Hiroshima Report 2024(3) Efforts to Maintain and Improve the Highest Level of Nuclear Security

A) Minimization of HEU and separated plutonium stockpile in civilian use

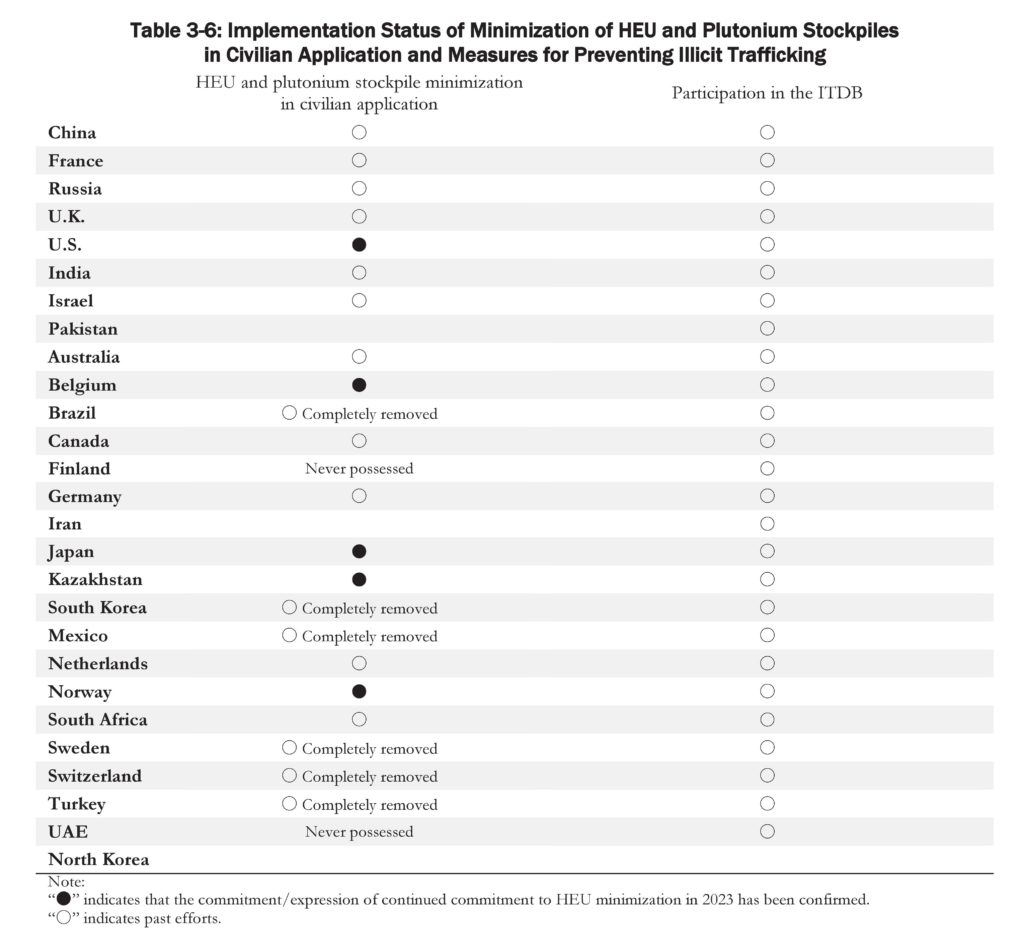

Today, minimizing HEU and separated plutonium inventory is one of the key indicators for achieving the highest level of nuclear security.119 As a result of the 2004 GTRI as well as through a series of efforts through the Nuclear Security Summit process since 2010 to minimize the use of HEU and plutonium, South America, Central Europe, and Southeast Asia have become areas where there are no high-risk nuclear materials at present.120

HEU

➢ China121: Will “continue to participate in the cooperation on conversion of HEU to low enriched uranium (LEU) for micro-reactors and to support countries in minimising the use of HEU.”

➢ Kazakhstan122: Has “successfully completed the power startup of the water-cooled IVG.1M reactor low-enriched fuel” in May. With this, two out of three Kazakhstan’s nuclear reactors have already been converted to LEU fuel. For the remaining pulsed graphite nuclear reactor, analysis and other work is underway to convert the reactor to low-enriched uranium fuel.

➢ Japan123: “Japan decided to remove HEU fuel from the Kinki University Teaching and Research Reactor (UTR-KINKI), which is the last research reactor possessing HEU in Japan, and convert it to an LEU reactor last September and started preparing for implementing this decision.”

➢ Norway124: The Institute for Energy Technology is collaborating with the NNSA and Savannah River National Laboratory in the United States on a project to eliminate all HEU in Norway by diluting it to LEU. Dilution is expected to begin in 2024, and when the project is completed in the next few years, Norway will be HEU-free.

The United States announced a policy to improve nuclear material security and prevent any act of nuclear terrorism, including following points.125

➢ “Minimize the production and retention of weapons-usable nuclear materials to only those quantities required to support vital national security interests;

➢ Refrain from the use of weapons-usable nuclear material in new civil reactors or for other civil purposes unless that use supports vital U.S. national interests;

➢ Focus civil nuclear research and development on approaches that avoid producing and accumulating weapons-usable nuclear material and enable viable technologies to replace current civil uses of these materials;

➢ Dispose of nuclear material that is in excess to national security or civil needs in a safe and secure manner.”

The EU encouraged all states to minimize HEU in civilian stocks and use, where technically and economically feasible, and to share experiences including updates on progress in this regard.126

In addition, Kazakhstan and the United States signed a joint statement on minimizing HEU stockpiling in Kazakhstan during the IAEA General Conference in September.127 In the statement, the two countries agreed to continue cooperation on the safe storage and eventual dilution of spent HEU fuel from the IVG.1M and to complete the dilution and immobilization of irradiated HEU fuel from the impulse graphite reactor (IGR) in 2027 and to develop a roadmap for identifying alternatives for the conversion of IGRs to LEU fuel.

