9 A City in Search of Peace

(1) Peace Administration Hiroshima City’s peace administration undertook the significant role of promoting a crucial part of the reconstruction process—the creation of a new identity for Hiroshima. Two years after the bombing, the Constitution of Japan was enforced on May 3, 1947. In Hiroshima, various actions were taken in support of the pacifism of the new constitution. On August 6, 1947, in response to the citizens’ requests, the first Peace Festival was held by the City and other organizations under the slogan of promoting a lasting peace.

Hiroshima City’s peace administration undertook the significant role of promoting a crucial part of the reconstruction process—the creation of a new identity for Hiroshima. Two years after the bombing, the Constitution of Japan was enforced on May 3, 1947. In Hiroshima, various actions were taken in support of the pacifism of the new constitution. On August 6, 1947, in response to the citizens’ requests, the first Peace Festival was held by the City and other organizations under the slogan of promoting a lasting peace.

In addition, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law (enforced on August 6, 1949) was the crystallization of Hiroshima citizens’ thoughts on the new constitution in a form of a law as the will of the people of Japan. At the start of the reconstruction of Hiroshima, there was a strong awareness of the pacifism inherent in the constitution among the citizens.

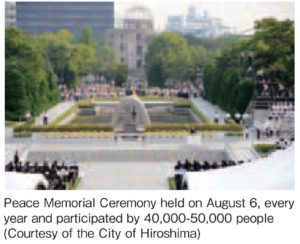

The Peace Festival has been held annually except for 1950. Today, it has been renamed the Peace Memorial Ceremony, and the Mayor of Hiroshima delivers the Peace Declaration during the ceremony which conveys Hiroshima’s wish for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the realization of lasting world peace.

(2) Peace Movements

The Peace Festival organized by Hiroshima City could be called the start of the peace movement, based on the experiences of the atomic bombing. The citizens’ call for world peace communicated from Hiroshima through means such as the Peace Declaration, and garnered great sympathy not only from within Japan but also from overseas. Various global actions for peace drew attention to the A-bombed cities, with the World Federalist Movement and the Partisans for Peace Movement coming to wield particularly powerful influence on local governments and citizens in Japan. The peace movements implemented by Hiroshima citizens gathered proponents of preserving the A-bomb Dome, elucidating the realities of the atomic bombing, and passing on survivor’s experiences of the bombing. The activities discovered a direction that leads to the activities of the NGO’s of today.

After the war, some were of the opinion that the A-bomb Dome should be preserved, while others were of the opinion that it should be torn down. Discussions were frequently held among citizens. However, as the urban area became reconstructed and the A-bombed structures gradually disappeared, the public support for preserving the A-bomb dome became stronger. In the summer of 1966, Hiroshima City decided to preserve the A-bomb Dome, and a fundraising campaign to cover the necessary costs began. As a result, donations from within Japan and abroad poured in, the goal far surpassed. Hiroshima City commemorated completion of the preservation work by holding a “Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Exhibition,” in major cities including Tokyo, which were well received in all locations.

The success of the fundraising for the preservation of the A-bomb Dome and of the subsequent A-bomb exhibitions showed that presenting the facts of the atomic bombings could arouse public interest in the abolition of nuclear weapons. Since the late 1960s, apart from the preservation movement for the A-bomb Dome, there have been other efforts in Hiroshima to clarify the realities of the atomic bombing, and share and pass it on to society and future generations. Particularly, the map restoration project of the A-bombed areas elicited numerous testimonies about the realities of the bombing from citizens, and led to the formation of various citizens’ organizations with such objectives as praying for the repose of the A-bomb victims.

In 1975, NHK called for the citizens to draw and submit pictures of the atomic bombing to be kept for future generations, and many A-bomb survivors supported this project. They voluntarily drew pictures and wrote captions depicting their own experiences of the bombing. It is said that about 900 pictures in total were sent to NHK. These pictures were first displayed at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and have subsequently continued to play a role in communicating the realities of the atomic bombing in Japan and abroad.

(3) Restart of Schools and Peace Education

According to the Hiroshima Genbaku Sensaishi (Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster) (City of Hiroshima, 1971), 78 schools were damaged in the atomic bombing. Of them, 34 were either completely destroyed or had burned down, seven were completely destroyed, four had completely burned down, 20 were half-destroyed, and one was half-burned, leaving just 12 in usable condition. After the bombing, the majority of those schools were used as temporary relief stations for the injured, so for some time, it was impossible to conduct classes at schools.

