABACC has carried out more than 3,500 inspections at nuclear facilities in both countries, including more than 300 unannounced inspections. I would like to emphasize that despite all restrictions caused by the pandemic of COVID-19, ABACC was able to comply with its Annual Verification Plan, and performed 134 inspections in 2020 and 122 inspections in 2021.” “Statement of the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC),” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, July 31, 2023.

52 GC(66)/RES/11, September 2023.

53 Saudi Arabia is on the verge of completing its first research reactor. Prior to importing nuclear fuel, the country needs to renegotiate its safeguards agreement. This involves transitioning from the safeguards activities stipulated under the SQP to those required by a comprehensive safeguards agreement. Additionally, it is essential for Saudi Arabia to enter into a subsidiary arrangement with the IAEA to ensure all nuclear materials and activities are adequately safeguarded. The current SQP in Saudi Arabia does not permit verification during the reactor design and construction stage, known as Design Information Verification (DIV). Such verification is mandatory for new research reactors, like the one Saudi Arabia is currently developing.

54 “Statement of the Saudi Arabia,” IAEA General Conference, September 25, 2023.

55 Pesha Magid, “IAEA Chief Says Saudi Research Reactor Almost Complete,” Reuters, December 13, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/iaea-chief-says-saudi-research-reactor-almost-complete-202 3-12-13/.

56 IAEA, “Safeguards Statement for 2022.”

57 GOV/2023/41-GC(67)/20, August 25, 2023.

58 Ibid.

59 GOV/2023/57, November 15, 2023.

60 GOV/2023/24, May 31, 2023.

61 “IAEA Director General’s Statement on Verification in Iran,” September 16, 2023, https://www. iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/iaea-director-generals-statement-on-verification-in-iran-0.

62 “EU Urges Iran to Reconsider Barring of UN Nuclear Watchdog Inspectors,” France 24, February 17, 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20230917-eu-urges-iran-to-reconsider-barring-un-nuc lear-watchdog-inspectors.

63 Parisa Hafezi and Michelle Nichols, “President Raisi Says Iran Has ‘No Problem’ with IAEA Inspections,” Reuters, September 21, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/president-raisi-says-iran-has-no-problem-with-iaea-inspections-2023-09-21/.

64 “Statement by Iran,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

65 GOV/2021/15, February 23, 2021.

66 IAEA, “Safeguards Statement for 2022.”

67 Jon Gambrell, “Iran Gives ‘Detailed Answers’ to UN Inspectors 0ver 2 Sites Where Manmade Uranium Particles Found,” AP News, July 26, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/iran-nuclear-program-iaea-answers-uranium-49d750f406b9321b266f9641b00fed75.

68 Participating countries include Australia, Austria, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

69 “International Joint Statement at IAEA Board of Governors on NPT Safeguards Agreement with Iran,” September 14, 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/international-joint-statement-at-iaea-board-of-governors-on-npt-safeguards-agreement-with-iran.

70 IAEA, “Safeguards Statement for 2022.”

71 Ibid.

72 “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” March 13, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/ statements-releases/2023/03/13/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-2/.

73 GOV/INF/2023/10, May 31, 2023.

74 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.31, August 2, 2023.

75 “Statement by Russia,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

76 “Statement by Indonesia,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

77 “Statement of Egypt,” Cluster 2, First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 4, 2023.

78 See, for instance, Richard Marles, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister for Defence, “AUKUS Nuclear-Powered Submarine Pathway,” March 14, 2023, https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/ 2023-03-14/aukus-nuclear-powered-submarine-pathway.

79 “Statement by Australia,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

80 NPT/CONF.2020/WP.66, July 22, 2022.

81 “Statement by Brazil,” First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon, August 1, 2023.

82 “Statement by the United States,” IAEA Board of Governors, June 9, 2021, https://vienna.usmi ssion.gov/iaea-bog-2020-safeguards-implementation-report/; “Statement by the EU,” IAEA Board of Governors, June 7-11, 2021.

83 IAEA, “Safeguards Statement for 2022.”

84 GC(67)/RES/16, September 30, 2023.