On the other hand, in the United States, which has led international efforts to minimize HEU, the Idaho National Laboratory is planning to conduct a Molten Chloride Reactor Experiment (MCRE) as part of the Molten Chloride Fast Reactor (MCFR) project with a commercial partner. According to the draft environmental assessment, the MCRE will use more than 600 kilograms of weapon-grade HEU as fuel. Although MCFR is expected to use high-purity LEU, the experiment will use HEU as fuel. While MCFR is projected to use high-assay LEU, the experiment will use HEU as a cost-saving measure.128 This move has been criticized as going against efforts to minimize HEU.129

In addition to the efforts by the countries mentioned above to minimize HEU, Germany and the United Kingdom each voluntarily reported their civilian HEU inventories in their plutonium management reports (INFCIRC/549) for 2023 as well.130 On the other hand, no other countries in this survey made similar reports.

Such reporting is encouraged in the Joint Statement on Minimizing and Reducing Highly Enriched Uranium for Civilian Use (INFCIRC/912), issued in 2017, using the standardized form for voluntary reporting attached to this Joint Statement.131 The use of the standardized form allows for the sharing of information that is desired to be disclosed and, if submitted on a regular basis, allows the international community to evaluate the country’s efforts to minimize HEU.

Twenty-one countries are participating in the Joint Statement, including six countries surveyed for Hiroshima Report possessing HEU. Only two out of six countries (Australia and Norway) have so far submitted reports to the IAEA using this form. No country did so in 2023.132

G7-NPDG statement issued in April stated G7 countries affirmed their “commitment to minimise HEU stocks globally and encourage states with civil stocks of HEU to further reduce or eliminate them where economically and technically feasible.”133

Separated plutonium

While the Nuclear Security Resolution adopted at the 67th IAEA General Conference recognizes the importance of minimizing HEU use where technically and economically feasible, it does not mention minimizing separated plutonium. The communiqué of the 2014 Hague Nuclear Security Summit, however, encourages states to keep their stockpile “to the minimum level, as consistent with national requirements.”134

In this regard, in February, Japan announced its latest Plutonium Utilization Plan. In response to this plan, on February 28, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) announced their views on the validity of the Plutonium Utilization Plan for FY2023, which was issued by the Federation of Electric Power Companies and stated that the amount of plutonium held in FY2023 is expected to be about 44.5 tons, since no new plutonium will be recovered and about 0.7 tons of plutonium will be consumed. With this, the AEC expressed its views on the validity of the Plutonium Utilization Plan for FY2023 is appropriate at this moment, taking into account the operation plan of the plutonium thermal reactors in FY2023, the outlook for the operation of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant and other facilities, as well as the status of efforts to process Mixed Oxide (MOX) fuel from the plutonium held overseas.135

In Japan, the amount of plutonium held has been gradually decreasing each year since the AEC decided in July 2018 to reduce its holdings and to ensure that such holdings do not exceed the level as of 2018.136 According to the NTI, no other country has pledged to cap its inventory of separated plutonium like Japan.137 On the other hand, Japan’s inventory remains by far the largest, accounting for almost 99% of all non-nuclear-weapon States’ stockpiles.

B) Prevention of illicit trafficking

Nuclear detection, nuclear forensics, research and development of new technologies to strengthen capacity of law enforcement and customs, as well as participation in the IAEA’s Incident and Trafficking Database (ITDB) have all been regarded as important measures for preventing illicit trafficking of nuclear materials. The ITDB is a database on incidents related to unauthorized possession, illicit trafficking, illegal dispersal of radioactive material, as well as discovery of nuclear and other radioactive material out of regulatory control. It has been attracting attention as it provides useful statistics which enable us to realize the real threat of nuclear terrorism.

Myanmar newly joined the ITDB, bringing the total number of participating countries to 143 as of the end of 2022 (see Table 3-6 for participation status of countries surveyed).138 From the start of the ITDB in 1993 to the end of December 2022, 4,075 cases were reported in total. In 2022, 146 incidents were reported in total by 31 countries, which is an increase of 26 incidents from 2021. The IAEA points out that “these indicate that unauthorized activities and events involving nuclear and other radioactive material, including incidents of trafficking and malicious use, continue to follow historical averages.”139

The ITDB categorizes the types of incidents to three groups. Group I: incidents that are, or are likely to be, connected with trafficking or malicious use; Group II: incidents of undetermined intent, and Group III: incidents that are not, or are unlikely to be, connected with trafficking or malicious use.

Of the 4,075 confirmed incidents, there are 344 within Group I, 1,036 incidents within Group II and 2,695 incidents within Group III. Of these, 14% of all cases involved nuclear material,140 59% involved other radioactive material and 27% involved radioactive contamination or other material. It is estimated that about 52% of all theft incidents since 1993 have occurred during authorized transport. Over the past decade, the proportion has been about 62%, which the IAEA says highlights the importance of strengthening measures to protect radioactive materials during transport. The majority of materials reported to the ITDB as stolen or lost (or otherwise missing under uncertain circumstances), involve radioactive sources that are used in industrial, material analysis or medical applications.141

The trafficking or intent of malicious use around 88% of thefts remains undetermined. On the other hand, 3.5% of the reported thefts have been confirmed to be related to trafficking.

The ITDB does not disclose details of reported cases or illicit trafficking in order to protect sensitive information in participating countries.

In connection with the illicit trafficking of nuclear and other radioactive materials, countries are working to develop national nuclear security detection architectures, and the IAEA has been assisting them through the development of roadmaps for their design and implementation. Five new countries in the African region drafted roadmaps for 2022, bringing the total number of countries using roadmaps to 36.142

Ensuring nuclear security at large public events in each country has also become important, and in May 2023, a national workshop on the Development and Implementation of Nuclear Security Systems and Measures for Major Public Events was held in Dubai, UAE.143

C) Acceptance of international nuclear security review missions

The IAEA’s international assessment missions, in which international experts provide advice on the implementation of international instruments and IAEA guidance on the protection of nuclear and other radioactive material and related facilities and activities, include the IPPAS, the International Nuclear Security Advisory Service (INSServ) and missions to develop Integrated Nuclear Security Support Programmes (INSSP).144 In addition, a new advisory mission, the Regulatory Infrastructure Mission for Radiation Safety and Nuclear Security (RISS), was launched in March 2022.145