However, the first action taken towards resuming classes was quick, and schools in Hiroshima City gradually resumed classes between September and November 1945. In fact, many children had lost their families and teachers were also suffered from the bombing, and there were, actually, very few students who attended the day schools reopened. Although schools were reopened, classrooms and teaching materials were practically nonexistent. Teachers brought their own materials, or had to use handmade teaching materials or those that were donated.

Japan was placed under the control of GHQ after the war ended, and it was made to shift from militarism to democracy. A new school system (six years of primary school, three years of junior high school and three years of senior high school system) was implemented in April 1947. In that year, the Fundamental Law of Education was enacted,and education based on the Coures of Study as the standard for curricula launched.

In September 1951, the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed. In the April of following year, 1952, the peace treaty went into effect and Japan recovered its sovereignty. Therewith, the occupation of Japan by GHQ ended. The restrictions on the freedom of speech was gradually eased around that time. For example, Genbaku no Ko; Hiroshima no Shonen Shojo no Uttae (Children of the A-bomb: Testament of the boys and girls of Hiroshima, Iwanami Shoten, 1951) , a collection of essays by children, was compiled to present their A-bomb experiences by Arata Osada, an A-bomb survivor and professor at Hiroshima University. After the Bikini Atoll Incident in March 1954, peace movements calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons spread throughout Japan. These movements also led to a peace movement initiated by children after Sadako Sasaki’s death, to pray for peace by folding paper cranes, and to establish a symbolic monument for children.

The academic abilities of Japanese children improved remarkably as a result of the educational policies introduced through the revisions in the Course of Study to promote the systematic approach of teaching. According to an international comparative study of scholastic abilities, Japan achieved higher rankings. After these survey results were published, education in Japan became a focus of international attention. It was believed that education was a factor that enabled Japan’s recovery from the tragedy of the war.

In 1969, the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha (A-bomb survivor) Teacher’s Association was established and teachers in Hiroshima began a movement promoting peace education. Initiatives focused on passing down A-bomb experiences took a firm hold in the 1970s, and peace education was stimulated nationwide by a movement to promote school trips to visit the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

(4) A-bomb Survivors’ Personal Perspectives on Peace

What are the A-bomb survivors’ perceptions of their A-bomb experiences in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and what messages do they want to pass down future generations? This section takes up the survey titled, “Questionnaire Survey: 60 Years after the Atomic Bombings” conducted by the Asahi Shimbun in 2005 and examines the survivors’ responses to the open-ended guestions to shed light on the survivors’ personal perspectives on peace, using statistical methods. The questionnaire targeted 38,061 people who possessed either the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificates or the Class 1 Health Check Certificates, and was conducted as a joint project with Hiroshima University.

First, the top 50 words that appeared most frequently in the experiences and messages written by 6,782 respondents are taken up. Words related to the recollections of their A-bomb experience can be mainly classified into two groups: (1) cluster of words describing the unforgettable hellish scenes from after the bombing, expressed with words such as “head,” “face,” “hands,” “burns,” “hospitals,” “corpses,” “water,” and “voices”, and (2) cluster of words expressing A-bomb experiences in relation to family members, such as “mother,” “father,” and “home.”

Words such as “world,” “peace,” “nuclear weapons,” and “nuclear” appear frequently in testimonies of A-bomb survivors. As pointed out earlier, it can be seen that the core element of the survivors’ perspectives on peace was “world peace” achieved through the “abolition of nuclear (weapons)” through the questionnaire. Based on their tragic A-bomb experiences, the survivors of the atomic bombings have gathered the core of their strong messages to protest against nuclear weapons.

The survivors’ perceptions of their atomic bombing experiences differ slightly by gender. Women tended to talk more about A-bomb experiences in relation to their family. The analysis of the testimonies shows that men had a stronger tendency to advocate for peace through the abolition of nuclear weapons, while women had a stronger tendency to call for peace, by calling for not only the abolition of nuclear weapons but also the absolute renunciation of war. This suggests perspectives on peace also differ by gender. Despite slight observable difference in messages according to gender, there were no significant differences seen according to location (Hiroshima or Nagasaki), age, or survivor category (according to how they were exposed to radiation). In other words, the survivors shared a common desire in their peace perspective, “world peace through the abolition of nuclear weapons.”

The “Questionnaire Survey: 60 Years after the Atomic Bombing” also asked the survivors what has supported them emotionally. According to answers received from respondents, the survivors’ physical and psychological trauma was alleviated by their families, communities and the peace movements. With these supports, they have tried to overcome their tragic experiences and have established their perspectives on peace, which is a world without nuclear weapons.

Inquiries about this page

Hiroshima Prefectural Office

Street address:10-52, Motomachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi, Hiroshima-ken, 730-8511

Tel:+81-(0)82-228-2111