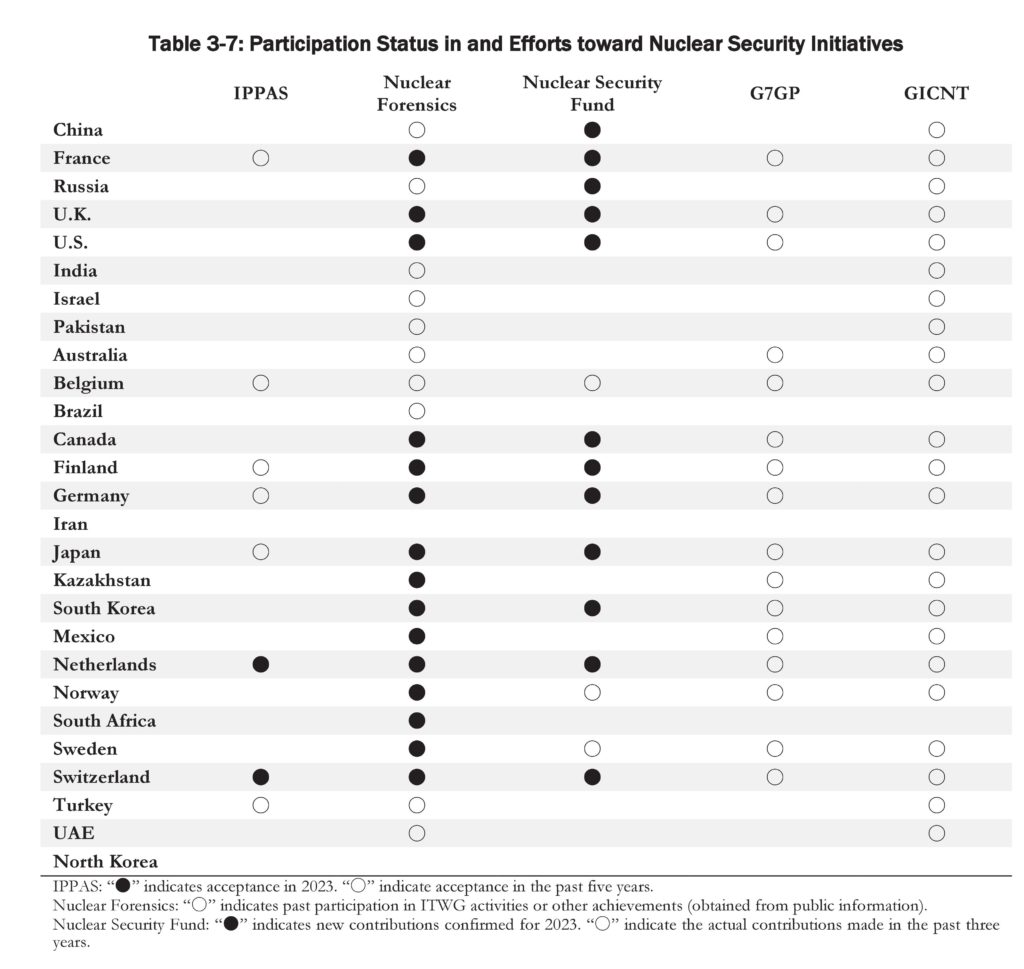

For the IPPAS missions, which are particularly high-profile, a total of five countries have hosted them in 2023: Nigeria, Kuwait, and Zambia,146 plus two of the countries covered by this survey, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The mission to Zambia in September brought the total number of IPPAS missions to 100 since its inception in 1996. For the first three countries, it was the first time for them to receive the mission. It indicates that there has been an expansion of mission acceptance to countries in the “Global South.”

As for the Netherlands, this was their fifth time to host the mission, following the previous one in 2012. In addition to the country’s overall nuclear security regime, including computer security, the implementation of the CPPNM and A/CPPNM was also reviewed.147

Switzerland hosted the mission as a follow-up to the one in 2018 and all five modules were reviewed for the first time for them.148 The mission team commented that “the inclusion of one additional module on the security of radioactive material underscores Switzerland’s integrated approach towards physical protection.”149

Regarding future missions, Japan, which decided in December 2022 to accept their second IPPAS mission, announced the status of their preparations in April 2023. According to the announcement, they plan to receive a mission in mid-2024 (June/July).150

While there has been a noticeable trend toward active acceptance of IPPAS missions and follow-up missions in the Western countries covered by this survey, there are a certain number of countries that have never accepted a mission, indicating a bifurcation of the situation (see Table 3-7).

It once became trend to make an IPPAS mission report available to the public while protecting sensitive information, from the perspective of transparency and accountability regarding the status of nuclear security implementation in countries. To date, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia, Canada and Japan released part of their reports (see Table 3- 6).151 However, no similar developments have been seen since 2020.

INSServ is a mission initiated in 2006 to review national nuclear security regimes for radioactive materials out of regulatory control. In 2023, Viet Nam and Georgia hosted this mission.152 A total of 85 missions have been carried out to date.

D) Technology development – nuclear forensics

Nuclear forensics is an important technology for nuclear security in that it can identify and prosecute perpetrators of illicit trafficking and malicious acts involving nuclear and radiological materials. Efforts and support for further advancement of this technology, the establishment of national systems as well as international networking systems have been made to date. Capacity building in the areas of radiological crime scene management and nuclear forensics continues to be important for countries. The Nuclear Security Resolution adopted by the IAEA General Conference in September 2023 encouraged countries that have not yet done so “to consider establishing, where practical, national nuclear forensics libraries”153 (para. 55).154 In July, an IAEA Technical Document entitled “Establishing a Nuclear Forensics Capability: Application of Analytical Techniques” was published.155

On nuclear forensics, Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and the Atomic Energy Authority of Thailand, hosted a joint workshop on nuclear security and safeguards in Bangkok in January, with a tabletop exercise on nuclear forensics as a special event of the workshop. Thirty-eight participants from 12 countries (including the five countries surveyed in this survey: Australia, China, Kazakhstan, Japan and South Korea) took part in the exercise.156 The United States hosted an IAEA international training course on nuclear forensics methodology in March.157

At the First PrepCom for the 11th NPT RevCon held in July, Australia, on behalf of 19 countries (the countries covered by this survey: Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States), submitted a working paper entitled “Nuclear Forensic Science for Nuclear Security.”158 The working paper encourages states:

➢ “To develop and enhance nuclear forensic capabilities and utilize, as appropriate, the support of IAEA and the Nuclear Forensics International Technical Working Group in areas such as enhancing nuclear forensic capabilities and providing relevant training assistance to States;

➢ To evaluate and adapt existing national response frameworks to incorporate the effective use of nuclear forensic capabilities;

➢ Cooperation within regions to identify areas of focus for future regional training activities in relation to nuclear forensics, with a view to enhancing training effectiveness and to ensuring that the provision of training matches the needs of States within the region.”

An important multilateral cooperation effort on nuclear forensics technology is the International Technical Working Group on Nuclear Forensics (ITWG), which was established in 1995. To date, more than 50 countries have participated in its annual meetings.159

In June 2023, the ITWG held its 26th annual meeting in Tbilisi, Georgia, with approximately 80 participants.160 The countries covered by this survey, including Australia, Canada, Germany, Kazakhstan, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States, participated in the meeting. At the meeting, the IAEA, Interpol, and the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT)161 reported on their latest activities, and the main results of the seventh exercise of the Cooperative Material Comparison Exercise (CMX),162 one of the ITWG’s main activities, were presented.163 Several task groups under the ITWG have been active, including the Library Task Group, which reviewed the latest implementation of the Galaxy Serpent Exercise, a web-based international desktop exercise to build a national nuclear forensics library. The most recent, Exercise 5 (GSv5), involved 30 teams comprised of about 180 people.164

According to the ITWG newsletters which featured South Africa’s efforts to establish nuclear forensics capabilities, it has established an advanced nuclear forensics laboratory over the past decade in cooperation with the United States.165 It developed analytical methods for forensic fingerprinting of uranium ore concentrates and radioactive materials and established a prototype for a national nuclear forensics lab.

E) Human resource development and capacity building and support activities

It is an essential responsibility of a state to build the capacity of organizations and people to establish, implement and sustain a nuclear security regime.166 The IAEA plays an important role in providing coordinated education and training programs that strengthen capabilities in states to address and sustain nuclear security.167

On October 3, 2023, the IAEA’s Nuclear Security Training and Demonstration Center (NSTDC), “the first international facility of its type, to support the growing efforts to tackle nuclear terrorism,” opened in Seibersdorf, on the outskirts of Vienna. According to the IAEA, NSTDC “will provide more than 2,000 square meters of specialized technical infrastructure and equipment for course participants to learn about the physical protection of nuclear and other radioactive material, as well as detection and response to criminal acts involving nuclear material and facilities.”168

The NSTDC provides for advanced training in areas such as physical protection of nuclear and other radioactive material and facilities; detection of and response to criminal and intentional unauthorized acts; computer and information security; nuclear forensics; preparation for major public events implementing nuclear security measures; transport nuclear security.169

Elena Buglova, Director of the IAEA Nuclear Security Division said, “By building this new centre, the IAEA can offer unique training activities to address existing gaps using specialized up-to-date equipment, computer-based simulation tools and advanced training methods.”170

Belgium, Canada, Denmark, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States contributed €14 million in total to the construction and development of the NSTDC.171

In the area of nuclear security education, the IAEA held the International School of Nuclear Security in the Vienna in August 2023. This was attended by 56 female fellows from 46 countries from the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellowship Program (MSCFP), which was established by the IAEA in 2020.172

International network for training and support

The IAEA’s activities on training for human resource development and capacity building are carried out in close cooperation with states, including the activities of National Nuclear Security Support Centres (NSSCs) and the International Network of NSSCs (NSSC Network).

The International Network of NSSCs, established by the IAEA in 2012, plays an important role as a keystone for collaboration and networking among national NSSCs.173 75 institutions from 68 countries and 10 observers are participating in the NSSC network. Countries participating in the NSSC network in the countries surveyed for the Hiroshima Report include Brazil, Canada, China, France, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Pakistan, Russia and the United States.174 To date, the following six regional and sub-regional groups have been established: the Africa regional group; the Arab States in Asia group; the Asia Regional Network; the Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine Consortium; the Latin America; and Southeast Asian Nations regional group.175

In February 2023, an annual meeting of NSSC Network took place in Thailand with more than 70 participants from 42 states and two observer organizations. “The aim of the event was to bring together IAEA Member States that have established or are planning to establish an NSSC, in order to facilitate information and resources sharing on key technical themes relevant to developing and operating an NSSC as well as to work individually and collaboratively among the NSSC Network Working Groups to plan activities and discuss priorities for the upcoming year.”176

As for efforts for human resources development by the countries covered by this survey, China hosted the IAEA Regional Workshop and Technical Exchange on Human Resource Development for NSSCs in the Asia and the Pacific Region at State Nuclear Security Technology Center from October 30 to November 3.177 In October, the JAEA/ISCN organized the Regional Training Course on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and Nuclear Facilities in Japan.178 On human resource development, the United States stated at the March IAEA Board of Governors meeting that, “developing states’ human resources is necessary to prevent nuclear terrorism and strengthen nuclear security,” and that “diverse teams and workforces are not only important in achieving the fifth UN Sustainable Development Goals (achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls) but are essential if we are to have the necessary talent and resources to tackle complex nuclear security challenges before us.”179 (phase in parentheses added by the citer)

International network for education

The International Nuclear Security Education Network (INSEN) was established in 2010 to promote sustainable nuclear security education through a partnership between the IAEA and educational and research institutions as well as other stakeholders.180

As of August 2023, the INSEN had 204 members and 13 observers from a total of 72 countries.181 According to the IAEA’s Nuclear Security Review 2023, membership in INSEN increased by 11 institutions from nine states and three observer institutions in 2022.182 Among the countries covered by this survey, institutions from Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Russia, South Africa, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States participated.

In recent years, “there was an increase in the number of INSEN members offering new degree programmes in nuclear security. There was also an increase in the number of members teaching courses or modules in existing programmes.”183

As for its activity in 2023, Leadership Meeting was held in Vienna in February. “At the meeting, participants evaluated the progress of the action plan for the current year, discussed nuclear security working group activities, and prepared for the annual meeting.”184

F) Nuclear security plan and nuclear security fund

The IAEA developed a comprehensive action plan, called the Nuclear Security Plan, for protection against nuclear terrorism, which was approved by the Board of Governors in March 2002, marking its first-ever initiative in this regard. To facilitate the implementation of this plan, the Nuclear Security Fund (NSF) was established in the same year. Since then, IAEA Member States have been requested to contribute funds on a voluntary basis. Subsequent “Nuclear Security Plans” have been developed every four years since 2005, and activities in 2023 were carried out based on the sixth plan adopted in 2021,185 covering the period from 2022 to 2025.

The NSF is sustained through voluntary contributions from IAEA Member States and others. In paragraph 12 of the IAEA Nuclear Security Resolution adopted in 2023, it calls upon all IAEA Member States “to consider providing the necessary political, technical, and financial support, as appropriate, to the Agency’s efforts to enhance nuclear security through various arrangements at the bilateral, regional, and international levels.”186

According to the IAEA Nuclear Security Review 2023, in 2022, contributions or pledges to the NSF were made by 15 countries, including 12 countries subject to this survey (Canada, China, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Russia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States).187 The total revenue for the NSF in 2022 amounted to €29 million, approximately €5 million less than the previous year, marking the lowest amount in recent years. 188 The NSTDC, inaugurated in October 2023, incurred construction costs exceeding €18 million, covered by contributions from 15 donors.189

According to the IAEA, it still requires a significant amount of funding in order to implement a number of activities that have been identified as Member State priorities.190 The reason is because the IAEA “is unable to fund any of these activities with existing contributions due to the conditions placed by donors on the large majority of funds contributed to the NSF.”

On NSF, in its statement issued in April 2023, the G7-NPDG encouraged all IAEA Member States, “who are able to do so, to make financial and/or technical contributions to enable the IAEA to continue its work in this area, in particular to assist new comer countries to access nuclear technologies while observing the highest standards of nuclear safety, security and non-proliferation.”191

G) Participation in international efforts

International efforts to raise the level of nuclear security today form a multilayered structure. Major efforts by the international community in nuclear security include support for implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004) and multilateral forums such as the IAEA ICONS and the Nuclear Security Summit Process, which ended in 2016. Also, there are efforts by the G7 and the GICNT as a framework for multilateral cooperation on nuclear security.

UN Security Council Resolution 1540

With regard to Security Council Resolution 1540, it decided that states should take effective measures to establish and strengthen national control systems to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and their means of delivery, and calls for the development and maintenance of appropriate and effective measures of physical protection for that purpose.192 States are requested to submit reports to the United Nations on the obligations called for in this resolution. The submission of such reports will increase transparency regarding the nuclear security measures taken by states and contribute to international assurance regarding the implementation of such measures. See Table 3-6 for the status of submission of this report by the countries covered by this survey.

In 2023, two of the surveyed countries, India and Turkey, submitted the latest information to the United Nations. Regarding India, the recent activities of the Center of Excellence (COE) for the Global Centre for Nuclear Energy Partnership, which was established based on the commitment made by the Prime Minister at the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit to promote education on nuclear safety and security, were reported.193 Turkey provided updated information on achievements such as hosting the IPPAS mission in 2021 and the enactment of the Nuclear Regulation Law in March 2022.194

IAEA International Conference on Nuclear Security (ICONS)195

For ICONS, the fourth conference entitled “ICONS2024: Creating the Future” is scheduled to take place in May 2024, and the first Programme Committee Meeting was held in Vienna in March 2023 as part of the preparations for the conference.196 At the Board of Governors meeting in November, IAEA Director General urged “all Member States to participate at the highest level possible.”197 Regarding ICONS2024, Australia said that it “will provide an opportunity to share information and discuss best practices for ensuring nuclear security in the face of emerging threats” and it expects “the active engagement of all Members States in ICONS2024, and to an ambitious Ministerial Declaration that will inform the Agency’s future nuclear security activities.”198 The United States stated that ICONS2024 “is an important opportunity to collectively assess the current nuclear security landscape and collaborate to forge a better future” and urged “Member States to send ministerial-level participation and bring concrete deliverables and action plans.”199

Also, in the G7-NPDG statement issued in April, it stated that the G7 countries remain committed to contributing to the success of the ICONS2024 and it “will be a significant opportunity to raise awareness and strengthen nuclear security globally.”200

Furthermore, the Nuclear Safety and Security Group (NSSG) which was established under the G7 Global Partnership against Proliferation of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction (G7GP) published a report of activities for 2023 in December.201 The report mentioned regarding ICONS that each NSSG member stats shared their priorities for the Conference and discussed promoting universalization of A/CPPNM and the ICSANT, transportation security, new technologies, cyber security, Ukraine, and new types of reactors such as small modular reactors (SMRs). It also said that the NSSG recognizes “the importance of a successful outcome to the Conference, given the increase in the number of nuclear facilities being built, the development and expansion of nuclear science and technology for peaceful applications, and evolving advancements in technology requires more focus on strengthening the nuclear security framework to address contemporary challenges.”

Nuclear Security Summit Process202

The Nuclear Security Summit Process ended in 2016, but efforts have continued after the process ended through the Nuclear Security Contact Group (NSCG), which was established based on the Joint Statement on Sustained Action to Strengthen Global Nuclear Security. However, no public information on new participating countries or specific activities in recent years could be found.

As for the “Basket Initiative,”203 which launched at the Nuclear Security Summit Process, in which volunteer states promote initiatives through joint statements on specific themes, efforts are underway regarding the “Insider Threat Mitigation (INFCIRC/908)” led by the United States. For example, the “Insider Threat Newsletter” was published in 2023. It reviews the initiatives taken in 2022 and describes future initiatives, including plans for an international symposium on insider threats to be held in Belgium in March 2024.204 After being invited to participate in ICONS and other events, Switzerland and Slovenia joined INFCIRC/908 in 2020, but no new countries have been confirmed to participate since then. At the IAEA Board of Governors meeting in March 2023, Norway stated that endorsing these joint statements is a concrete step by Member States to demonstrate their commitment to improve their nuclear security efforts.205

GICNT206

The GICNT is an important multinational initiative for enhancing global capabilities in nuclear security, involving 89 countries, including numerous developing nations, as well as international organizations such as the IAEA, Interpol, and the United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT). The initiative actively engaged in practical activities such as training and workshops, and the development of practical guidelines. All countries under this survey except Iran, South Africa, and North Korea have participated in the GICNT. The organization appears to have temporarily suspended its activities in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and no information is available beyond its participation in the aforementioned ITWG annual meeting.

G7

The G7’s initiatives related to nuclear security include the G7GP,207 the NPDG, the NSSG, and the Nuclear and Radiological Working Group (NRSWG). In 2023, Japan held the G7 Presidency. The following is a summary of their respective activities in 2023.

The NPDG issued a statement at its meeting in April and stated that the threat of nuclear terrorism remains a grave and constant concern, expressing its position on pressing challenges.208 While the specific details have been described in various major sections of this report, some other key points include: for example, those G7 countries “strongly encourage the consideration of safety, security, and safeguards in nascent phases of reactor and facility design so that the next generation of peaceful nuclear technology contributes to reducing nuclear risks.”209

The GP Working Group met in Nagasaki in November, with approximately 140 participants from 15 Member States, the EU and other international organizations. Discussions were held on the prevention of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, as well as the exchange of views on specific initiatives for this purpose.210

As mentioned above, the NSSG published its report of activities for 2023 in December and in relation to nuclear security, mentioned about ICONS.211

The NRSWG held a meeting in Tokyo in March, with the participation of 21 countries. Discussions covered the latest information on nuclear security situation in Ukraine, the universality of the A/CPPNM, and issues related to human resource development.212

119 Regarding separated plutonium, it was mentioned for the first time in the series of Nuclear Security Summits the need to maintain them at the minimum level in the communique of the 2014 Hague Summit. The Ministerial Declaration of ICONS 2020 called upon “all Member States possessing HEU and separated plutonium in any application, … to make sure they are appropriately secured and accounted for, by and in the relevant State,” and encouraged “Member States, on a voluntary basis, to further minimize HEU in civilian stocks, when technically and economically feasible.” “Ministerial Declaration,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, February 10, 2020, p. 1.

120 “Secretary Moniz Remarks on Nuclear Security at IAEA Conference,” U.S. Department of Energy, December 5, 2016, https://www.energy.gov/articles/secretary-moniz-remarks-nuclear-security-iaea-con ference.

121 Ray Acheson and Laura Varella, “Report on Cluster Three,” NPT News in Review, Reaching Critical Will, Vol. 18, No. 5, August 9, 2023, p. 12.

122 “Statement by Kazakhstan,” at the 67th IAEA General Conference, September 25, 2023.

123 “Statement by Japan,” at the 67th IAEA General Conference, September 25, 2023.

124 “NNSA Administrator Visits Norway, A Key Ally, To Discuss Mutual Goals and Review Progress on an Innovative Nonproliferation Effort,” NNSA, April 6, 2023, https://www.energy.gov/nnsa/articles/ nnsa-administrator-visits-norway-key-ally-discuss-mutual-goals-and-review-progress.

125 “FACT SHEET: President Biden Signs National Security Memorandum to Counter Weapons of Mass Destruction Terrorism and Advance Nuclear and Radioactive Material Security,” The White House, March 2, 2023.

126 Ray Acheson and Laura Varella, “Report on Cluster Three,” NPT News in Review, Reaching Critical Will, Vol. 18, No. 5, August 9, 2023, p. 12.

127 “Joint Statement between the NNSA of the U.S. Department of Energy and the Ministry of Energy of the Republic of Kazakhstan,” National Nuclear Center, September 26, 2023, https://www.nnc.kz/en/ news/show/464.

128 “US Reactor Experiment to Use HEU,” IPFM Blog, May 21, 2023, https://fissilematerials.org/ blog/2023/05/us_reactor_experiment_to_.html; “US Government Urged to Stop The HEU Test Reactor Project,” IPFM Blog, May 30, 2023, https://fissilematerials.org/blog/2023/05/us_government _urged_to_st.html.

129 “Proposed MCRE Reactor Violates U.S. Nonproliferation Policy of HEU Minimization,” Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, May 30, 2023, https://npolicy.org/proposed-mcre-reactor-violates-u-s-nonproliferation-policy-of-heu-minimization/; Alan J. Kuperman, “U.S. Plan to Put Weapons-Grade Uranium in a Civilian Reactor Is Dangerous and Unnecessary,” Scientific American, October 20, 2023, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/u-s-plan-to-put-weapons-grade-uranium-in-a-civilian-reactor-is-dangerous-and-unnecessary/.

130 INFCIRC/549/Add.2-26, August 31, 2023; INFCIRC/549/Add.8/26, November 16, 2023.

131 “Joint Statement on Minimising and Eliminating the Use of Highly Enriched Uranium in Civilian Applications,” INFCIRC/912, February 16, 2020; “Australia’s 2019 INFCIRC/912 HEU Report,” IPFM Blog, January 23, 2020, http:// fissilematerials.org/blog/2020/01/australias_2019_infcirc91.html.

132 INFCIRC/912/Add.4, March 5, 2020 (Australia); INFCIRC/912/Add.3, August 19, 2019 (Norway). France, Germany, and the United Kingdom voluntarily added HEU inventory to their reporting of civilian separated plutonium inventory quantities under the International Plutonium Management Guidelines (INFCIRC/549).

133 “Statement of the G7 Non-Proliferation Directors Group.”

134 “The Hague Nuclear Security Summit Communiqué,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, March 25, 2014, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23823/141885.pdf.

135 Japan Atomic Energy Commission, “Plutonium Utilization Plans Published by the Federation of Electric Utilities and others (Opinion),” February 28, 2023, http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/sitemap /pdf/230228_kenkai.pdf.

136 Japan Atomic Energy Commission, “The Basic Principles on Japan’s Utilization of Plutonium,” July 31, 2018, http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/iinkai/teirei/3-3set.pdf.

137 Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), The 2023 NTI Nuclear Security Index, July 2023, p. 36.

138 IAEA, “IAEA Incident and Trafficking Database (ITDB) 2023 Factsheet,” https://www.iaea.org/ sites/default/files/22/01/itdb-factsheet.pdf.

139 Ibid.

140 These included 12 cases of HEU, three cases of plutonium and five cases of plutonium-beryllium neutron sources.

141 IAEA points out that “Devices containing radioactive sources can be attractive to a potential thief as they may be perceived to have a high resale or scrap metal value.”

142 IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, August 2023, p. 27.

143 Ibid, p. 19.

144 An international team of experts from Member States and IAEA reviews the nuclear security situation as implemented by mission host states, against the international guidelines and good practices contained in the 2005 A/CPPNM and IAEA Nuclear Security Series documents. The review will cover all aspects, from the regulatory framework to transport, information and computer security arrangements.

145 IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, p. 9.

146 “IAEA Concludes International Physical Protection Advisory Mission in Nigeria,” IAEA News, July 14, 2023; “IAEA Completes International Physical Protection Advisory Service Mission in Kuwait,” IAEA News, June 8, 2023; “IAEA Concludes International Physical Protection Advisory Service Mission in Zambia,” IAEA News, September 8, 2023.

147 “IAEA Concludes International Physical Protection Advisory Service Mission in the Netherlands,” IAEA News, October 16, 2023.

148 The five modules are: nuclear security regimes; nuclear facilities; transport; information and computer security; nuclear security of radioactive materials; and associated facilities and activities. “IAEA Concludes International Physical Protection Advisory Follow-Up Mission in Switzerland,” IAEA News, November 10, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/iaea-concludes-international-physical-protec tion-advisory-follow-up-mission-in-switzerland.

149 Ibid.

150 “Statement by Japan,” at the 67th IAEA General Conference, September 25, 2023; Nuclear Regulation Authority, “Status on the Preparation for Receiving an IAEA IPPAS Mission,” April 12, 2023, https://www.nra.go.jp/data/000426587.pdf.

151 “Report of the Netherlands,” February 2012, https://www.autoriteitnvs.nl/binaries/anvs/docu menten/rapporten/2014/12/24/ippas/international-physical-protection-advisery-service-ippas-v2.pdf; “Report of Sweden,” October 2016, https://www.stralsakerhetsmyndigheten.se/conten assets/ 27a6dd9e94e54dc189cecfa7c7f2f910/draft-follow-up-mission-report-sweden.pdf; “Report of Australia,” November 2017, https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-ippas-follow-up-mission-report.pdf; “Report of Canada,” October 2015, http://www.nuclearsafety.gc.ca/eng/pdfs/IPPAS/ Canadas-IPPAS-Mission-Report-2015-eng.pdf; “Report of Japan,” February 2015, https://www.nra.go.jp/data/0002955 52.pdf.

152 IAEA, Nuclear Security Report 2023, p. 20.

153 “A National Nuclear Forensics Library is a national system for the identification of nuclear and other radioactive materials found out of regulatory control. A Library enables comparisons to information on known materials and data obtained from analytical measurements of nuclear or other radioactive materials found out of regulatory control.” IAEA, “Development of a National Nuclear Forensics Library: A System for the Identification of Nuclear or Other Radioactive Material out of Regulatory Control,” IAEA-TDL-009, 2018, p. 1.

154 IAEA, “Nuclear Security Resolution,” September 2023, p. 10. Whether to build a national nuclear forensics library is a matter of national sovereignty, and according to the ISCN, the number of countries that are building such libraries is quite small by global standards. “How Far Has the Nuclear Forensics Library Establishment Progressed? (in Japanese),” ISCN, December 2021, https://www.jaea.go.jp/ 04/iscn/activity/2021-12-15/2021-12-15-07.pdf.

155 IAEA, “Establishing a Nuclear Forensic Capability: Application of Analytical Techniques,” 2023, https://www.iaea.org/publications/15286/establishing-a-nuclear-forensic-capability-application-of-analytical-techniques.

156 “Report of FNCA 2022 Workshop on Nuclear Security and Safeguards Project January 10-12, 2023, Bangkok, Thailand,” Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia, https://www.fnca.mext.go.jp/English /nss/e_ws_2022.html.

157 IAEA, Nuclear Security Report 2023, p. 18.

158 NPT/CONF.2026/PC.I/WP.7/Rev.1, August 10, 2023.

159 ITWG, “Nuclear Forensics Update,” No. 24, September 2022, p. 2.

160 Michael Curry and Maria Wallenius, “Co-Chairs’ Summary of the ITWG-26 Annual Meeting,” ITWG Nuclear Forensics Update, No. 28, September 2023, p. 1; “MOIA Hosted the 26th Annual Meeting of the Nuclear Forensics International Technical Working Group (ITWG),” U.S. Embassy Tbilisi, June 23, 2023.

161 Within the GICNT, a Nuclear Forensics Working Group (NFWG, chaired by Canada) has been established, which also conducts a number of workshops and desk exercises with a view to strengthening nuclear forensics capabilities through multilateral cooperation and works closely with the ITWG.

162 Although CMX had only six participating analytical laboratories at the start of the initiative, in recent years CMX has had more than 20 participating institutions.

163 Michael Curry and Maria Wallenius, “Co-Chairs’ Summary of the ITWG-26 Annual Meeting,” ITWG Nuclear Forensics Update, No. 28, September 2023, p. 1.

164 Ibid, p. 2.

165 Aubrey Newwamondo, Jeaneth Kabini, Banyana Kokwane and Rachel Lindvall, “Establishing A Nuclear Forensics Laboratory at NESCA in South Africa,” ITWG Nuclear Forensics Update, No. 27, June 2023, pp. 4-5.

166 IAEA, “Building Capacity for Nuclear Security Implementing Guide,” IAEA Nuclear Security Series, No. 31-3, 2018, p. 1.

167 IAEA, Nuclear Security Plan 2022-2025, GC(65)/24, September 15, 2021, p. 18.

168 “IAEA Training Centre for Nuclear Security Opens Doors to Build Expertise in Countering Nuclear Terrorism,” IAEA Press Release, October 3, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/pressreleases/iaea-training-centre-for-nuclear-security-opens-doors-to-build-expertise-in-countering-nuclear-terrorism; “Nuclear Security Training and Demonstration Centre,” IAEA, https://www.iaea.org/about/ organizational-structure/department-of-nuclear-safety-and-security/division-of-nuclear-security/iaea-nuclear-security-training-and-demonstration-centre.

169 “Nuclear Security Training and Demonstration Centre.”

170 “IAEA Training Centre for Nuclear Security Opens Doors to Build Expertise in Countering Nuclear Terrorism,” IAEA Press Release, October 3, 2023.

171 “IAEA Nuclear Security Training and Demonstration Centre Nears Completion,” IAEA, August 15, 2022, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/iaea-nuclear-security-training-and-demonstration-centre-nears-completion.

172 The MSCFP aims to support the next generation of women leaders in the nuclear field through scholarships, internships, and training and networking opportunities. In the last three years since 2020, a total of 169 MSCFP recipients from various educational backgrounds in the field of nuclear science and technology have participated in the school. IAEA, “Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellows Trained in Nuclear Security,” September 4, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/marie-sklodowska-curie-fellows-trained-in-nuclear-security.

173 For basic information on the NSSC network, see: IAEA, “Understanding Nuclear Security Support Centres (NSSCs) in FIVE QUESTIONS,” https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/20/08/nssc-five-questions.pdf.

174 IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, August 2023, p. 12, Appendix C, p. 1.

175 “The Chair’s Report on the 2023 Annual Meeting of the International Network for Nuclear Security Training and Support Centres (NSSC Network),” IAEA, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/ 23/06/chairs_report_annual_meeting_2023.pdf.

176 Ibid.

177 “Regional Workshop and Technical Exchange on Human Resource Development for Nuclear Security Support Centres in the Asia and the Pacific Region,” https://elesen.aelb.gov.my/ipakar/upload/ 20230721111938.23-02983E_Encl.pdf?p_kur_iklanDir=Asc&p_kur_iklanPageSize=5&id=1697.

178 “Statement by Japan,” at the 67th IAEA General Conference, September 25, 2023.

179 “U.S. Statement under Agenda Item 3,” at the IAEA BoG Meeting, March 6, 2023.

180 IAEA, “International Nuclear Security Education Network (INSEN),” https://www.iaea.org/ services/networks/insen. Their work includes the development of peer-reviewed teaching materials; faculty development in different areas of nuclear security; joint research activities; student exchange programmes; academic theses supervision and evaluation; knowledge management; promotion of nuclear security education; and other related activities.

181 Andrea Rahandini, “Nuclear Security Education: IAEA Partners with Universities and Research Institutions,” IAEA News, August 1, 2023, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/nuclear-security-education-iaea-partners-with-universities-and-research-institutions; IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, August 2023, p. 12.

182 IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, August 2023, p. 13.

183 Ibid, pp. 12-13.

184 Ibid, p. 10.

185 IAEA, Nuclear Security Plan 2022-2025: Report by the Director General, GC(65)/24, September 15, 2021.

186 IAEA, “Nuclear Security Resolution,” September 2023, p. 3, p. 5.

187 IAEA, Nuclear Security Review 2023, p. 31.

188 In 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, the revenue was €33 million, €38 million, €45 million, and €34 million, respectively.

189 “IAEA Training Centre for Nuclear Security Opens Doors to Build Expertise in Countering Nuclear Terrorism,” IAEA Press Release, October 3, 2023.

190 Ibid, pp. 32-33.

191 “Statement of the G7 Non-Proliferation Directors Group.”

192 UN Security Council, “Resolution 1540 (2004),” S/RES/1540 (2004), April 28, 2004.

193 “National Submission of India,” S/AC.44/2023/2, August 8, 2023, p. 7.

194 “National Submission of Türkiye,” February 8, 2023, https://www.un.org/en/sc/1540/documents/ TurkiyeReport8Feb2023.pdf.

195 ICONS has its origins in a ministerial-level meeting held in 2013 to maintain momentum for international efforts through the high-level political commitment brought about through the Nuclear Security Summit process. Subsequently, the second meeting took place in 2016, and it has been convened every four years since then. ICONS serves as a crucial platform, providing an opportunity for countries to announce their achievements and new commitments in the field of nuclear security. ICONS also allows countries to announce additional financial, human resources, and technical contributions to support these efforts.

196 IAEA, Nuclear Security Report 2023, p. 3.

197 “IAEA Director General’s Introductory Statement to the Board of Governors,” IAEA, November 22, 2023.

198 “Statement by Australia on Agenda Item 4,” at IAEA BoG Meeting, September 11, 2023, Australian Embassy and Permanent Mission in Austria, https://austria.embassy.gov.au/vien/IAEASeptBoard _4.html.

199 “Statement by the U.S.-Agenda Item 8,” at the IAEA B BoG Meeting, U.S. Mission in Vienna, November 2023, https://vienna.usmission.gov/u-s-statement-agenda-item-iaea-board-of-governors-meet ing-november-2023/.

200 “Statement of the G7 Non-Proliferation Directors Group.”

201 “Japanese G7 Presidency 2023 Report Nuclear Safety and Security Group (NSSG),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, December 1, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100593408.pdf.

202 Launched in 2010 at the initiative of US President Barack Obama, it has been held a total of four times by 2016 (2012 in South Korea, 2014 in the Netherlands and 2016 in the US).

203 Other initiatives include: Transportation Security (INFCIRC/909), in which Japan is the lead country; Minimizing and Eliminating the Use of HEU for Civilian Use (INFCIRC/912); and Nuclear Forensics (INFCIRC/917), in which Australia is the lead country. “What Are INFCIRCs?” Nuclear Threat Initiative, https://www.ntiindex.org/story/what-are-nuclear-security-infcircs/.

204 “Know Your Insiders,” Newsletter of the Advancing INFCIRC/908 “Mitigating Insider Threats” International Working Group, January 2023, http://insiderthreatmitigation.org/assets/docs/ 2022_IWG_Newsletter_20230131_PNNL-SA-181576.pdf.

205 “Statement by Norway on Nuclear Security Review 2023,” at the IAEA BoG Meeting, March 2023.

206 The initiative, jointly announced by Russia and the United States at the 2006 G8 St. Petersburg Summit, aims to counter the threat of nuclear terrorism through international efforts.

207 The initiative was agreed at the 2002 Kananaskis Summit (Canada) by the then G8, including Russia, with the main objective of preventing the proliferation of WMDs and related substances, etc. Currently, the G7 is leading the initiative, with 30 countries and the EU participating.

208 “Statement of the G7 Non-Proliferation Directors Group.”

209 Specific efforts are: 1) Incorporate the highest standards of safety, safeguards, and security by design; 2) Avoid unnecessary use and accumulation of weapons-usable nuclear materials; 3) Minimize opportunities for theft and diversion of nuclear material; and 4) Contain resilient safety mechanisms.

210 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Second Meeting of the Global Partnership Working Group (Summary of Results),” November 10, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press4e_00333 8.html.

211 “Japanese G7 Presidency 2023 Report Nuclear Safety and Security Group (NSSG),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, December 1, 2023, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100593408.pdf.

212 “Report on the Session of the Nuclear and Radiation Security Sub-Working Group (NRSWG) of the G7 Global Partnership,” ISCN Newsletter, No. 317, May 2023, pp. 52-53.

-150x150.jpg)